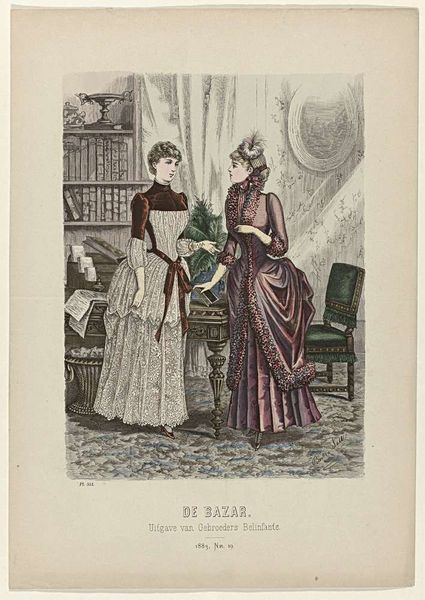

Dimensions: height 379 mm, width 268 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

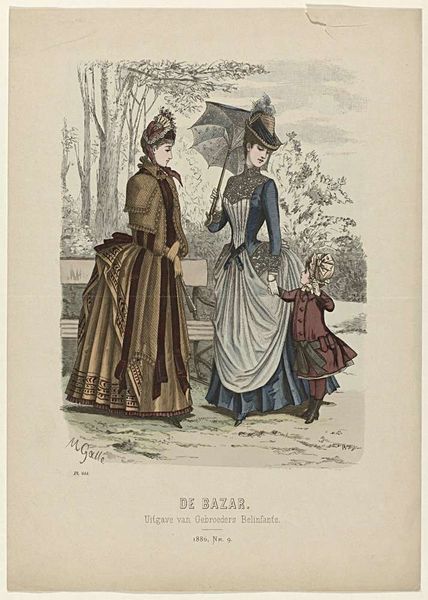

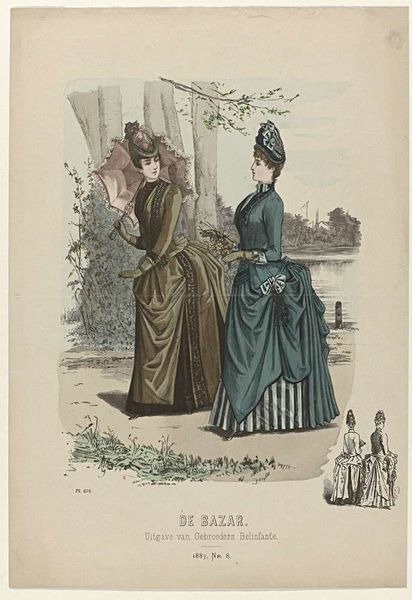

Curator: Here we have a print entitled "De Bazar, 1883, Nr. 9, Pl. 536," dating from 1883, published as part of a series by Gebroeders Belinfante. It’s a genre scene rendered, I believe, with a combination of drawing and printmaking techniques. What are your immediate impressions? Editor: Intimacy, formality... It feels almost staged, yet I'm drawn in by the contrasting textures of the fabrics. The woman on the left seems draped in shadows, a gothic romance heroine almost, while her companion shines. Like characters in a half-told story! Curator: That tension between shadow and light is very deliberate. "De Bazar," which translates to "The Bazaar," served as a fashion plate, distributed to upper-class clientele. Consider its function: it was intended to display current styles and trends. It presents the viewer not just with beautiful clothes, but an aspirational lifestyle. Editor: So, it’s early Instagram. Though, even a touch ironic for a "Bazaar," don't you think? There's this almost studied detachment in the figures’ eyes. I wonder what anxieties these clothes both conceal and reveal? Is this what fashionable depression looks like? Curator: (chuckles) Perhaps! Clothing, as social historians argue, is deeply communicative. The restrictive garments – corsets, bustles, and long skirts - enforced a particular female posture, but, perhaps more importantly, it constrained their social role. Prints such as this not only dictated style but helped in maintaining the status quo. Editor: It does seem designed to control – to almost literally define boundaries for the women it's depicting, yet at the same time I sense an element of unspoken subversion, you can feel something unresolved in that narrative glance… Almost an unspoken defiance, perhaps a hidden critique of its restrictive social context? Curator: Precisely. Though produced to reflect norms and desires, images like "De Bazar" are often fertile ground for dissecting the politics of fashion. They demonstrate how aesthetics and power entwine and can reveal what society valued and what it feared. Editor: It’s like holding a whisper up to the light and finding out what it says. It goes to show you can make statements even while seeming to make fashion. Curator: Indeed! By interrogating its aesthetics and intentions we gained profound insight, seeing how something beautiful can contain complex commentary about societal structures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.