Rest on the Flight into Egypt and the Miraculous Field of Wheat c. 1518 - 1524

0:00

0:00

oil-paint

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

earthy tone

#

underpainting

#

painting painterly

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: 13 1/2 x 19 1/4 x 1/4 in. (34.29 x 48.9 x 0.64 cm) (panel)

Copyright: Public Domain

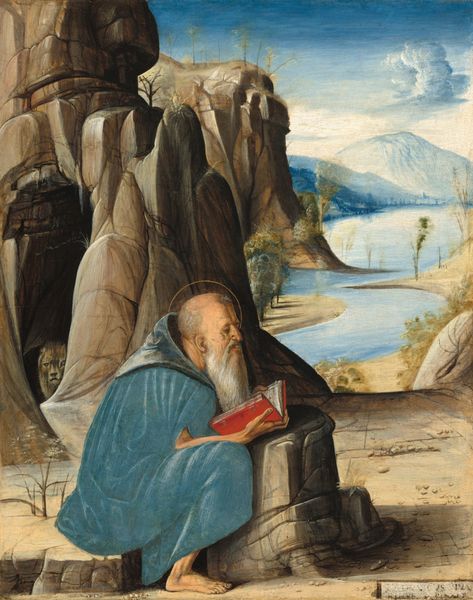

Editor: So, here we have Joachim Patinir's "Rest on the Flight into Egypt and the Miraculous Field of Wheat," made sometime between 1518 and 1524 using oil paint. I’m immediately struck by how this biblical scene is almost swallowed by the landscape. It makes me wonder – what’s going on here? What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a potent commentary on labor and its relationship to both the divine and the earthly. Notice how Patinir gives almost equal visual weight to the field laborers and the resting Holy Family. He is very deliberately merging sacred narrative and ordinary toil. Editor: I see that, but why give such prominence to manual labor? Curator: The prominence elevates the materiality of their world: the texture of the earth, the sweat of labor, and the tangible result of their efforts - wheat, the grain that feeds society and symbolically represents Christ. The wheatfield miracle serves not just as divine intervention, but also as an affirmation of the value inherent to that labor. Editor: So, the painting challenges a typical hierarchy, maybe blurring distinctions between the sacred and the profane? Curator: Exactly! Patinir reframes our understanding. Consider the implications of using oil paint. The cost, preparation, and layering of colors represented significant material and labour investment to render not the divine directly, but a landscape dominated by human labor. How does that resonate with you? Editor: It makes me realize I was focusing too much on the religious narrative and not enough on the social implications. It’s like he's saying salvation isn't just about faith, but also about our relationship to the physical world and the work we do. Curator: Precisely. He is celebrating the material basis of life, intertwining divine miracle with human necessity. It encourages viewers to see holiness not apart from the working world, but infused within it. Editor: That’s given me a whole new way to think about Northern Renaissance painting! I thought about it as purely religious iconography, and I’ve totally missed the cultural relevance of labor. Curator: These landscapes allow us to see labor as part of a social and spiritual fabric. Always consider the material processes behind the art.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

This painting depicts scenes from the Bible related to the so-called Massacre of the Innocents. King Herod, upon hearing that a “King of the Jews”—Jesus Christ—had been born in Bethlehem, orders the slaughter of all male children in and around the town in order to protect his claim to the throne. Jesus, Mary, and Joseph—the Holy Family—escaped to Egypt. While the infanticide rages in the distance, Joseph, on the left, collects water from a spring that appeared as a miracle of God. To track down the Holy Family, Herod’s soldiers interrogate farmers in their fields. The farmers truthfully answer that the family passed when the wheat seed was being sown into the ground. Through divine intervention, the wheat grows to its full height overnight, suggesting that the family had passed several months earlier and saving them from certain death.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.