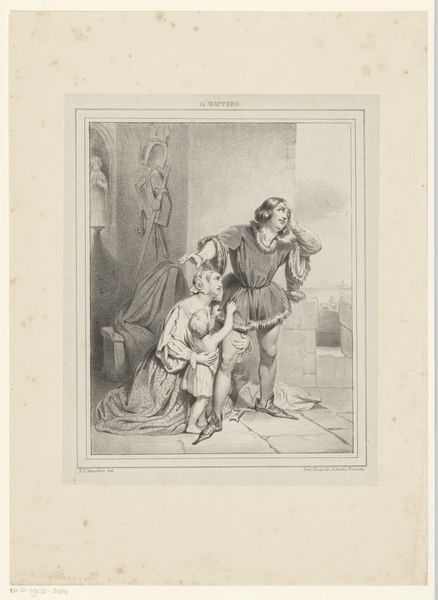

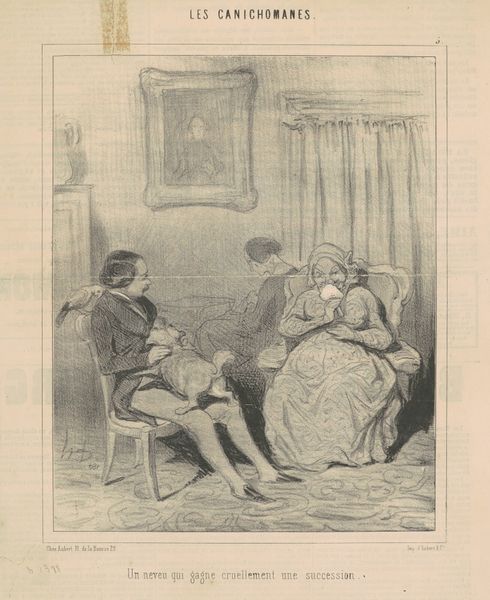

Karikatuur van een man die de maanden tussen zijn trouwdatum en de geboorte van zijn kind telt 1838 - 1840

0:00

0:00

fredericbouchot

Rijksmuseum

drawing, lithograph, pen

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

lithograph

#

caricature

#

romanticism

#

19th century

#

pen

#

pencil work

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 363 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

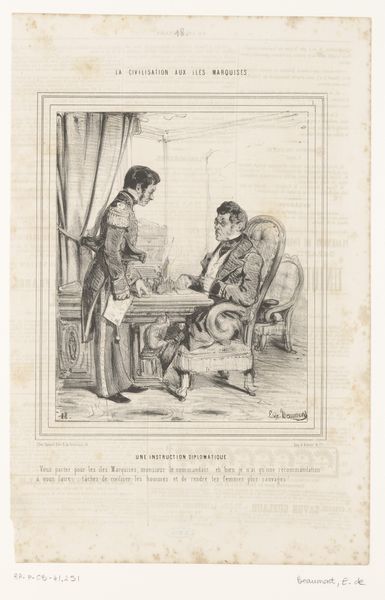

Editor: Here we have Bouchot's lithograph from around 1838, "Caricature of a man counting the months between his wedding and the birth of his child". There's a clear tension between the anxious husband and what I presume is the midwife with the newborn. What do you see happening in terms of the larger cultural landscape being critiqued? Curator: What strikes me is how this piece uses a relatively accessible medium like lithography to comment on social anxieties surrounding marriage, procreation, and the economic realities of family life in 19th-century France. The exaggerated features of the figures, particularly the man’s worried expression and the woman's laboring pose, are rendered through pen and ink in a mass-producible format. This inherently democratizes the commentary. How does the materiality inform your interpretation? Editor: It's interesting to consider that it's a lithograph - more accessible to the masses and also implies more labor for production. Curator: Exactly! Think about the workshops producing these images, the labor involved in creating the stones for printing, the distribution networks. It reflects a changing society, one where print culture is shaping social discourse and family expectations. What societal pressures might be subtly embedded within such a piece? Editor: The commentary definitely portrays some unease surrounding marriage. Are we talking about pre-marital relations or the quick-turnaround being negatively highlighted through production means? Curator: Precisely! By foregrounding the anxiety of this father, created through the technical reproducibility of the lithograph and therefore highlighting consumption and affordability, Bouchot isn’t merely telling a joke. He's subtly pointing to a period when familial ideals were being reshaped. Editor: I see. So it's less about individual moral failings and more about a systemic critique mirrored by the methods of artistic production. I hadn't thought about it that way. Thanks. Curator: Glad I could shed some light!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.