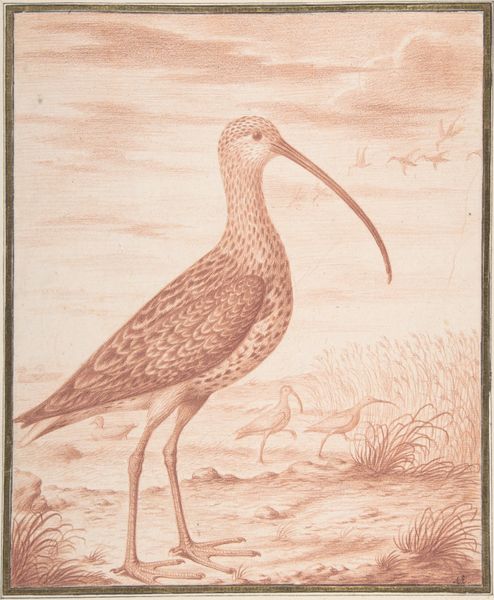

drawing, watercolor, ink, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

ink

#

pencil

#

watercolour illustration

#

pencil art

#

watercolor

#

realism

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 480 mm, height 184 mm, width 309 mm, height mm, width mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

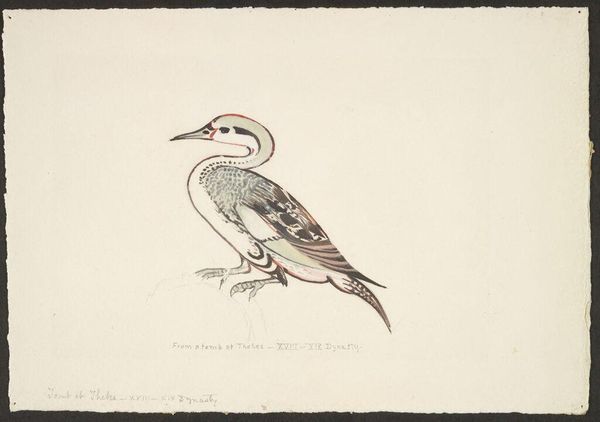

Curator: Take a look at this, it's Robert Jacob Gordon's rendering of a "Ceryle rudis," or female pied kingfisher, likely sketched between 1777 and 1786 using a mix of ink, watercolor, and pencil. Editor: The striking monochromatic scheme initially draws me in; then the texture comes alive. Those meticulously crafted feathers feel both abstract and true-to-life at once. There's a distinct air of calmness and precision. Curator: Absolutely, I think the detail he captures is remarkable. You can almost feel the texture of the feathers, and the slight washes of color really bring the bird to life, while also giving context to the physical environments. This blend of scientific observation and artistic skill speaks to a larger understanding of our ecosystem, too. It shows how much can be shown using limited material means, and how that, as a consequence, heightens perception. Editor: Agreed! It's intriguing to consider this not just as a piece of art but also a functional document from a time when understanding nature often meant documenting it visually, especially across different locations. We have a specific focus on the pied kingfisher, but there are a wealth of artistic possibilities brought by other components. Just imagine what kind of paper was used; the specific pencils that could have been favored at the time for that range of line. Was the paper locally sourced or produced through complex global trading? And if trading, who profits? Curator: That material interrogation reminds me that these works were, in a way, a product of the burgeoning scientific exploration happening then. There’s a parallel with the impulse to name and classify, which also reflects how Europeans engaged with, and often tried to control, the natural world that was not theirs to begin with. It’s a complicated legacy woven into something beautiful. Editor: Indeed. By thinking about the material conditions and cultural contexts surrounding such a piece, we can engage in an active way with what such an illustration may reveal or obscure in how the artist engaged in observing this specimen. Thank you, this really invites a fresh material-aware perception of our holdings.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.