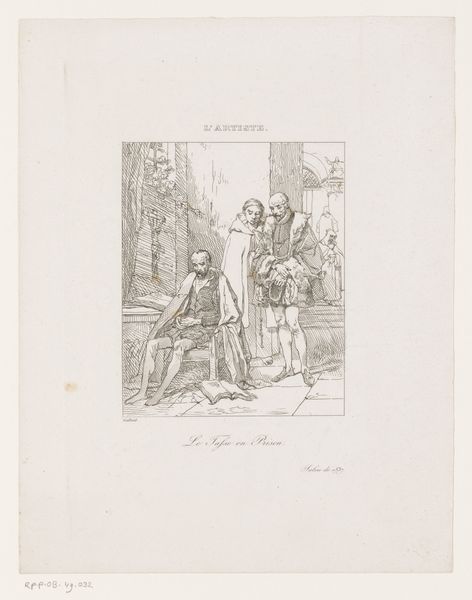

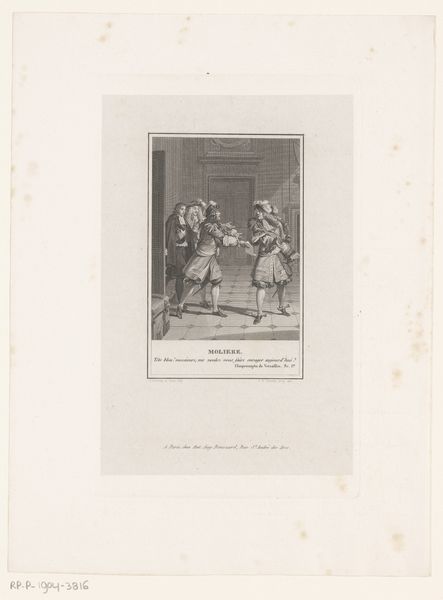

print, etching, paper, ink

#

narrative-art

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

Dimensions: height 362 mm, width 267 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

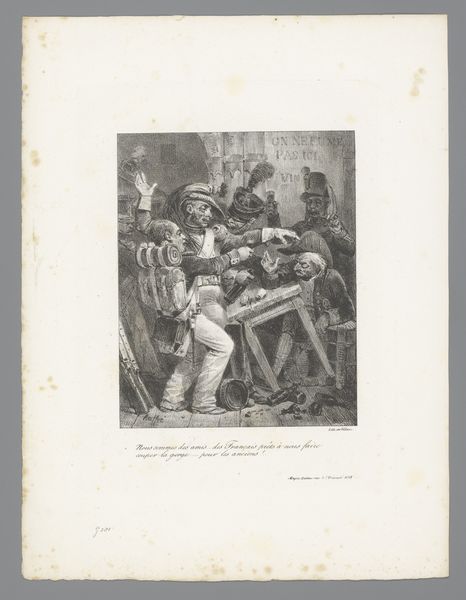

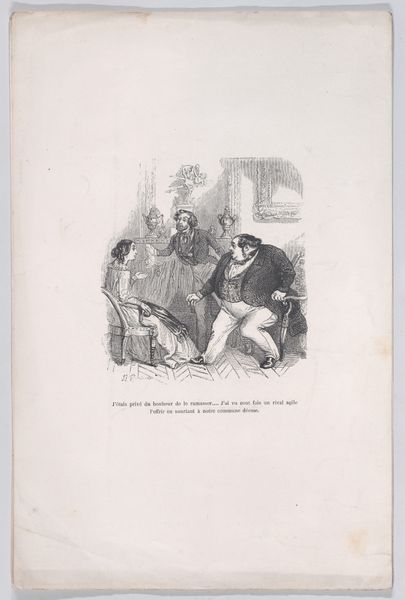

Curator: Here we have an etching by Auguste Raffet, dating back to 1827, entitled “Man ondersteunt andere man, links man onder een tafel,” which translates to "Man supports another man, left man under a table." Editor: My immediate impression is one of disquiet, of instability. The composition, the stark ink lines – it evokes a feeling of social upheaval, wouldn't you agree? Curator: Indeed, and it's important to consider the political backdrop. The post-Napoleonic era was one of social tension and evolving power structures, especially with the rise of the Bourgeoisie. How would that inform a work like this? Editor: Crucially! Raffet, as a Romantic artist, would've been engaging with contemporary issues. The fallen man under the table could symbolize the defeated old guard, perhaps even critiquing notions of traditional hierarchy, and highlighting class struggles. His dejected presence amplifies questions about marginalized peoples. Curator: The other figure assisting the disoriented individual offers a complex narrative of dependency and perhaps, veiled derision. It certainly complicates readings of male power dynamics within societal shifts. Note the artist's careful depiction of clothing too, a real signifier here! Editor: Clothing, yes, the differences in dress indicating differing social strata and perhaps attitudes toward the intoxicated. But beyond that, I am interested in how we see male vulnerability depicted and disseminated, what this does for notions of gender identity at that moment in time? Curator: Very pertinent points. Etchings like this, in their wide circulation, shaped public opinion and fueled political discourse through very specific depictions of societal ills or societal commentary. The print served as a powerful form of social critique accessible to many. Editor: It prompts us to think about the relationship between art and public perception in the rapidly changing world of 19th century France and the dissemination of these prints and its importance for political action. So much hidden, right? Curator: It does invite layers of critical thinking; seeing echoes even today! Editor: It remains quite the poignant conversation piece, doesn’t it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.