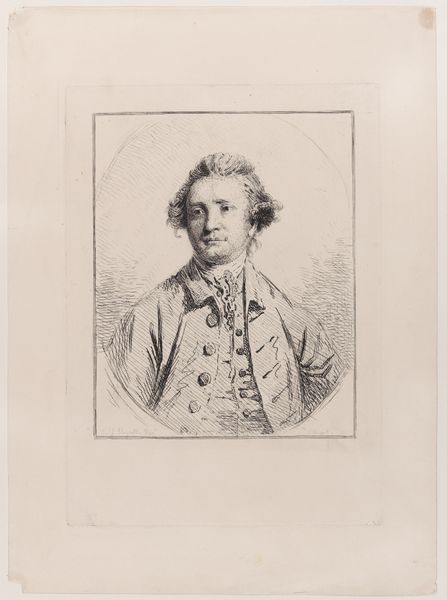

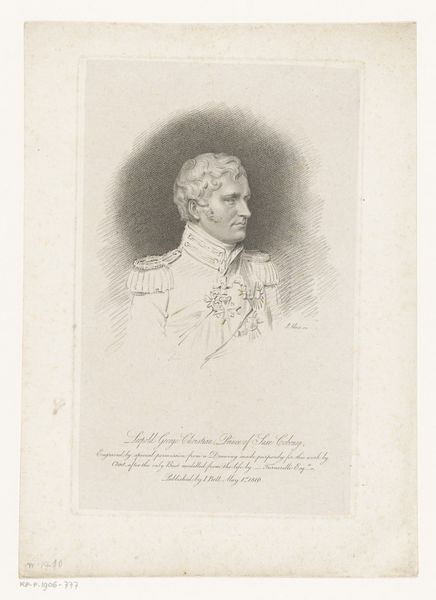

drawing, print, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

realism

Dimensions: sheet: 8 9/16 x 5 3/8 in. (21.8 x 13.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This pencil drawing depicts Brigadier General John Glover, made sometime between 1820 and 1880, attributed to Henry Bryan Hall. The piece resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first thought is of how fragile it feels. The soft gradations of the pencil create an almost ghostly presence. It really conveys a sense of someone slipping out of memory. Curator: That's interesting, because portraiture of this kind often sought to immortalize the sitter, especially military figures like Glover. He was, after all, a significant figure in the Revolutionary War. Editor: But consider the choice of material, pencil, or perhaps charcoal. So accessible, so ubiquitous. Was this meant to be a study for something grander, maybe an engraving? Or is the medium itself part of the statement? What does this suggest about its means of circulation? Was it meant for personal display? Curator: Hall was indeed an engraver. So, a print made from this drawing likely made this portrait widely accessible to a growing American middle class keen to connect with their revolutionary heroes. Consider the politics of image production in this era. Editor: And what labor went into creating it? A drawing like this may seem quick, but countless hours of honing a skill are embedded within those pencil strokes. What were Hall's working conditions like? Were they akin to mass production or an artisan craft? The materials betray a sense of volume in production, don’t they? Curator: Precisely. It touches upon a shift from unique artworks to reproducible images in a rapidly industrializing society, and their effect on national consciousness. It allowed people from various socioeconomic backgrounds to connect with this specific image of Glover, creating a unified idea of a founding father. Editor: It’s a delicate balance. What might seem like a straightforward, perhaps even mundane, portrait becomes an intricate web of material realities, labor, and social exchange. That’s what makes it interesting. Curator: Yes, it is in part through exploring art’s public role, particularly in early American identity formation, that its true value is unlocked. Editor: Indeed, by understanding the historical, and especially the material conditions that enabled the piece we move towards understanding that time more comprehensively.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.