photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

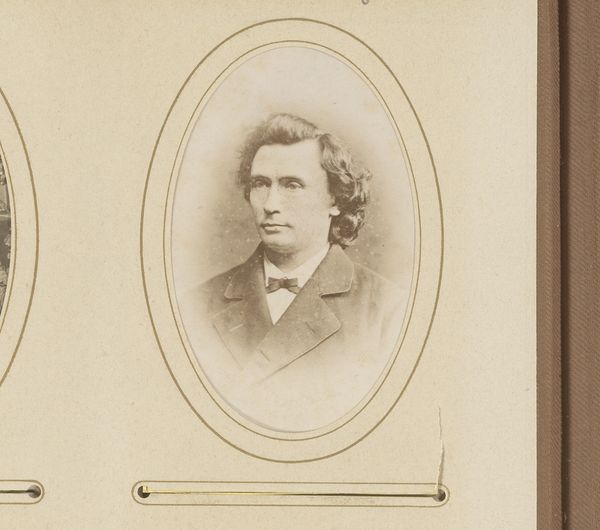

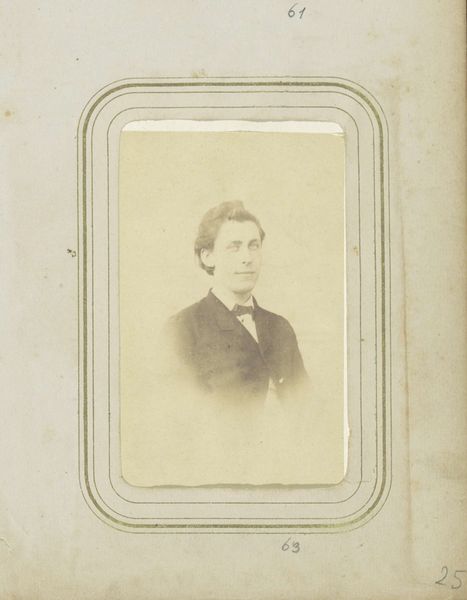

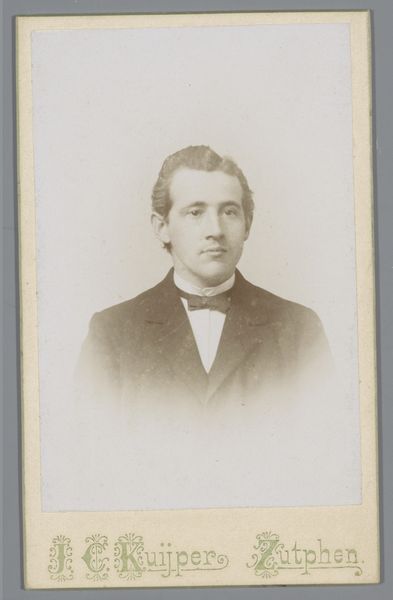

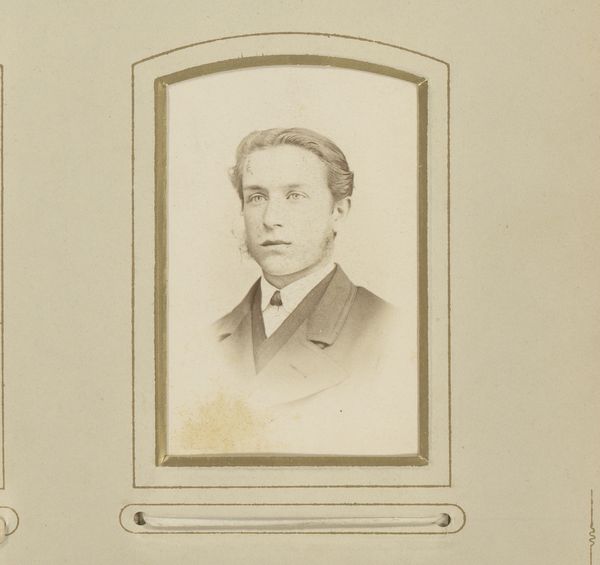

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have an albumen silver print simply titled "Portret van een man," or Portrait of a Man, created sometime between 1860 and 1885. The photograph's formal qualities – the oval frame, the sitter's serious expression, his formal attire – all seem so carefully posed and constructed. What do you see as being particularly important when interpreting a portrait like this? Curator: It's crucial to remember that early photography was heavily influenced by painting traditions. Consider the rise of the middle class in the 19th century and the increasing demand for portraiture. Photography offered a more accessible way to have one’s likeness preserved compared to commissioning a painting. It became a potent symbol of social status. How might the conventions used for painted portraits affect our reading of a photographic portrait like this one? Editor: That makes sense. The oval frame and formal pose definitely echo painted portraits of the time. I guess photography democratized portraiture, making it available to a broader segment of society, but was also shaped *by* that pre-existing tradition. It's fascinating to think about access and representation evolving together. Curator: Exactly. Early photographic portraits often adhered to strict aesthetic conventions to gain social acceptance as "art." Think about the sitter's clothing: It's not just about personal taste, but communicates profession, class, and aspirations. And notice how the subject directly engages with the camera - or *us*! That directed gaze makes it hard not to construct our own narrative about them. Do you find yourself making assumptions about this person's life and background? Editor: Definitely. His direct gaze does invite speculation. I am wondering if photographic studios promoted particular values and ideas of social aspiration, that even something seemingly individual, a portrait, played a role in that. Curator: Precisely! These images offer a glimpse into the past, but also reflect the societal values embedded within them, making them compelling documents of cultural history. Editor: That's really helped me think differently about how to approach portraits - seeing beyond just the individual in the image to broader cultural and historical contexts. Curator: And I'm reminded how accessible early photographs made portraiture as an art form, and what that said about societal changes and aspirations in the mid-19th Century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.