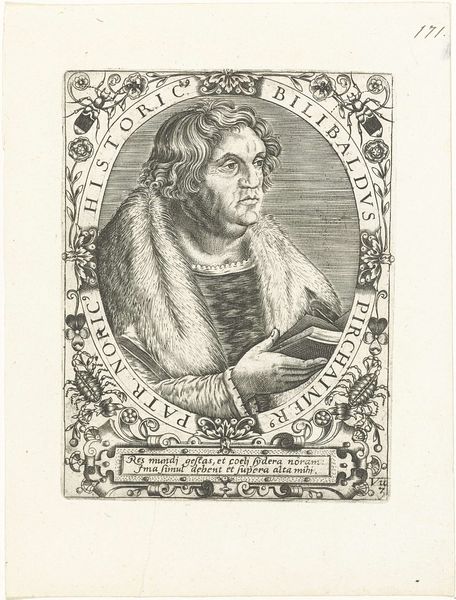

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

caricature

#

portrait reference

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 315 mm, width 220 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

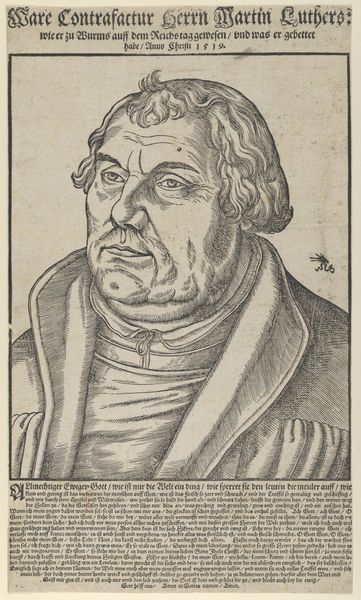

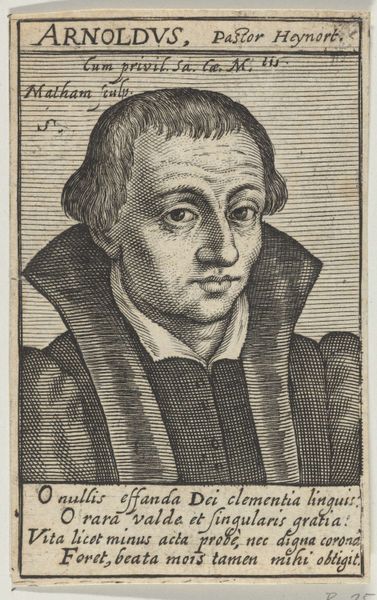

Curator: Welcome. We're standing before "Portret van Martin Luther," an engraving created sometime between 1565 and 1611 by Paulus van Wtewael. My initial reaction is the starkness of the light, a chiaroscuro effect typical of the Northern Renaissance. The starkness almost accentuates Luther’s prominent features. Editor: It's striking, yes, in its visual impact. I’m immediately thinking about the printing process here. The density of line work suggests an artisan who painstakingly rendered each mark. Was it printed from a copper plate perhaps? One thinks about the labour behind producing multiples, disseminating the image of Luther widely. Curator: Indeed, it's the deliberate composition which commands attention. The artist utilizes the graphic nature of the engraving to define texture. Notice the contrast of the curls in his hair compared to the austere lines of his robe. Semiotics point us to reading that opposition: the earthy man versus the man of God. Editor: Good observation. However, it leads me to considering the socioeconomic context. Engravings like this had power beyond aesthetics, disseminating ideas rapidly, cheaply. And it raises interesting questions of patronage. Who commissioned this? For what purpose was this mass-produced portrait of the reformer made available? Curator: Agreed, the question of patronage adds a rich layer of understanding. Consider the inscriptions too, around the image. There's the birth and death information presented inside a heart-shape and below, two stanzas. Editor: The texts emphasize the creation of community via consumption: "Dat machonen blefen in mijn leuen,"—or "That must blossom in my life." Consider how powerful it would be, for someone of the reformation to encounter this image! The act of possessing this small material image connects them not just with Luther, but the act of creating change. Curator: It highlights the subject's gravitas. The face is almost like a landscape etched into the material itself. He has presence that echoes across time. It’s more than just a record; it's a construction. Editor: Absolutely. These prints played an integral role in shaping the cultural landscape of their time, far beyond mere representations of historical figures. They are remnants of socio-religious identity. Curator: Looking at this engraving allows us a potent insight, providing both visual complexity, and insight into cultural dissemination and individual identity. Editor: And underscores the capacity of art to not only reflect an age but shape the lives of the individuals embedded within it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.