drawing, oil-paint, paper, ink, pencil, chalk, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

high-renaissance

#

narrative-art

#

oil-paint

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

oil painting

#

ink

#

child

#

pencil

#

chalk

#

watercolour illustration

#

charcoal

#

italian-renaissance

Copyright: Public Domain

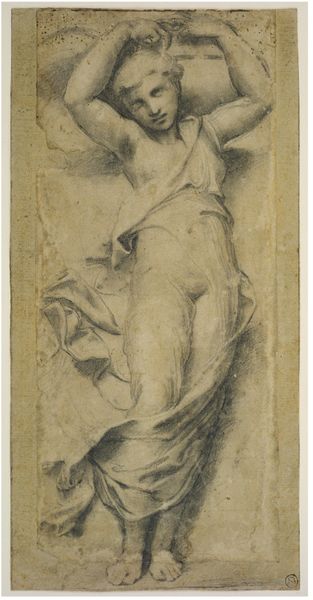

Curator: This is Parmigianino's "Study of the Madonna and Child," believed to have been created between 1526 and 1530. It's a fascinating drawing currently residing at the Städel Museum. Editor: The delicacy is astonishing. Looking at it, the initial feel is of such quietude—a whispered secret between mother and child. But the clouds below…they’re more like scaffolding. Curator: That's a really interesting way to put it. Let’s dive a bit into the "making" of this artwork. As a drawing, likely rendered in chalk, maybe touched by ink, it's preparatory. You can see the visible layering; Parmigianino builds form through repetition. Consider what’s at stake when you sketch: paper availability, quality of tools, studio labor… Editor: Right. I mean, he's really working to find the form, the weight... You can practically see him experimenting. The Madonna’s face—it's almost mournful, yet undeniably beautiful. There's a definite tension there that feels particularly potent. And given its Renaissance roots, that interplay with both divine love and human complexity just enriches it, you know? Curator: Exactly. We see High Renaissance idealism bumping into something more searching. The materiality offers clues to the thought process. How the charcoal, the paper grain... these textures carry their own histories, separate from subject and artist intention. It’s like they add their own, often ignored, voices to the conversation. Editor: I also keep coming back to those hands! Both the Madonna's and the child's... the tenderness with which they seem to be almost interwoven is almost disarming. Did he rework them many times do you think? I am looking closer and there’s a definite presence—almost a character—within them! Curator: Absolutely; notice how Parmigianino's process becomes our window. Chalk dust scattered just so, now a kind of spectral haze after half a millennia... How the paper support survives after so many curious eyes and traveling exhibitions... To reflect, it isn’t a singular object—it's an ever-shifting accumulation of its journey and means. Editor: Well, thinking about how the labor and supplies are wrapped up in it really pulls it away from some dusty artifact; that’s nice food for thought.

Comments

stadelmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

This 'Study of the Madonna' came from the collection of the founder of the Städel Institute, Johann Friedrich Städel (1728-1816), who owned several drawings by Parmigianino. The Italian painter, whom Giorgio Vasari, the artists' biographer during the Italian Renaissance, described as the "heir to Raphael's soul", was highly regarded during the eighteenth century. The reason for this may be that his elegantly Mannerist art demonstrates a certain proximity to the lightness of the Rococo, but it is also certainly due to Parmigianino's virtuosity in drawing, which had always been universally praised. The sensitive medium of drawing played a special role in the era of enlightenment and sensibility.In the brush drawing, which is based on a light sketch in black chalk, Parmigianino investigates the work of his role model, Raphael. His Madonna, gazing down from her throne in the clouds, is gently holding the standing child. It can be traced back to Raphael's 'Madonna di Foligno' (ca. 1511/12), who also floats in the clouds. The firm, balanced physicality of Raphael's Madonna and the calm way in which she is seated is transformed in Parmigianino's drawing into a hovering figure striving to rise upwards. The elegant lightness is heightened by the drawing technique, which establishes a relationship between the fine, transparent brushwork transitions to the light colour of the paper, thus creating an effective contrast. This sheet is probably a relatively early study for one of Parmigianino's most important works, now in the National Gallery in London: 'Madonna and Child with Saints' from 1526/27 - but it could also have been produced somewhat later, after the artist was forced to move to Bologna following the Sack of Rome in 1527.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.