#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

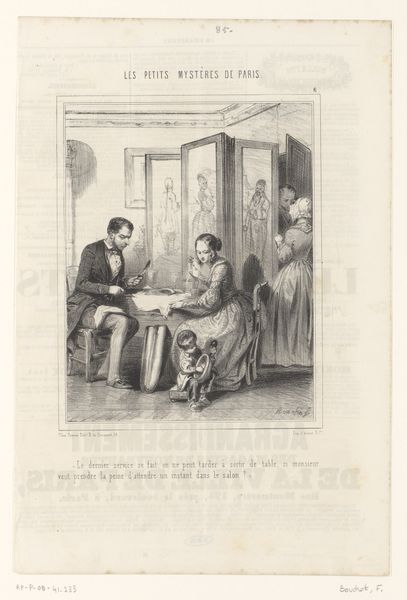

quirky sketch

#

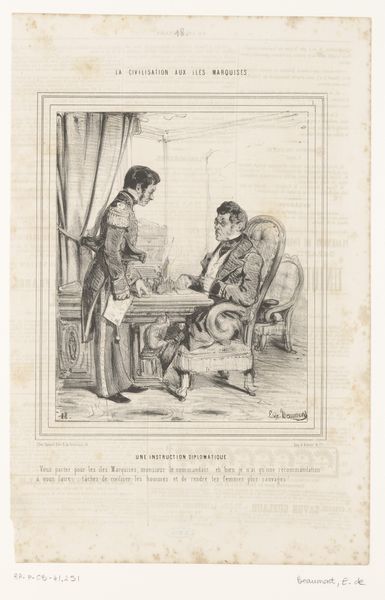

old engraving style

#

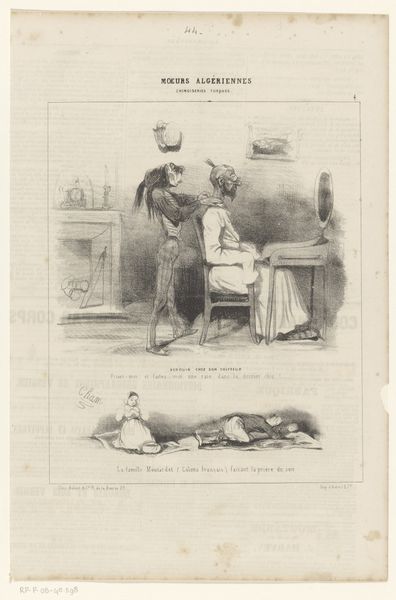

personal sketchbook

#

old-timey

#

sketchbook drawing

#

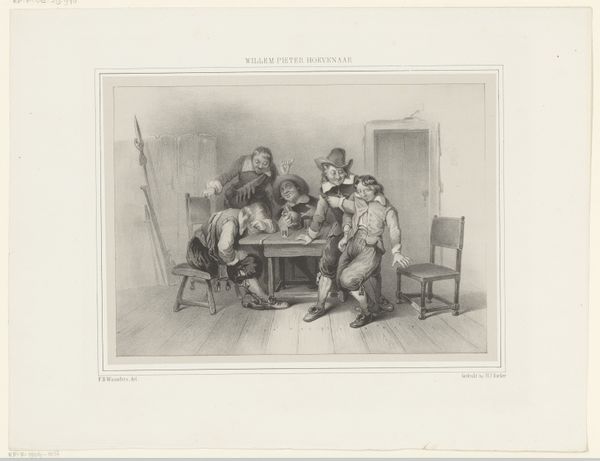

watercolour illustration

#

sketchbook art

#

watercolor

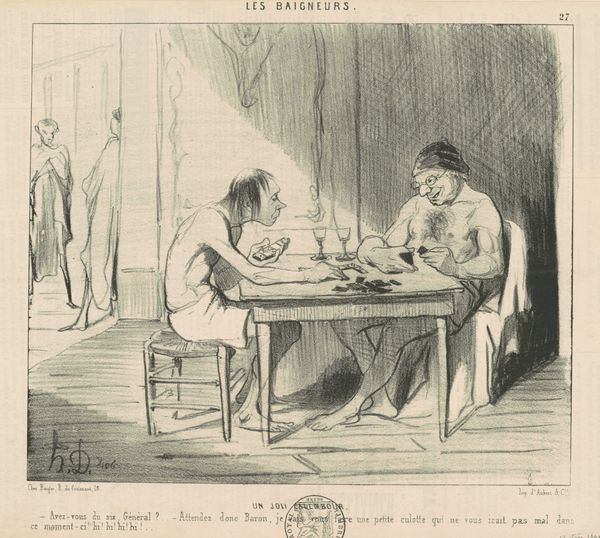

Dimensions: height 363 mm, width 238 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

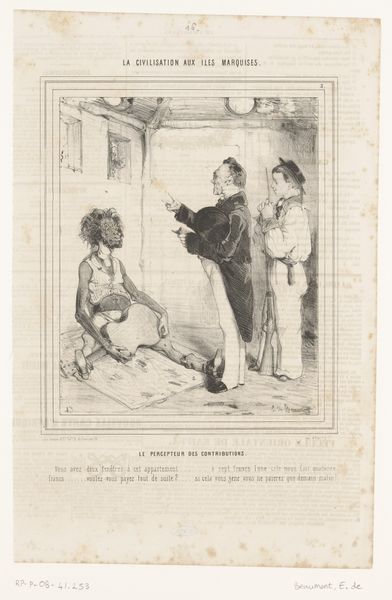

Curator: Isn't there something so profoundly melancholy about this 1843 watercolor by Edouard de Beaumont, titled "Karikatuur van twee dominospelende mannen"? It lives at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Melancholy? It feels more like a snapshot of colonial-era industry. Look at the setting, the cramped quarters; it suggests a temporary shelter, a place of labor. And the men themselves, their roles defined not by leisure but by the material conditions of their existence, with their skin colors heavily represented. Curator: Yes, the racial aspect cannot be ignored. But look at the way de Beaumont renders their faces – the resigned smoker, the intently focused player, even the onlooker with a flicker of something… pity? The materials serve the expression. The aged, toned paper seems to seep into the scene, a wash of time and inevitability. It reminds me of old family albums, the weight of inherited history. Editor: I’m more struck by what the artist leaves out. We see no tools, no obvious signs of labor beyond these three men enclosed within a stark structure, what does that imply about production here? Is dominoes a way to make use of idle labor? It isn’t about high art, I don’t think. De Beaumont seems fascinated by documenting