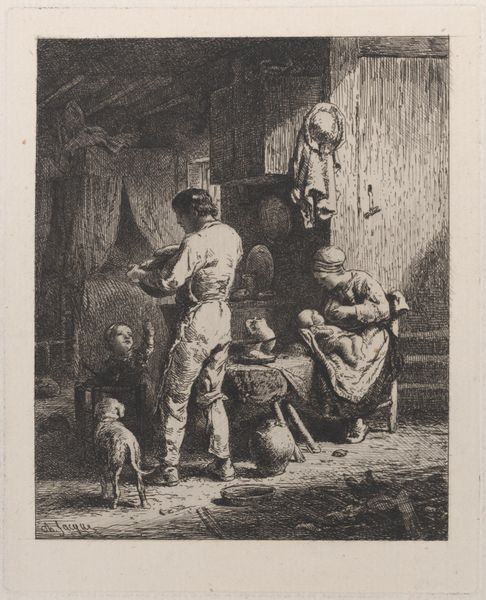

drawing, print, etching

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

realism

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 7 3/16 × 9 15/16 in. (18.3 × 25.3 cm) Plate: 2 7/8 × 5 5/8 in. (7.3 × 14.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

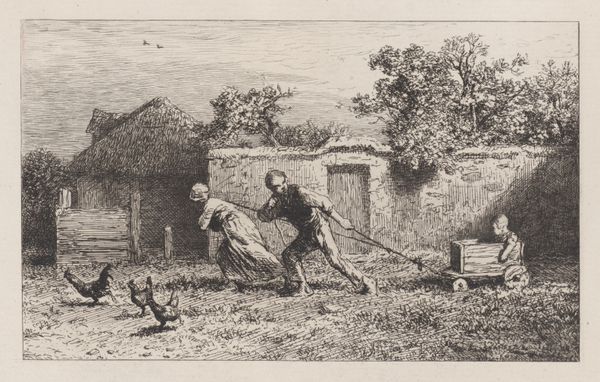

Curator: Charles Jacque's etching, "Washer Woman," from 1845, presents a scene of daily life in what appears to be a working-class neighborhood. It’s currently held here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first thought is the sheer weight of the woman’s labor. You can almost feel the heft of the water-soaked laundry she’s about to tackle. There's an oppressive atmosphere conveyed by the close quarters and the visible signs of poverty. Curator: It’s significant to consider the context of genre painting during this era. Jacque, like many of his contemporaries, found artistic merit in depicting the lives of ordinary people. The image subtly challenges the romanticized depictions of rural life so prevalent at the time, and perhaps shines a light on a kind of labor generally performed by women. Editor: Absolutely. We have to think about whose stories get told, and by whom. This woman isn't idealized; she’s captured in a moment of strenuous activity. And let’s not ignore the children in the background. This etching gives us insight into the economic and social structure of 19th-century labor where childhood is spent on the margins of adult labor. Curator: Indeed. Looking closely, we see how Jacque uses the etching technique to create intricate details—the texture of the woman's clothing, the rough-hewn wood of the buildings, and the messy accumulation of tools. There's a strong sense of realism. It isn’t glorifying hardship, but capturing a slice of lived experience. Editor: I find myself thinking about the absent male figure, who’s most likely performing his own strenuous job. How do race and class affect not only the subject’s relationship to her family, but the relationship with this viewer looking into a specific kind of poverty? This image sparks these broader dialogues. Curator: Precisely. And considering how art institutions often focus on privileged narratives, this etching acts as a poignant reminder of the myriad untold histories that shape our understanding of the past. Editor: I’m grateful for art like this—that prompts necessary interrogations of how power and visibility intersect, particularly around gender and labor. Curator: For me, seeing this artwork really enhances my understanding of 19th century social life and how this period is framed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.