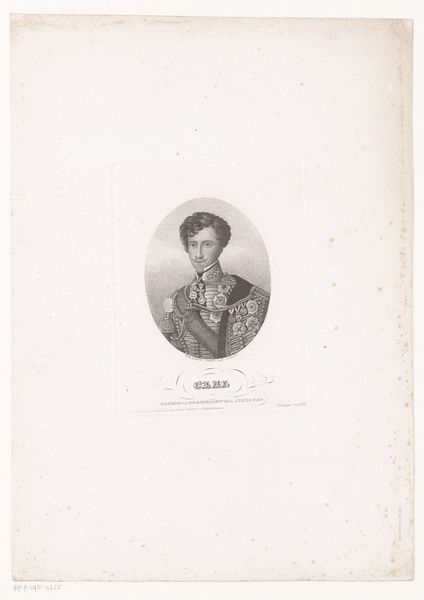

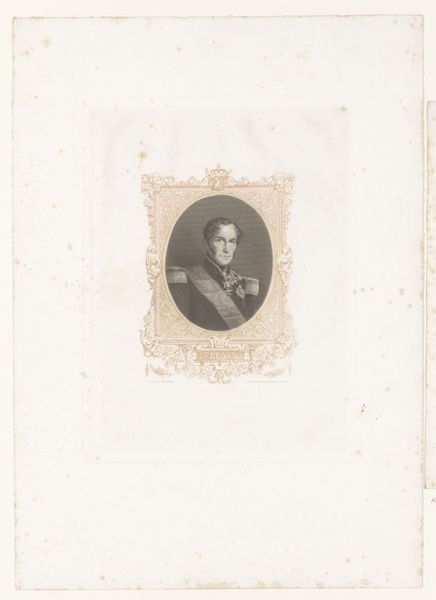

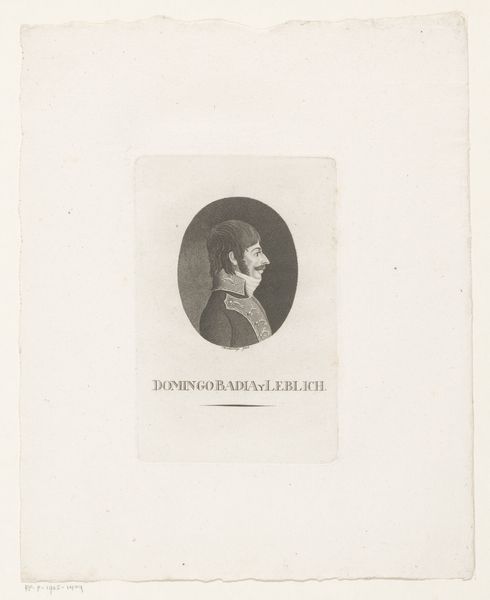

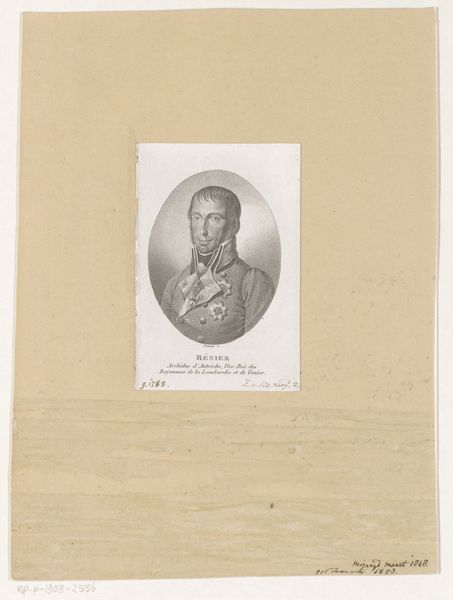

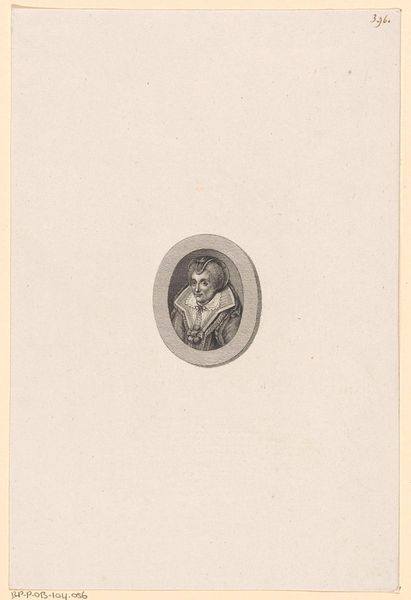

Portret van Jérôme Bonaparte, koning van Westfalen 1787 - 1828

0:00

0:00

ludwiggottliebportman

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

paper

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 105 mm, width 79 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At first glance, I'm struck by the meticulous detail rendered in what appears to be such a delicate medium. The overall effect is undeniably formal and controlled. Editor: Indeed. What you're seeing is Ludwig Gottlieb Portman's "Portrait of Jérôme Bonaparte, King of Westphalia," dating from between 1787 and 1828. It's a drawing, likely an engraving, on paper. Curator: An engraving! The precision is remarkable, particularly in the rendering of Bonaparte's uniform and decorations. Note the classical oval frame – it all reinforces a sense of aristocratic restraint and order, emblematic of Neoclassicism. Editor: It's fascinating to consider the labor involved in such an intricate work, especially given its apparent scale. The density of the marks speaks to a highly skilled hand, making repetitive, deliberate actions. We might even think about how this print was reproduced, what sort of social conditions afforded such detailed reproduction, and its availability to the public. Curator: I am more interested in the effect of light and shadow which sculpts Bonaparte's face, lending it a sculptural quality reminiscent of antique busts. There's a clear emphasis on idealized features, conveying power and authority through visual language. The choice to frame him in this classical manner seems significant. Editor: Perhaps, but think about how such an image, disseminated widely as an engraving, helped to manufacture a very specific kind of imperial power—one distributed through paper, ink, and, crucially, the labor of those reproducing it. How the act of making helps spread political ideologies, not just represent them. Curator: That being said, you can't dismiss the aesthetic success of the engraving itself. It functions as a potent symbol, its composition echoing ideals of leadership and decorum. Editor: True. Its historical significance is magnified by its materiality and circulation. To understand its full meaning, we have to see the drawing as a material object produced, distributed, and consumed within a specific context. Curator: Considering the constraints and the means employed, one appreciates the way in which the artist translated presence into an accessible, reproducible form. Editor: Exactly, and acknowledging the means also humanizes it, connecting it to real processes of work and economy beyond pure representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.