process; it isn't pure artistic exploration, or we would see brush strokes with different densities to create tonality, not simple washes. The lines around their clothes are simple and clear and they are merely there as placeholders to present a body that is hard at work, but where the production lies isn't clear. The watercolor functions almost as an anthropological study. Curator: An anthropological study with a touch of heartbreak, perhaps? I find the intimacy of the scene unsettling, knowing the power dynamics at play. It feels almost voyeuristic, catching them in this shared moment of… what, exactly? Boredom? Complicity? Resignation? And those suggestive lines… that little bag… could that be about to open us into another perspective entirely? Editor: Right, which also reflects back on Beaumont and the role he had at the time, observing them so plainly. One could not detach this art from its roots when contemplating colonial times. Look at their very hands and arms that were responsible for untold material labor! I am sure Beaumont's vision was never just about melancholy but capturing an ethos in order to relay information. Curator: Perhaps. I still sense a deep well of… yearning. Perhaps yearning for a world where this scene isn't so heavy, so freighted with implication. In a time before photography, perhaps drawing someone was about understanding and acknowledging the differences. And at a more human level, this scene transcends its historical moment. What have you made of it? Editor: We need to keep in mind that the value isn’t simply the surface-level emotion—but is in all that it reveals about the conditions of colonial society and that time period as the product of colonial systems that defined life then. The process reflects on so many processes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.