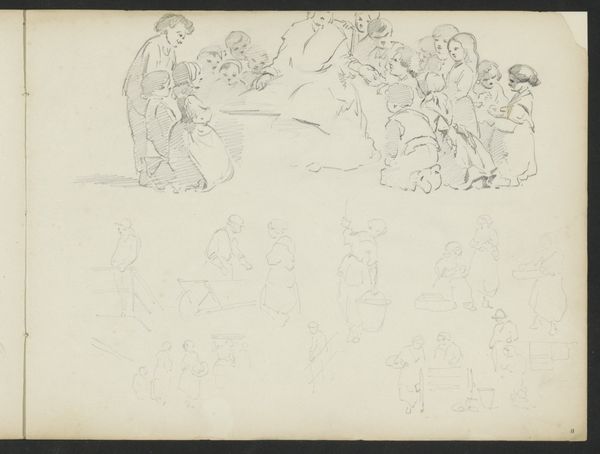

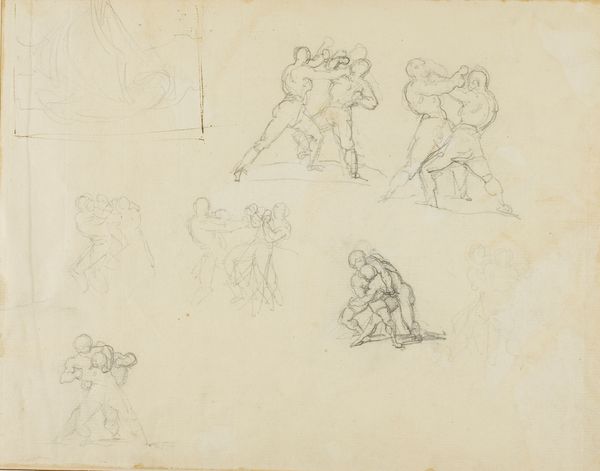

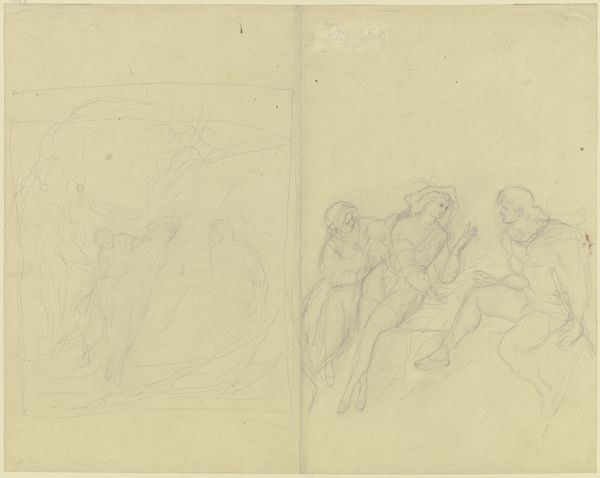

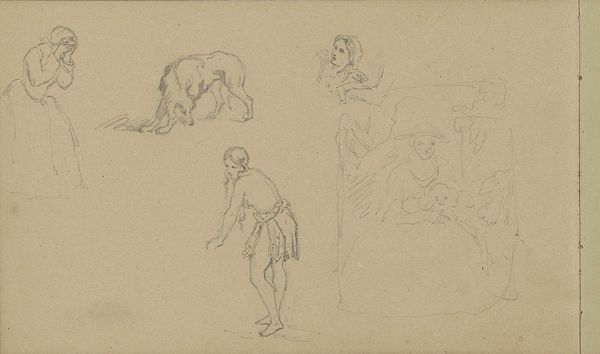

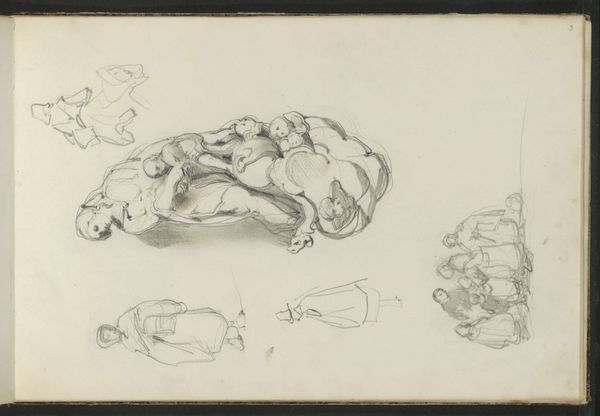

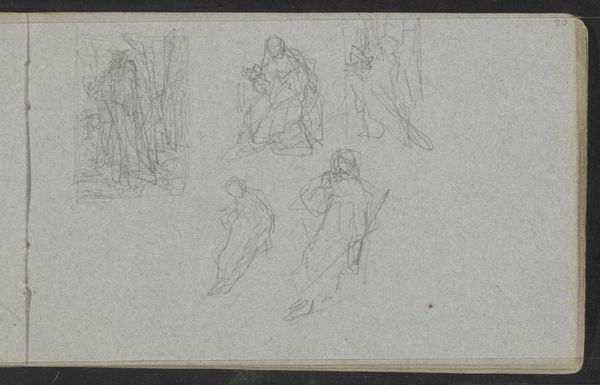

drawing, print, pencil

#

drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

pencil

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

#

male-nude

Dimensions: Sheet: 5 5/16 × 8 1/2 in. (13.5 × 21.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is "Studies after Michelangelo" by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, made sometime between 1840 and 1875. It’s a pencil drawing, and it feels very academic, almost like a practice sheet. What strikes me is how the figures seem to echo the idealized forms of the Italian Renaissance, but there’s also a raw, almost unfinished quality to them. What do you see in this piece? Curator: This work invites us to consider the power dynamics inherent in artistic appropriation and homage. Carpeaux, a 19th-century artist, is engaging with the legacy of Michelangelo, but what does it mean for a male artist to revisit and reinterpret the work of another male artist from a different historical and cultural context? How might we read this through a lens of artistic influence and power? Editor: So it's not just a drawing, but a statement? Curator: Precisely! Think about the institutional power Michelangelo held and continues to hold in art history. Carpeaux, by studying and sketching these figures, is participating in that canon, reinforcing certain ideals about the human form and artistic skill. But the unfinished nature, as you pointed out, could also be read as a subversion, a questioning of that very ideal. How do the multiple figures, some more defined than others, play into this? Editor: That's a great point. Some of the figures are barely there, ghosts of Michelangelo's originals. Almost as if to say that you can never really capture the essence of his work? Or maybe the artist wanted to represent that canonical influence by presenting a variety of possible figures? Curator: Exactly! This incomplete quality opens a space for dialogue about how artistic legacies are constructed and how artists engage with the weight of the past. What is deemed worthy of study and repetition and how is that influenced by power, gender and race? These are all relevant questions that are open to a diversity of interpretations. Editor: I never considered it that way. I was so focused on the surface. Curator: Often the most challenging, and rewarding, aspects of art lie beneath the surface. Thinking about art from the perspective of what we call "critical intersectionality" helps to unveil those intricacies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.