drawing

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

incomplete sketchy

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

initial sketch

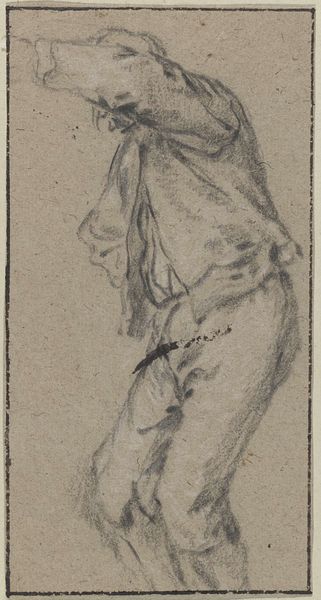

Dimensions: sheet: 21.2 × 12.4 cm (8 3/8 × 4 7/8 in.) framed: 39.37 × 31.75 cm (15 1/2 × 12 1/2 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Strozzi's "A Standing Man with Cloak and Gloves," dating back to the 1630s, immediately gives me the sense of a fleeting observation captured in ink on toned paper. Editor: Yes, there’s a rawness that really appeals. I’m interested in the red chalk, which wasn't just a readily available material, but became crucial for life drawing. The immediacy hints this was probably an atelier study, a preparation. Do we know anything about the paper itself? Its manufacturing would have a story. Curator: The paper’s toning does contribute a lot. It seems deliberately chosen – perhaps he aimed for a specific warmth or aged quality for contrast against the red chalk? As a rough sketch, its goal was very likely pedagogical, helping young artists understand human anatomy and the play of fabric. It suggests Strozzi was actively involved in transmitting knowledge through material engagement. Editor: It’s interesting to consider the social function of a piece like this within an art workshop, it might offer insight into the economic realities of art production at the time. What value did such sketches hold outside the studio, beyond its purpose as instruction for upcoming artists? Curator: Exactly. Consider the socio-economic structure of artistic training: the apprentices, the commissions… each hasty mark hints at an extensive material culture supporting it all. The sketch's imperfection points at what’s considered 'artistic merit'. We often assign value to something appearing effortless, but ignore the labor behind it. Editor: True. And its incomplete, sketchy quality emphasizes a sense of ‘behind the scenes’. These kinds of materials can invite an interesting discourse regarding artistic intent. Maybe its public value was to act as sort of proof of artistic dedication; that it was more than a mere craft, as something inherently imbued with genius. Curator: Indeed. Looking closely at the laid lines of the paper as a fundamental, material component brings us much closer to considering those social, economic, and aesthetic dimensions shaping even the most unassuming artworks. Editor: Thanks; considering this society portrait's place in art history makes me more sympathetic to seeing it within those systems of patronage and workshop structure. It becomes more alive by knowing something about that lost labor.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.