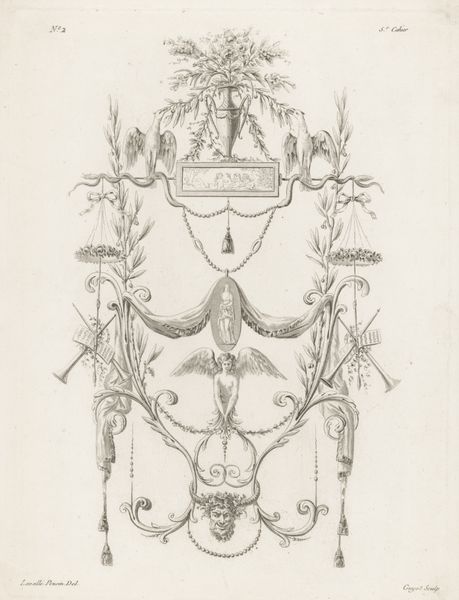

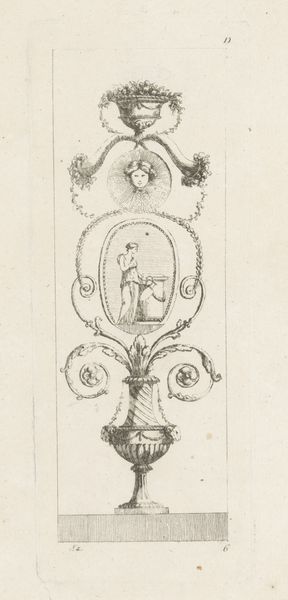

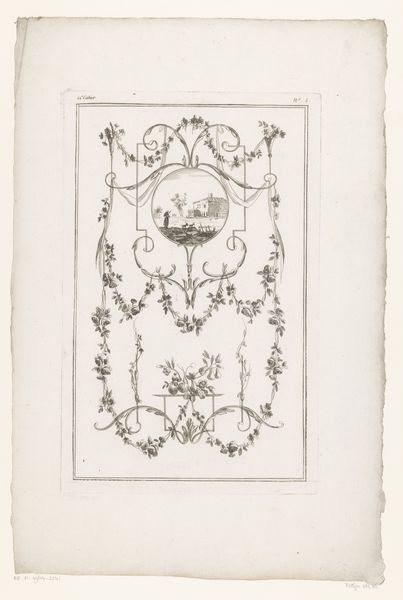

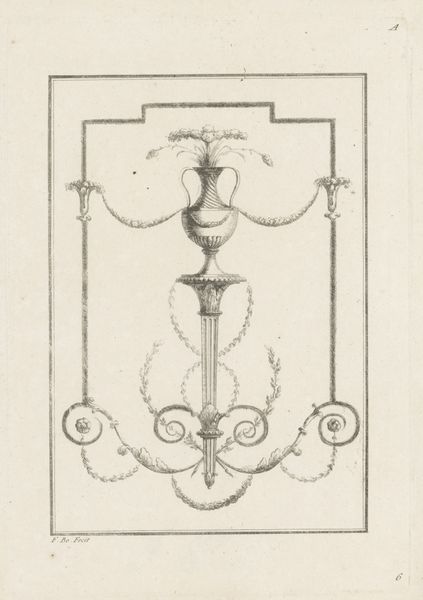

Dimensions: height 212 mm, width 147 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is “Vaas met arabesken,” or “Vase with Arabesques,” an engraving by Juste Nathan Boucher, dating from 1752 to 1782. The detail is incredible. It feels very ornate, almost like a blueprint for high society tableware. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Boucher’s engraving offers a glimpse into the visual language of 18th-century power. The vase, framed by classical motifs like the female head and symmetrical flourishes, speaks to a culture deeply invested in hierarchy and the display of status. Consider how the 'arabesque' itself—originally an Islamic art form—is repurposed here within a European context. Who is benefiting from this appropriation? Editor: That’s a perspective I hadn't considered. So the vase isn't just a decorative object? Curator: Not at all. It's a statement. The precise lines and balanced composition reflect a desire for order and control, values prized by the aristocracy. Moreover, the very act of engraving—of creating multiple copies—democratizes this symbol of status to some degree, even while reaffirming its elite origins. How might such readily available imagery influence public perception? Editor: I guess it makes something that’s meant to be exclusive more… aspirational? It's like advertising luxury to a wider audience. Curator: Exactly. And by understanding that dynamic, we can begin to unpack the complex social and political meanings embedded within even seemingly simple decorative arts. It becomes less about the beauty of the object and more about the power structures it represents and reinforces. Editor: I see that now. Looking at it again, the vase feels less like a pretty design and more like a symbol loaded with historical context. Curator: Indeed. And that, ultimately, is the power of art history – revealing those hidden stories and prompting us to question the world around us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.