#

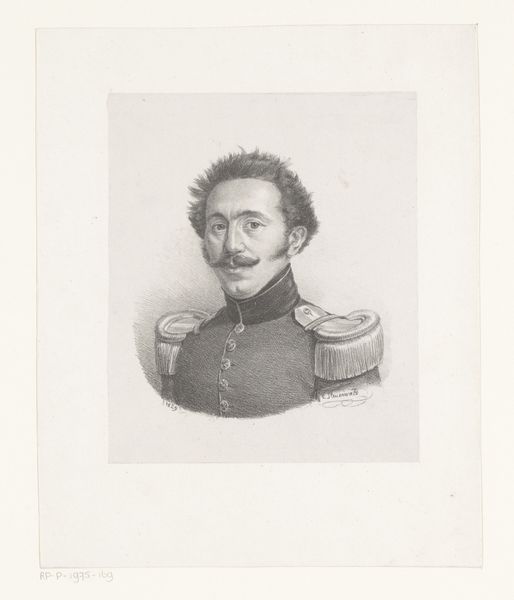

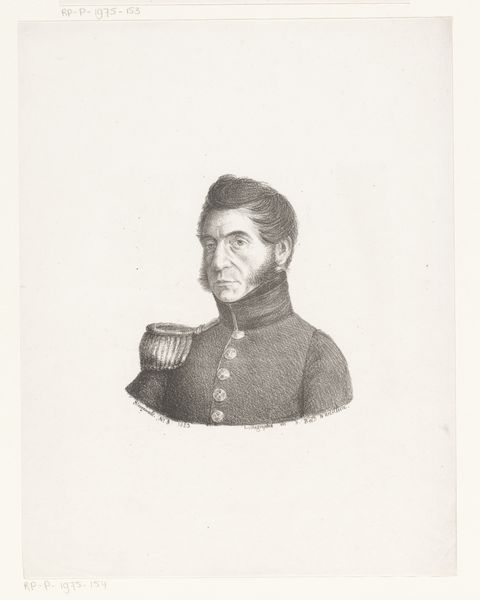

pencil drawn

#

light pencil work

#

photo restoration

#

pencil sketch

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

yellow element

#

limited contrast and shading

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

Dimensions: height 234 mm, width 198 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a lithograph from 1823, titled "Portret van onbekende militair," or "Portrait of an Unknown Soldier" by Christian Heinrich Gottlieb Steuerwald. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: I’m immediately struck by the economy of line. Steuerwald achieved such a strong likeness with what looks like fairly light pencil work, all cool greys and stark paper. It evokes a certain austerity, don't you think? Curator: Yes, the austerity mirrors the period's emphasis on military stoicism. These were turbulent times in Europe; the Napoleonic wars had just ended, and many nations were redefining themselves, often through military strength. This portrait likely served as a form of national pride and stoic leadership, embodying those values. Editor: Absolutely, and the way the artist renders the uniform—crisp collar, precisely placed buttons—suggests a formality designed to project authority. Though the limited contrast adds to the seriousness; less dynamic, more pensive. Curator: Precisely. The very act of creating portraits like this cemented the military's place in society. It presented an idealized image to the public, a symbol to rally around and to encourage potential recruits, subtly reinforcing power structures. Editor: The shading around his eyes gives the impression of tiredness, though; or perhaps simply serious reflection? The subject is not gloriously valorous, necessarily; Steuerwald grants him a touch of interiority. Curator: Interesting, that touch of interiority possibly opens a wider social dialogue too. It acknowledges the personal burdens of military service even while celebrating the institution itself. It might invite different, more sympathetic readings of soldiery beyond merely strength. Editor: This visual analysis, combined with understanding the era, offers rich insights into the society of the early 19th century. I see it now, not just a portrait, but a social and historical document rendered through line and tone. Curator: Indeed, observing art is only the first step in uncovering these deeper contextual narratives that artworks are products of and also contribute to shaping our world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.