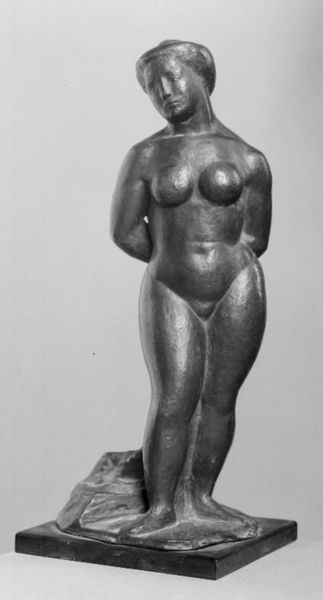

Dimensions: object: 737 x 152 x 152 mm

Copyright: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

Editor: So, this is Eric Gill's "Eve," a stone sculpture at the Tate. It feels…submissive? Almost ashamed. What's your take? Curator: It's interesting you pick up on that sense of shame. Gill was deeply religious and his work often grapples with the tension between sensuality and spirituality, particularly within the female form. Consider how ideas around female sexuality were policed during his lifetime, and how those power dynamics may be at play here. Editor: So, is this a commentary on the objectification of women, even in religious contexts? Curator: Precisely. Gill's personal life was complicated, even controversial. Can we separate the art from the artist here, and what does it tell us about the male gaze and its historical impact? Editor: That gives me a lot to think about – the sculpture as both a religious figure and a representation of societal pressures on women. Curator: Exactly. It's a potent reminder of the lasting influence of historical power dynamics on art and our understanding of it.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

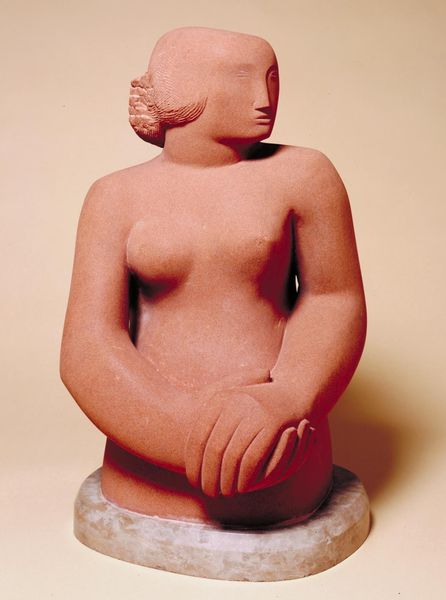

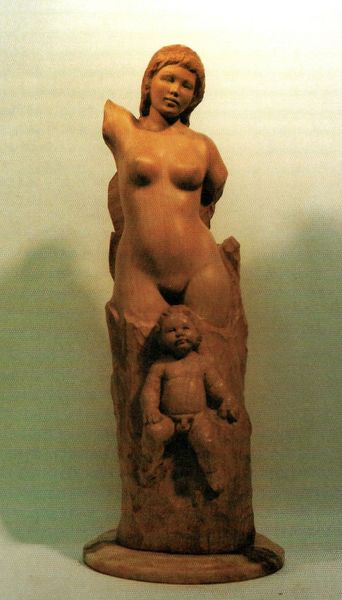

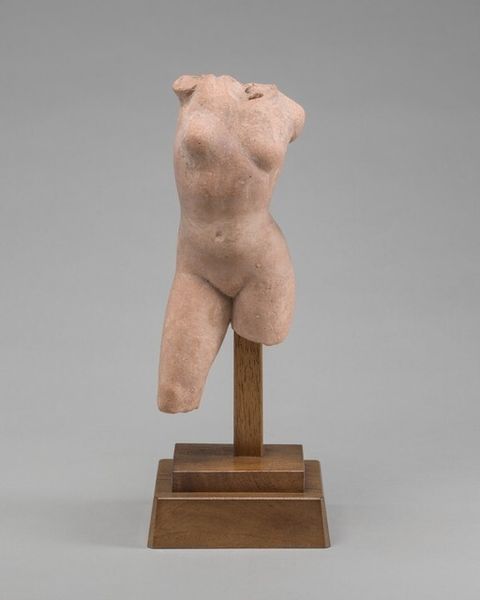

In the 1920s, the new critical approach of writers such as Roger Fry and R.H. Wilenski released a number of British sculptors from a slavish veneration of Greek art. They began to question classical standards of beauty by looking afresh at the art of non-European cultures. Eric Gill's interest in the art of non-European cultures developed before the 1920s, largely through the influence of the philosopher and theologian Ananda Coomaraswamy. In 1908 Coomaraswamy's lecture on Indian Art made a deep impression on Gill. In this sculpture Gill explores the relationship between the sacred and the profane, drawing in particular on traditional Indian sculpture. Gallery label, September 2004