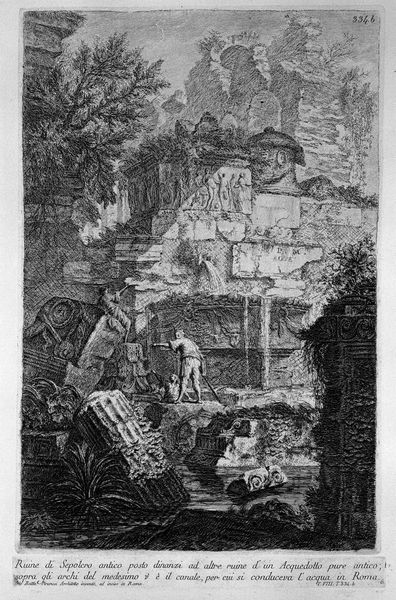

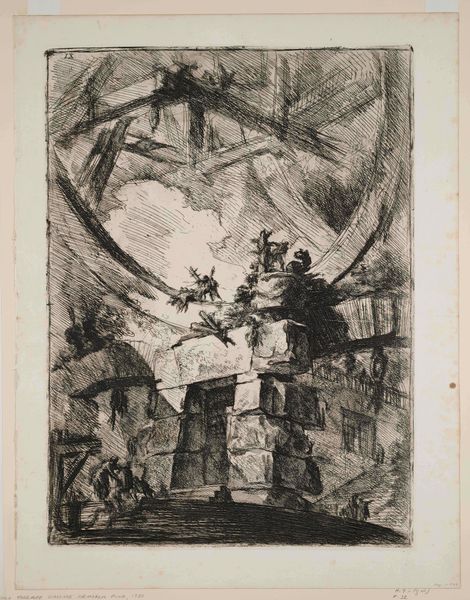

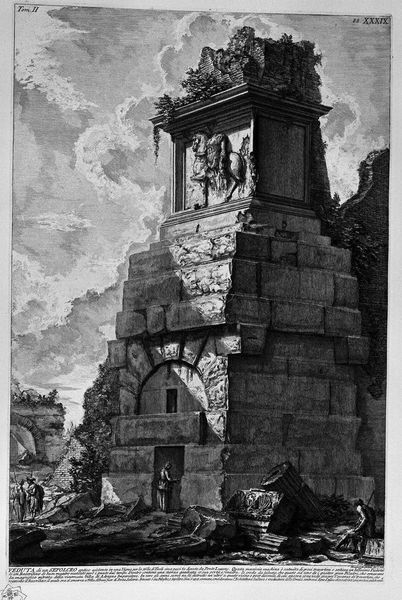

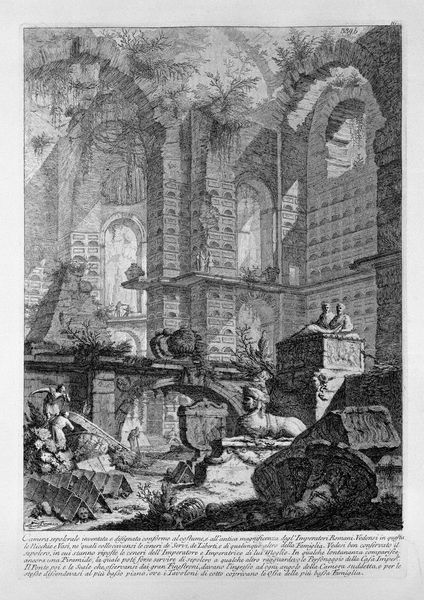

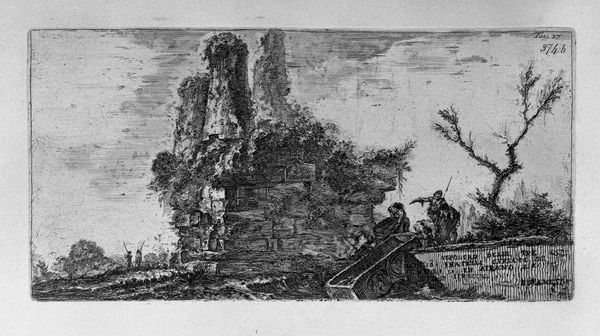

The Roman antiquities, t. 3, Plate XIV. View of a tomb outside Porta del Popolo on the ancient Via Cassia called by the vulgar: the tomb of Nero.

