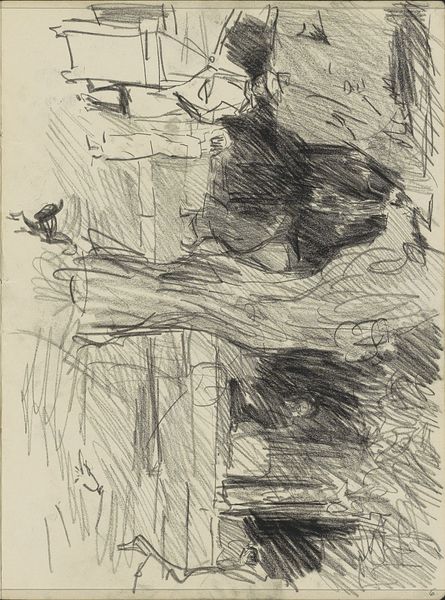

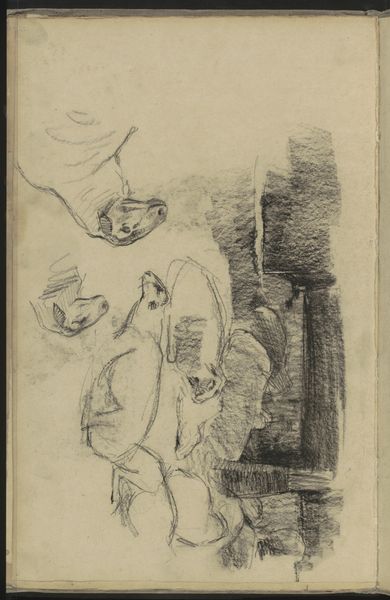

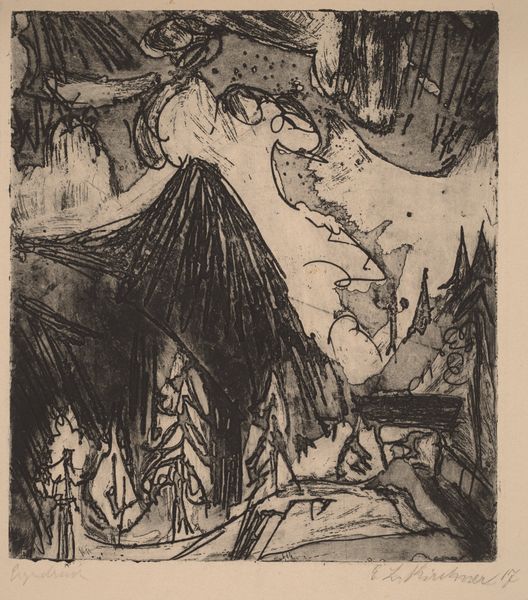

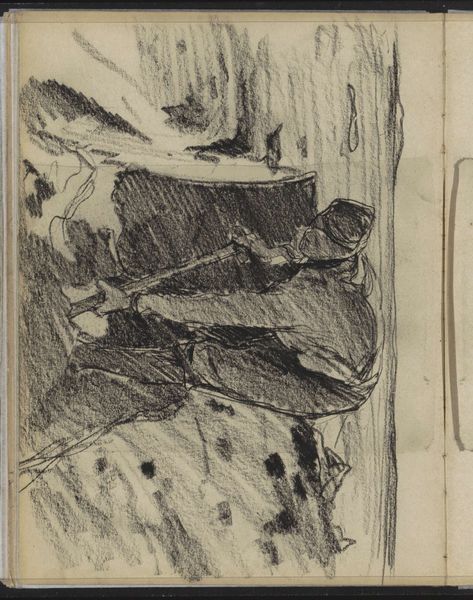

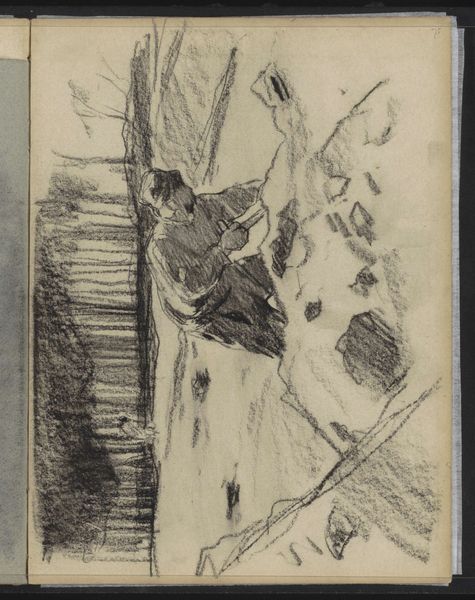

drawing, pencil, charcoal

#

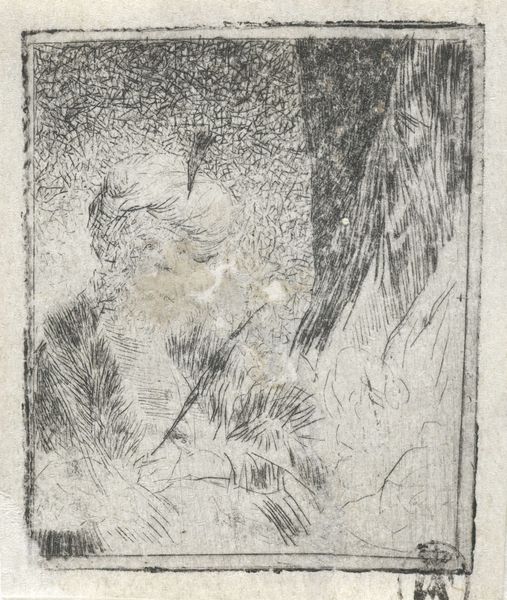

portrait

#

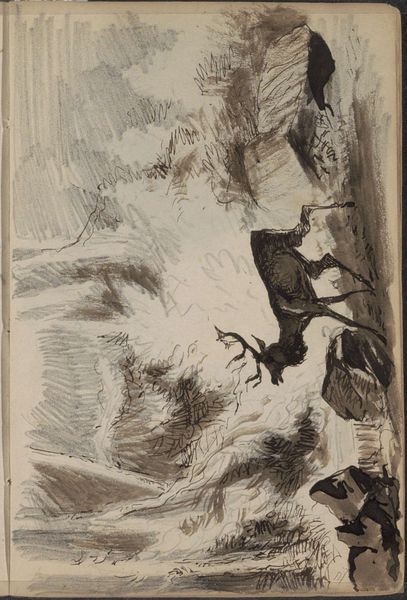

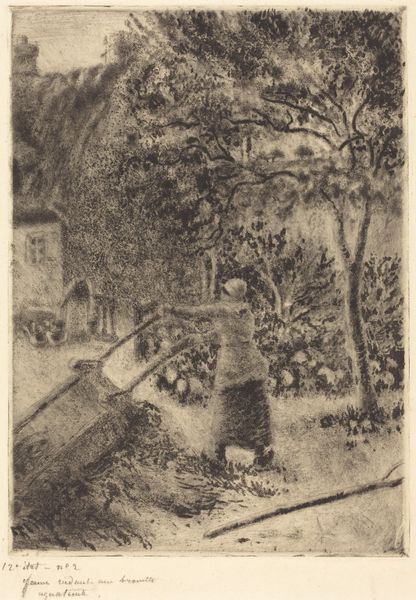

drawing

#

impressionism

#

pencil sketch

#

dog

#

pencil

#

charcoal

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a moody little drawing! Willem Witsen's "Etende boerenjongen," or "Eating Peasant Boy," made around 1887-1888. Look at those charcoal strokes. There's real energy there, a kind of…hunger, you know? Editor: Absolutely, the heavy use of charcoal and pencil lends a sense of urgency and social commentary. Witsen was part of a circle of Dutch artists interested in Realism, depicting everyday life, often with an emphasis on the working class and rural existence. What’s immediately striking is the subject’s vulnerability and the rawness of his lived experience. Curator: Right? It’s like a snapshot, catching him mid-meal. The shadows, the blurred lines… it feels so fleeting, almost voyeuristic. What do you make of the dog by his side? Editor: The dog is crucial. Often, such depictions serve to further emphasize the subject’s social standing, their dependency, and the realities of agricultural life. Think about how class is further marked through what is being eaten and its implied lack of access to resources. This wasn’t just about art for art's sake; it's an engagement with pressing social issues. Curator: It's fascinating to think of this as social commentary. I was just caught up in the sheer skill of the sketching—how he captures that sense of simple, repetitive consumption, of someone wholly immersed in the act. Editor: Yes, the technical skill serves a purpose beyond mere aesthetics. This piece places rural labor and working-class people in a field of vision typically dominated by bourgeois subjects, thus enacting its own kind of politics of representation. Curator: It almost makes me wonder what kind of world we might have if more of our everyday focus was drawn on…nourishment. Not only for ourselves, but everyone. Thanks for drawing out these themes, always helps to see further. Editor: Precisely! The act of viewing, the power of witnessing. Art can teach us to see not just images but worlds. This tiny glimpse into the 19th-century peasantry expands our present field of care.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.