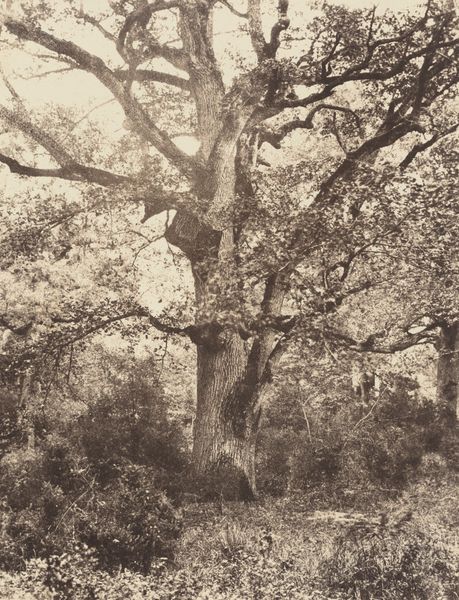

Dimensions: Image: 23.1 x 33 cm (9 1/8 x 13 in.) Mount: 44.8 x 59.5 cm (17 5/8 x 23 7/16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

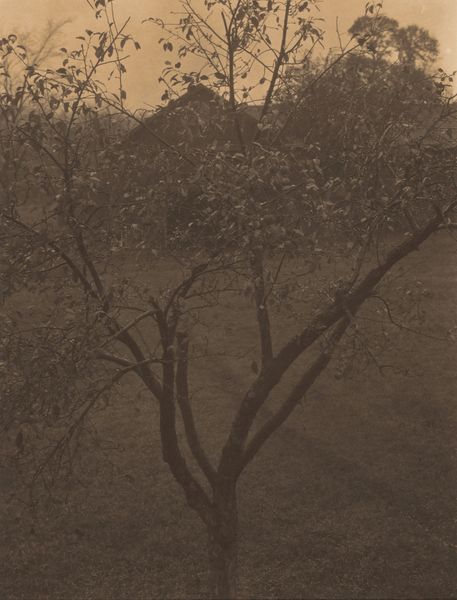

Curator: Auguste Salzmann’s “Jerusalem, Chemin de Naplouse,” created between 1854 and 1859, offers us a view framed by ancient trees and a distant wall. Editor: There’s a starkness here, almost like an etching. The monochromatic tones and barren ground evoke a sense of austere beauty. It feels heavy, in a way. What process did Salzmann employ? Curator: He created this using the gelatin-silver print process, which allowed for remarkable detail and tonal range. Saltsmann's work was intended as an "archaeological" tool. He wanted to provide a document of biblical lands through this new medium of photography. Editor: So the medium is the message? The new medium becomes the trusted record? It's interesting that something we perceive as romantic imagery was produced using an industrial chemical process that allows mass distribution. How did that context influence the way Salzmann worked, I wonder? The flat ground looks worked, and not at all like the site of an imagined Romantic Eden. Curator: Well, photography held a different cultural position then. The romantic lens through which Salzmann viewed the scene speaks to an idealization of the Holy Land, an Orientalist desire for a connection to ancient history, and he was supported by the powerful Revue de l'architecture. He’s carefully positioned these gnarled trees, not just as specimens, but as witnesses to history. He received a commission from the archeologist Albert de Luynes to create a set of prints. This adds an interesting wrinkle into his creative practice and freedom. Editor: So he’s negotiating material reality – that dusty, stony ground, the work of the land-- and aestheticized historical concepts to sell an image to a specific elite audience. Was the "archaeological" detail useful for a colonial or proselytizing project at this time, I wonder? That sky looks artificially bleached, doesn't it? Curator: Precisely. This image offers a potent reminder of the ways photographic representation shapes our understanding of place and history, enmeshed with contemporary cultural power structures. Editor: So much more than just a pretty landscape, then. Curator: Absolutely. I find the combination of historical context and photographic materiality really deepens its significance. Editor: Agreed. Seeing that stark landscape shaped by specific socio-political interests has changed my perception of what I at first thought was simply an old photograph.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.