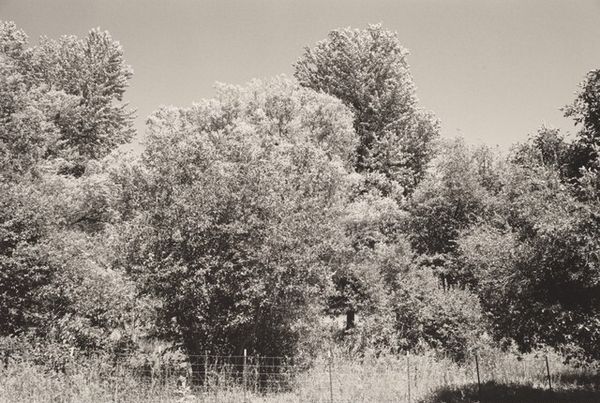

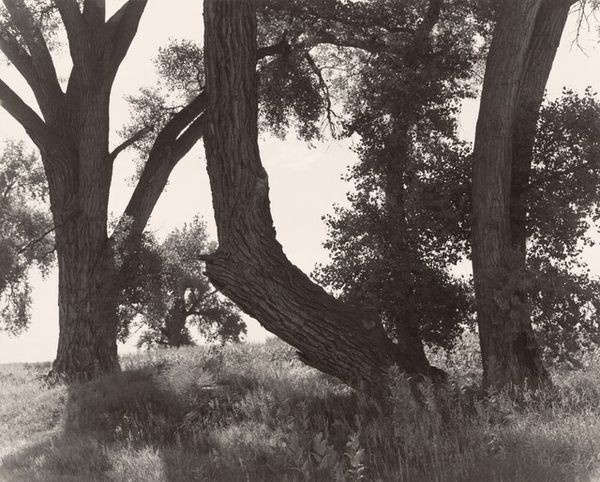

Windbreak on a farm being destroyed for development, Longmont, Colorado 1982

0:00

0:00

#

natural shape and form

#

black and white photography

#

countryside

#

black and white format

#

outdoor scenery

#

low atmospheric-weather contrast

#

black and white

#

monochrome photography

#

monochrome

#

shadow overcast

Dimensions: image: 37.9 × 47.4 cm (14 15/16 × 18 11/16 in.) sheet: 40.3 × 50.4 cm (15 7/8 × 19 13/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

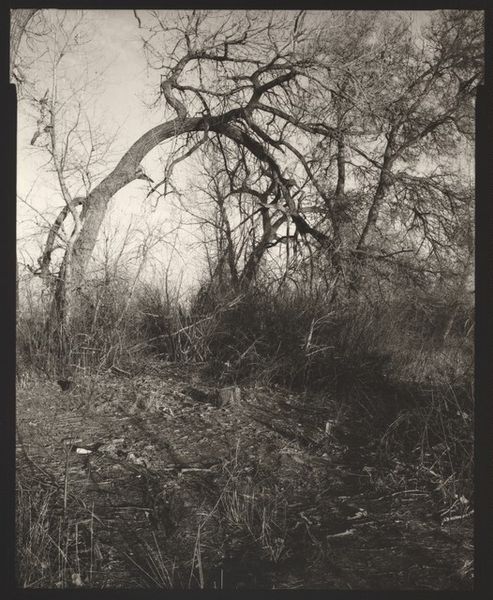

Curator: Here we have Robert Adams' "Windbreak on a farm being destroyed for development, Longmont, Colorado," from 1982. What strikes you about this piece? Editor: There’s a melancholy stillness about it. A kind of raw, quiet grief seems to emanate from those bare trees. Curator: It’s powerful, isn't it? Adams was deeply invested in documenting the changing landscape of the American West. This is a silver gelatin print; we can consider how that materiality and the choice of monochrome impacts the narrative. Editor: Black and white immediately infuses a sense of timelessness and solemnity. The windbreak, those trees, stand as silent witnesses. Windbreaks often symbolize shelter, protection—but what happens when that symbol is itself under threat? Curator: Precisely. The materiality speaks volumes here. Think about the chemical processes involved in developing the print, reflecting the industrial forces reshaping the land. The labor inherent in traditional photography becomes a critical comment on the displacement caused by other labor, other construction. Editor: The very shape of those trees also hints at a deeper symbolism. They’re contorted, reaching, almost pleading against a seemingly indifferent sky. They speak of resilience and loss. Is the windbreak becoming a funerary marker? Curator: That resonates, given Adams’ larger body of work focusing on suburban sprawl and environmental concerns. It’s fascinating to examine this in terms of consumption. These photographs were sold and purchased, making them objects in the market—and participants, however passively, in the very system Adams critiques. Editor: So the image itself, through its dissemination, contributes to the cycles of commodification and destruction that it seems to lament? It reminds me of ancient myths of doomed groves and sacred spaces, places where nature's memory clashes with human ambition. The farm and its windbreak becomes like the final stronghold. Curator: Absolutely. And as we reflect, let's remember that art and material culture constantly evolve as our world does. It serves as a historical record and a testament to human choices. Editor: And the artist allows these stories of loss and transformation to be told by the earth itself through evocative signs and shapes. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.