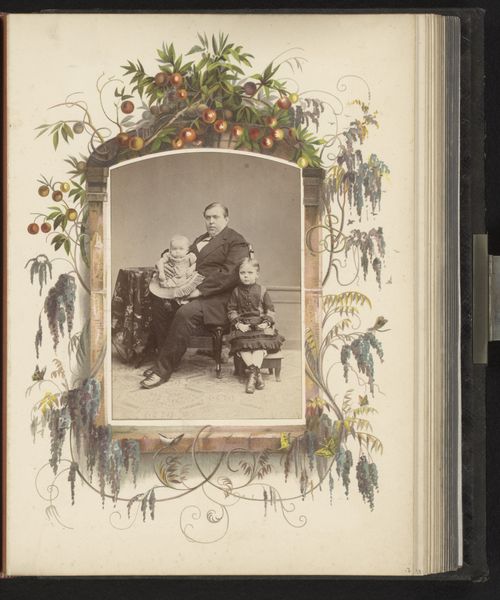

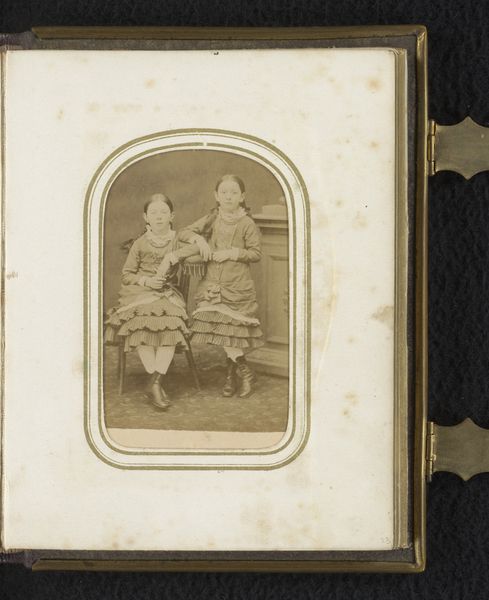

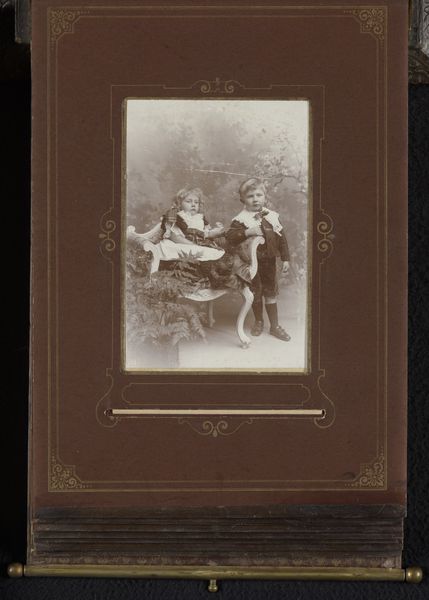

photography

#

portrait

#

photography

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Adam Clark Vroman’s photograph, "Zuni Water Carriers," taken around 1900. Editor: It's striking how stoic they appear. Their postures, bearing the weight, communicate an incredible strength but also perhaps a resignation to the arduous task before them. Curator: Precisely. The photograph, printed as a contact print, freezes a moment laden with historical context. These women aren't simply carrying water; they are enacting a vital ritual and societal role deeply embedded in their Zuni culture and cosmology. The vessels themselves atop their heads—do you notice how similar in form they are? Round, receptive, maternal—evoke cycles of life, renewal, sustenance. Editor: Right, and the cultural significance of water, especially in arid regions, can't be overstated. But looking at it now, there’s also an unavoidable colonial gaze at play. Vroman, like many photographers of that era, documented Indigenous people, often framing them within a narrative of “vanishing races.” How much does this representation reinforce those power dynamics, even if unintentionally? Curator: The 'vanishing race' narrative is certainly there, but Vroman's approach differs somewhat. He lived among the Zuni for extended periods. Still, we cannot dismiss the inherent power imbalance in the act of representation. Look closer: The women's attire, the clay jugs, even the adobe walls serve as visual cues that feed into prevailing ideas about the "primitive." They echo symbolic meanings associated with Indigenous cultures through the white lens. Editor: I wonder, looking at their expressions... I'm seeking signs of resistance, perhaps. Knowing the history of forced assimilation, land seizure, what kind of burdens did they really carry. It’s tough, analyzing historical portraiture – especially when grappling with photography's own problematic colonial past. I'm compelled to look for what isn’t explicitly revealed. Curator: Absolutely. What is deliberately shielded or indirectly symbolized often outweighs the immediate details. Even the very act of photographing is symbolic. Consider how each subject uses gestures and objects within the scene to speak about her cultural and personal values: How will future generations carry on cultural memory despite ongoing disruptions from contact and colonization? Editor: It’s so critical for museums and galleries to frame artworks such as this with these historical and social tensions at the fore. That the representation doesn't perpetuate stereotypes or contribute to a romanticized view of the past but pushes towards truth. Curator: It reminds us that the visible realm only tells half the narrative. Visual representation intersects culture, leaving a residue in individual and collective experiences. The challenge lies in constantly decoding, unraveling, and respecting layers of complex heritage in every artwork we view. Editor: Very much so. This single photograph sparks so much needed debate.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.