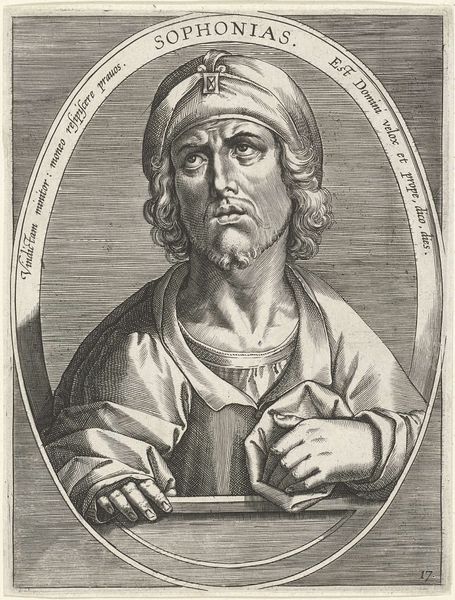

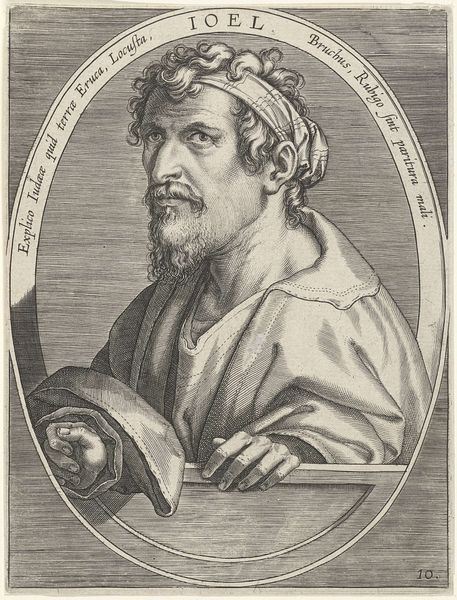

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 130 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Standing before us is “Obadja,” an engraving crafted in 1613 by Cornelis Galle I. You'll find it here at the Rijksmuseum. My initial impression is, well, restrained. There's a quietness to his gaze, a contemplative mood that sort of belies the drama usually found in Baroque portraits. Editor: Restrained, perhaps, but it also feels like a very loaded silence, doesn't it? Obadiah, even in visual representations, is situated between divine judgement and societal reckoning. This is not just a portrait; it’s a historical document reflecting on power dynamics and prophecy. Curator: Ah, you've hit on something. His steady gaze almost penetrates you. I’m struck by how he sits, with those incredibly detailed hands, one atop the other, like he carries the weight of untold secrets, ready to share, or maybe warn, with all that's to come. There is even some latin text running above and behind him in an oval, adding more context to his portrait, saying, "Vos ego Idumæos et Gentes arguo: vobis / Nuntio luctificum prouidus interitum." Editor: The text that encircles him reinforces that tension, framing Obadiah as a figure of warning, an active participant in a discourse of justice. "I accuse the Idumeans and the Gentiles." So, we understand him not only as an individual but as an indictment against historical oppressions. Galle, perhaps, encourages us to see these ancient narratives reflected in the power structures of his own time. Curator: And then there’s the craftsmanship! The texture on his turban, the detailed fabric of his robe – everything meticulously rendered to capture light and shadow. Do you see how it brings a sense of almost unsettling hyperrealism, as if we could reach out and touch the rough fabric? Editor: It’s a fascinating contrast – that realism set against this larger symbolic landscape. The print becomes a meditation on seeing and being seen, on witnessing the past so we may recognize the echoes in our present, while also revealing biases related to gender and other intersectional domains. Curator: Right. Looking at it this way, it's a deceptively simple artwork, offering complex ideas about personal and cultural narratives through line and light. Editor: Absolutely. It becomes a mirror reflecting not just a biblical figure, but ourselves and our place in the unfolding drama of history and ethics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.