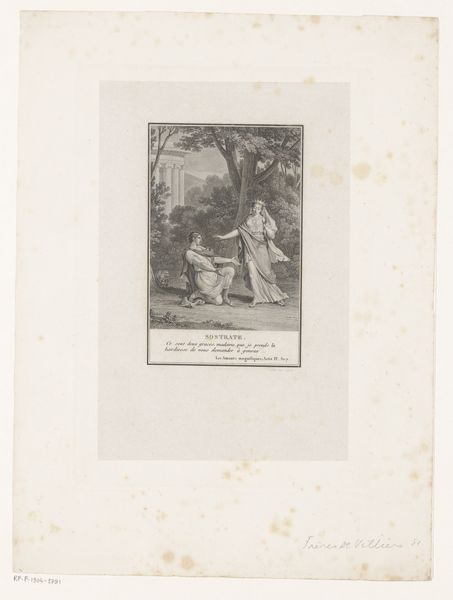

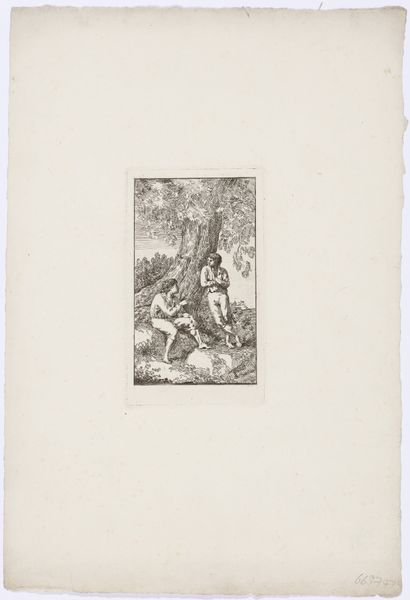

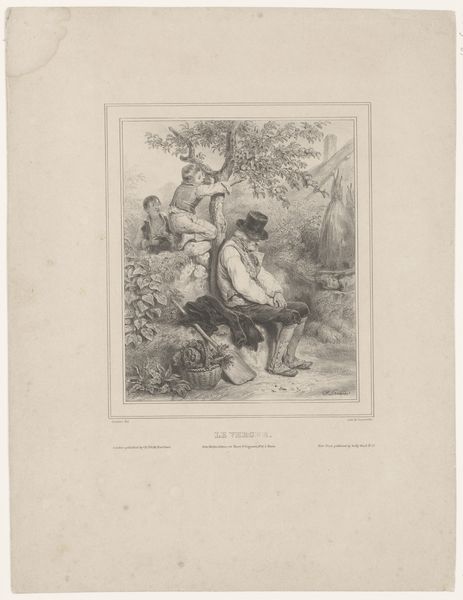

Mélicerte bezocht door haar jonge aanbidder Myrtil 1811 - 1813

0:00

0:00

emmanueljeandeghendt

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 234 mm, width 164 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Emmanuel Jean de Ghendt's engraving, "Méricerte bezocht door haar jonge aanbidder Myrtil," made between 1811 and 1813. It’s currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: My initial reaction is that it feels like a tableau vivant, almost staged. The stark contrast between light and shadow really highlights the dramatic interaction. Curator: De Ghendt, as an engraver, was fundamentally a manufacturer of images, often based on designs of others. It is interesting how this print, a multiple, reflects a desire for mass dissemination of idealized classical scenes. Look at the details in the line work, creating texture. Editor: Absolutely. The sharp lines really give the figures definition and an almost statuesque quality that aligns with the neoclassicism apparent here, despite some hints of Romanticism. It makes me wonder how the availability of such prints affected perceptions of power and representation during the 19th century. This image also echoes patriarchal themes about young male lovers at the service of a woman, as shown in mythology or, less charitably, a transaction. Curator: The labor involved in creating an engraving is considerable. It is not just the design but the execution, cutting into the metal, creating something meant to be reproducible and circulated widely to different audiences. This artwork sits at the nexus of craft, industry, and visual culture of that era. Editor: Exactly, and the circulation is key. Prints like these brought narratives from antiquity into contemporary social and political debates. Whose stories were being told and how, speaks volumes about social mores of that period. Curator: Looking closely at the materiality and mode of production contextualizes these mythological themes within an era where visual information circulated through these kinds of printed images. It raises questions of who has access to such stories, and in turn who gets to interpret them. Editor: Well, considering its historical context, I would argue this print offered a visual framework for power relationships, framing desire through idealized classicism. Food for thought about representations we still contend with. Curator: It's precisely this intersection of material making, and accessible narratives that reveals so much about art and culture in the 19th century. Editor: Agreed; through that lens, we can ask better questions about historical consumption and interpretations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.