0:00

0:00

print, etching, engraving, architecture

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

#

architecture

Copyright: Public domain

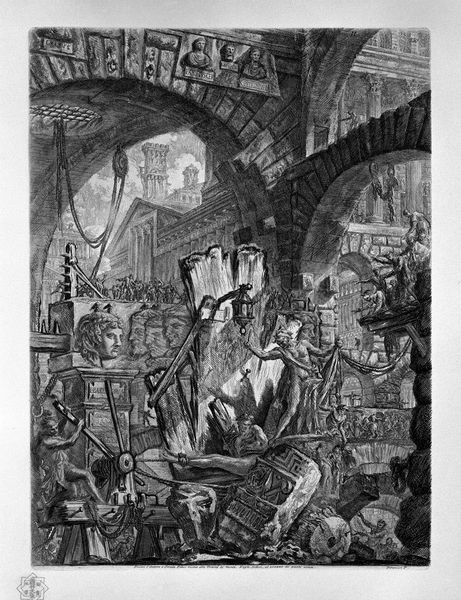

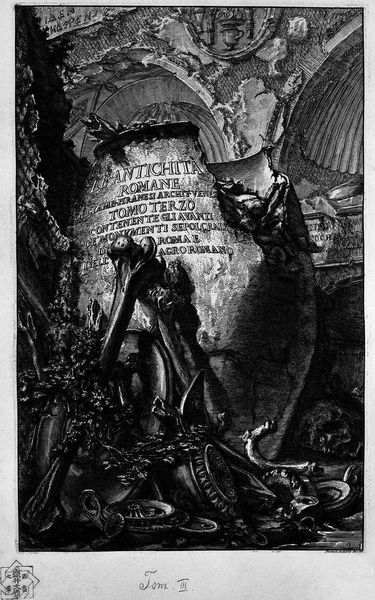

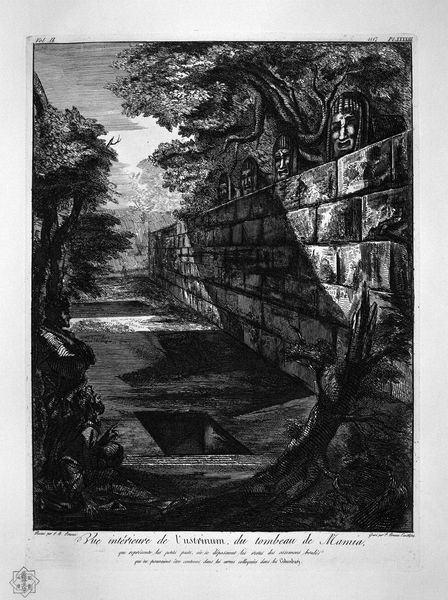

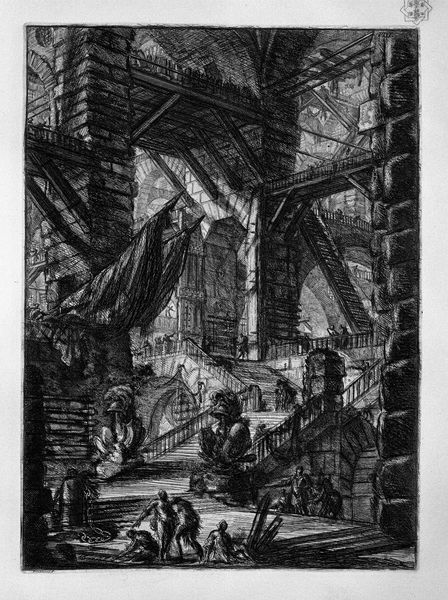

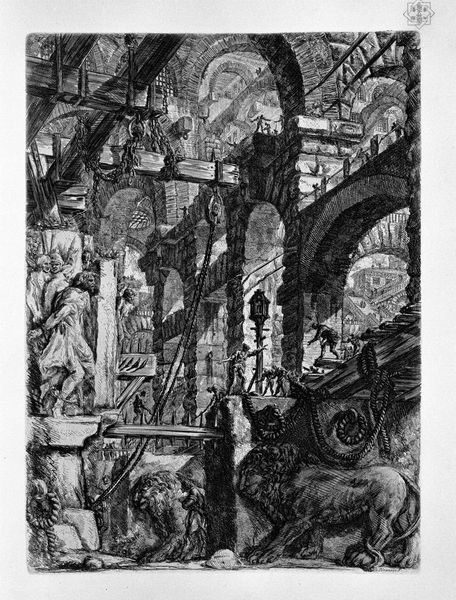

Curator: This is a fascinating piece from Giovanni Battista Piranesi, titled "The Roman Antiquities, t. 3, Plate XIV. View of a tomb outside Porta del Popolo on the ancient Via Cassia called by the vulgar: the tomb of Nero." It's a print, using etching and engraving techniques, showcasing a tomb from antiquity. Editor: It’s so dramatic! The light and shadow create such a sense of foreboding. It feels both majestic and deeply melancholic. Curator: Piranesi was known for these dramatic perspectives and romanticized views of Roman ruins. This work really embodies the Neoclassical fascination with the past, but with a distinct Piranesian flair. Look how the figures are dwarfed by the architecture. What’s that suggesting, historically? Editor: Right, it plays with scale, doesn't it? It diminishes the contemporary figures to highlight the monumentality – and perhaps the faded glory – of the Roman Empire. The “tomb of Nero,” regardless of whether it *actually* is his, operates as a powerful symbol of power, death, and the cyclical nature of history. I'm struck by the idea that this supposed symbol of Nero could be seen in a popular way "by the vulgar," as the artist himself indicated. What statement about class differences or public opinion does the artist try to make by capturing that specific viewpoint? Curator: Indeed! We see these recurring themes reflected across Piranesi’s work as he investigates the social and cultural history through prints such as this. Editor: Absolutely. The decay is so palpable, it’s hard not to see it as a commentary on the impermanence of even the grandest empires. I'm really fascinated with the political implications: How the visual representation of the fall of power operates as a constant reminder of the ever-changing sociopolitical context. Who benefits, who doesn't and how do these kinds of work function as either propaganda or warning in modern societies? Curator: Piranesi's work also challenges our notions of accuracy and representation. He was known to exaggerate details, play with perspective, so that these works themselves function almost like theoretical statements about civic architecture and the role of power, especially in 18th century Rome. Editor: Yes, precisely! He’s not just documenting, he’s constructing a narrative, which, in the end, raises some exciting ideas for future historical exploration. Curator: Thinking about this today helps reveal those layered historical contexts. Editor: It does. It pushes me to question who benefits and who is oppressed through art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.