photography

#

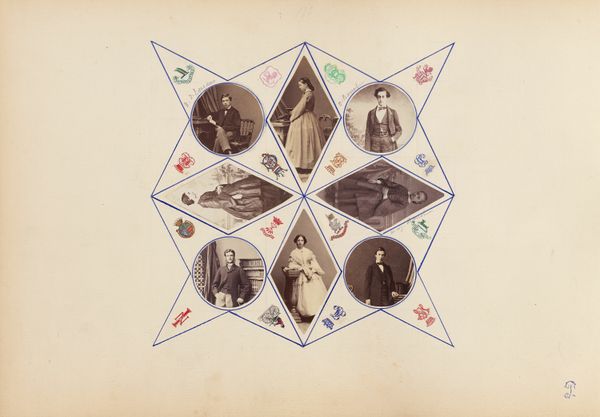

portrait

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

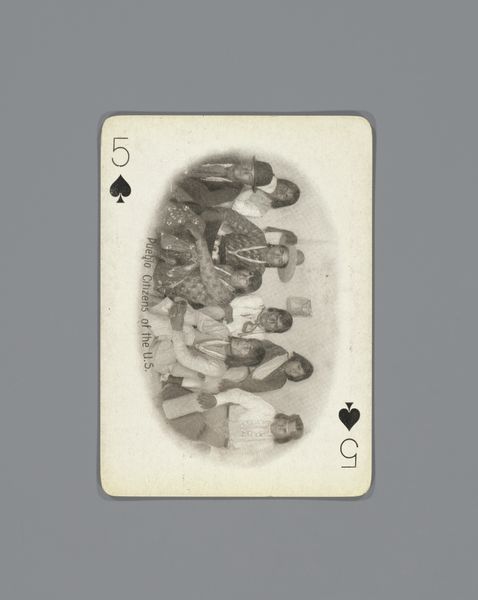

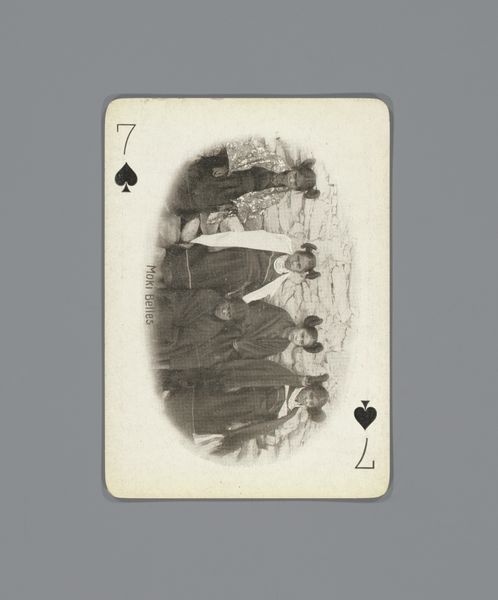

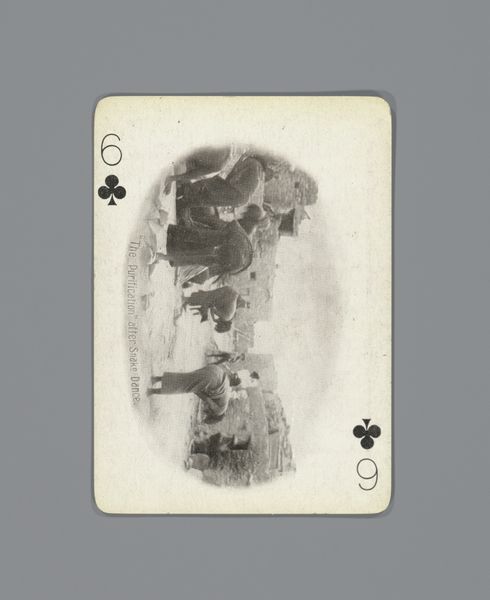

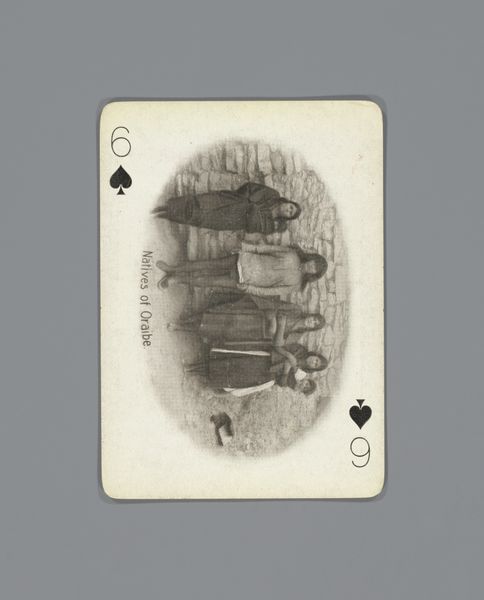

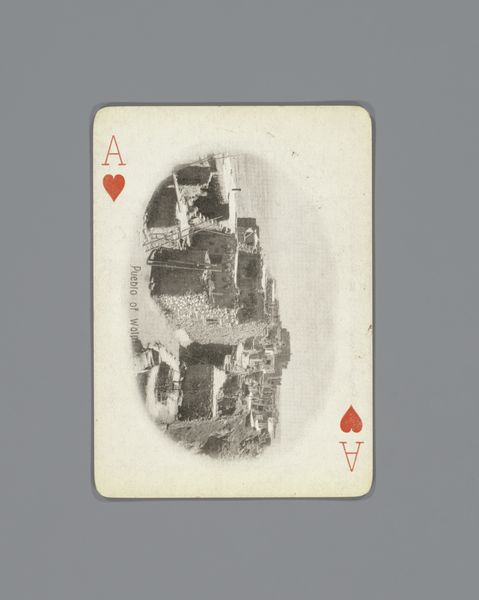

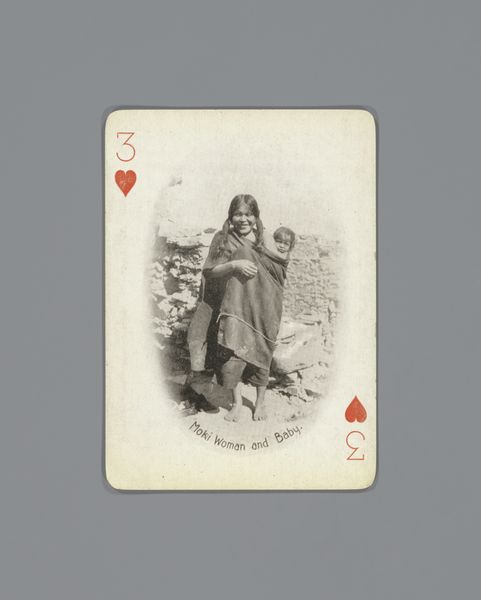

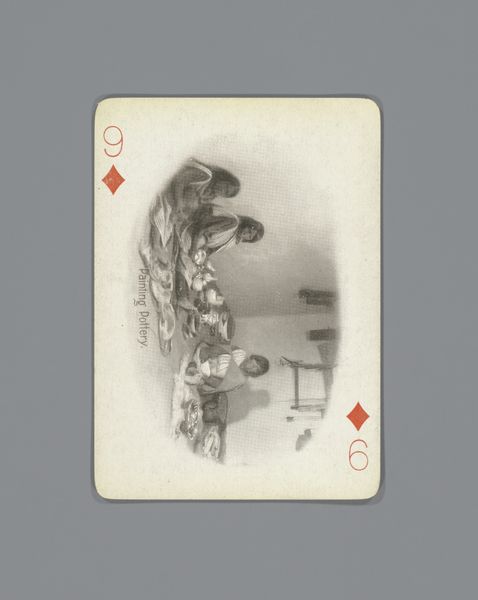

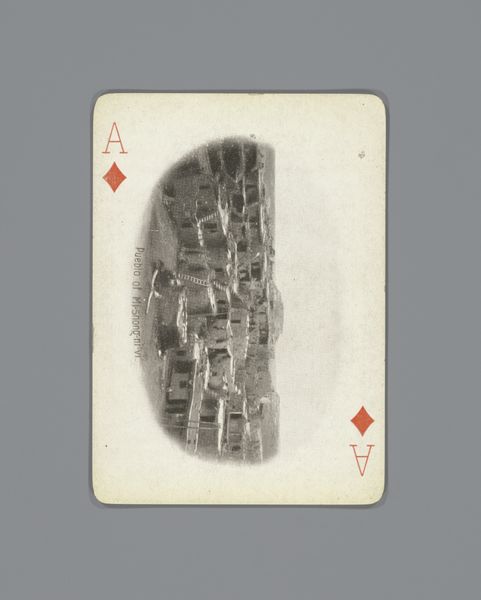

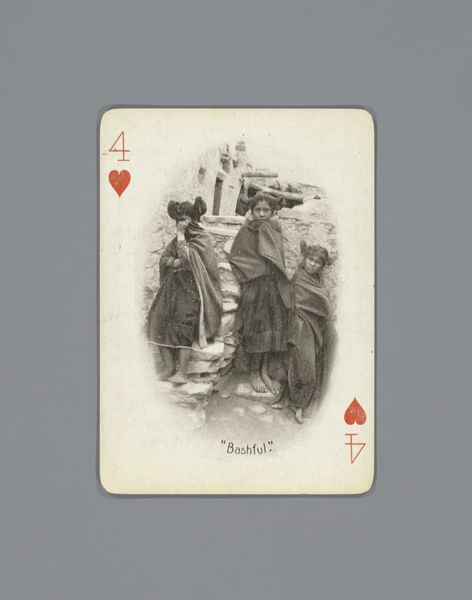

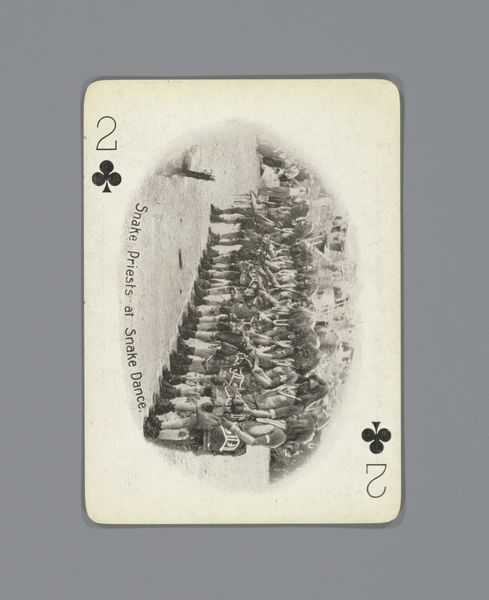

Curator: Here we have Adam Clark Vroman’s "A Family Group," a photograph from around 1900. The composition, the way the figures cluster together, feels so intimate. Editor: It strikes me as unexpectedly haunting, you know? Like peering into a lost world, even though it's supposed to be this commonplace image of family. There's a melancholy stillness that almost makes my throat tighten. Curator: And there’s a reason for that