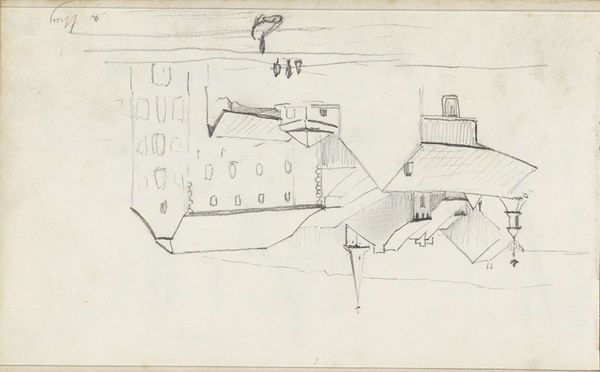

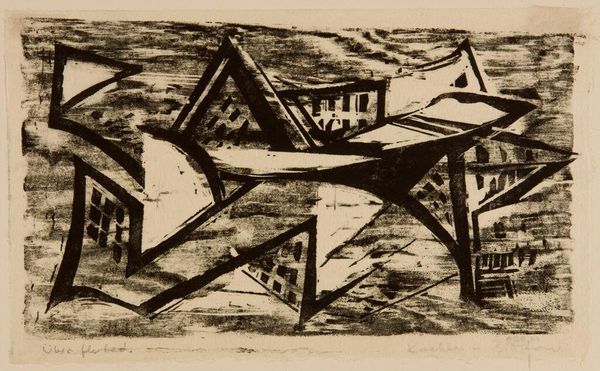

Uritzky Square. General view. Design sketch for the celebration of the First Anniversary of Revolution in Petrograd. 1918

0:00

0:00

mixed-media, painting, paper, mural

#

cubism

#

mixed-media

#

painting

#

constructivism

#

paper

#

mural art

#

geometric

#

abstraction

#

russian-avant-garde

#

cityscape

#

mural

#

modernism

Copyright: Public domain US

Curator: Here we have Nathan Altman's 1918 mixed-media work, a design sketch called "Uritzky Square. General view. Design sketch for the celebration of the First Anniversary of Revolution in Petrograd." It offers a fascinating glimpse into post-revolutionary artistic expression. Editor: My first thought is… stark. The geometry is so aggressive, so intentionally disrupting traditional perspective. It's as if the revolution is visualized, shattering old forms and demanding a new way of seeing. Curator: Precisely. Altman, deeply embedded in the Russian avant-garde, uses Cubo-Futurist and Constructivist principles to translate revolutionary zeal into visual language. These weren’t just aesthetic choices; they were political statements. Altman was deeply involved in theater design before returning to Petrograd to use his design skills in public celebrations after the Revolution. Editor: Red and green are dominant, yet in this context, it’s less about nature and more about power. Red for the revolution, obviously. And the green blocks at the bottom with text on them are also intriguing; can we see them as a direct communication of propaganda? Curator: Absolutely. These geometric blocks are a common Constructivist design feature, and, in line with public declarations of support to the revolution from the common people, Altman inscribes, “Proletarians of all countries, unite!” The celebration of the revolution in public space was carefully crafted. Editor: The layering of shapes and colours gives an impression of dynamic movement. Look at the pillar rising like a spire from what should be a public place – a place where the statue of Alexander might be. It becomes an echo chamber, not a monument, representing more of a feeling or mood that evokes power in a newly reconfigured urban centre. Curator: It's a powerful intersection of art and politics. Altman designed other murals, decorated trams and agit-vehicles to support revolutionary fervor; we should not forget the material hardships and daily conditions on the streets that influenced Altman's work in making political dreams a lived reality. These abstract forms served a clear, utilitarian, socio-political aim. Editor: Thinking about Altman's choices, there's this feeling of simultaneously building something new, yet doing away with past meanings. The picture plane looks brittle; are we able to reassemble them, or is our attempt pointless when the painting has said all there is to be said about this place, Uritzky Square? Curator: Indeed. It provides critical insight into understanding how artworks, regardless of aesthetic predilections, become deeply embroiled in complex social fabrics, especially in the wake of immense societal upheaval. Editor: The raw emotion of this piece lingers. It's not just about how it looks; it's about what it meant and, arguably, continues to mean as a testament of societal change viewed through the lens of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.