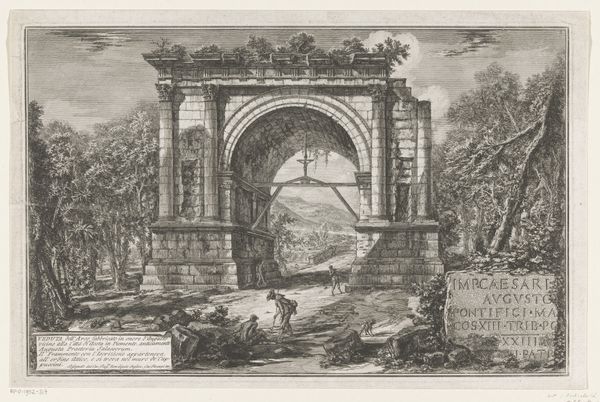

View of the Arch built in honour of Augustus close to the city of Aosta ... 1773 - 1776

0:00

0:00

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

romanesque

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: 258 mm (height) x 395 mm (width) (plademaal)

Curator: This is an engraving by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, dating from 1773 to 1776. The piece is entitled, "View of the Arch built in honour of Augustus close to the city of Aosta..." It’s part of the collection at the SMK, the Statens Museum for Kunst. Editor: What a compelling scene! The heavy, almost crude, stone of the arch set against the soft landscape has such a brooding presence, even in a small print. It feels monumental, but somehow fragile, too. Curator: I find Piranesi so interesting from a materialist perspective. Consider his choice of engraving, a printing technique allowing for mass production. His “Views of Rome” and other prints like this one weren’t necessarily considered "high art" at the time. These prints made depictions of Roman antiquity available to a wider public, functioning almost as postcards or souvenirs. Editor: Exactly. Piranesi isn’t simply presenting us with an image; he's engaging in a dialogue about power, colonialism, and the gaze. Think about who had access to these images and what it meant to possess them in the 18th century, solidifying a certain understanding and often a romanticized and self-serving narrative about antiquity. The labourers in the foreground make this explicit: their lives a stark contrast to the enduring glory of the arch. Curator: And what is so remarkable, too, is Piranesi’s hand. I’m intrigued by his labor and how he renders crumbling details with precise lines, hinting at the work of past artisans who labored to build the original arch. Also, the physicality of engraving, the marks the tools leave on the plate - those all point to human endeavor. Editor: Right. Consider too that, these detailed depictions might’ve influenced the restoration and preservation movements, intertwining art, politics, and cultural memory. Each mark serves not just as a visual element but also as a testament to how we selectively remember and value different parts of our history, all within complex sociopolitical frameworks. Curator: It really is a study in contrasts - permanence and transience, decay and memory, the individual artisan and mass production. Editor: It leaves you questioning not only what you’re seeing, but also the implications of who gets to see it and what meanings they assign to it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.