feeling. Vroman sought to capture the reality of indigenous life at a time when governmental policies were actively seeking its eradication, with a focus on photography among the indigenous communities of the American Southwest. Editor: Ah, the shadow of forced assimilation. That informs everything, doesn't it? You look at those faces, the directness of their gazes and there's defiance, sorrow. You think you see joy in their expression, but with what backdrop? It really puts the picture's sentiment in context. Curator: Absolutely. Understanding the social and political dynamics of the time allows us to see beyond the surface of the portrait and appreciate the complexities of identity and survival within those intersectional contexts. It becomes an act of resistance. Editor: Makes you wonder about the photographer’s intentions, his ethical stance as an artist of sorts, coming from outside. Was he complicit, just documenting what was there? Curator: The intentions and actions of individuals, especially in that position, should always be interrogated. What are the underlying narratives behind the visual and behind whose viewpoint are these stories being shared? How do these depictions perpetuate certain viewpoints, or challenge stereotypes? Editor: It leaves me with that deep discomfort—which, in a way, feels like what art *should* do. Should rattle us out of our easy assumptions, push us to acknowledge complexities and uncomfortable truths, make you ponder and question all you once were certain about. It is a bittersweet sentiment, I think, but still sentiment. Curator: Yes, there is the inherent tension and the act of visual representation can contribute toward something more profound when the historical dynamics, the inherent structures of inequality and power, are given precedence in conversations of context and interpretation. It becomes a dialogue then.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.