Copyright: Public Domain

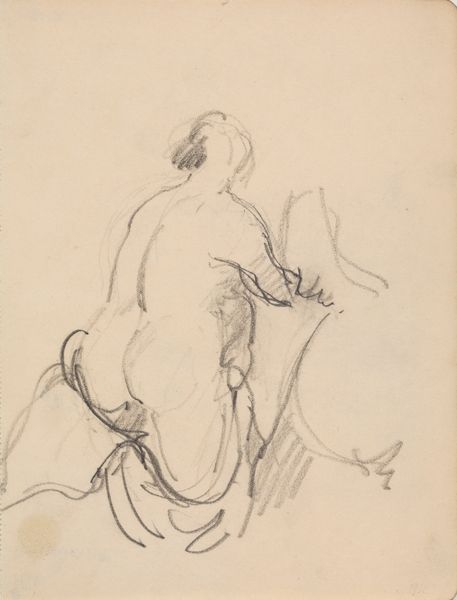

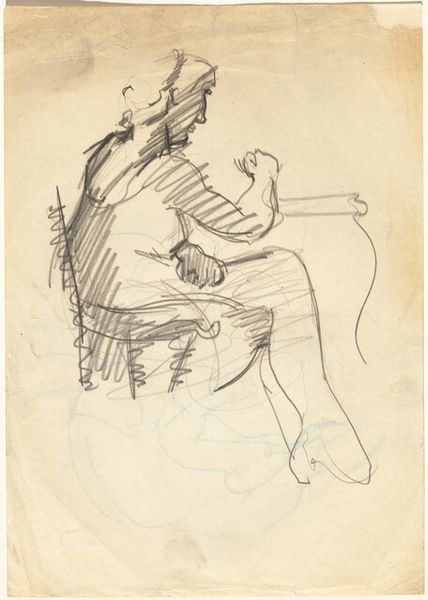

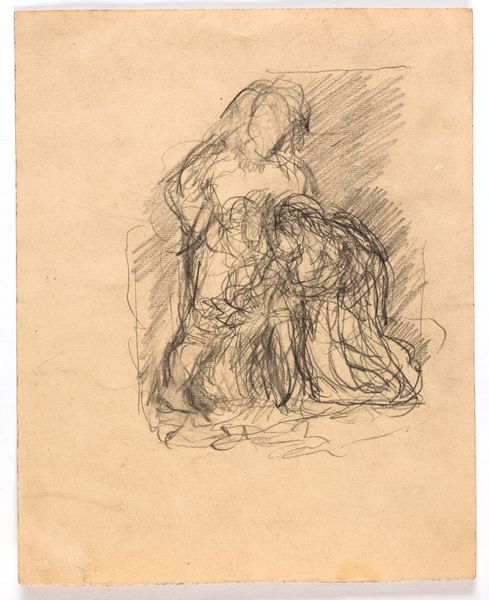

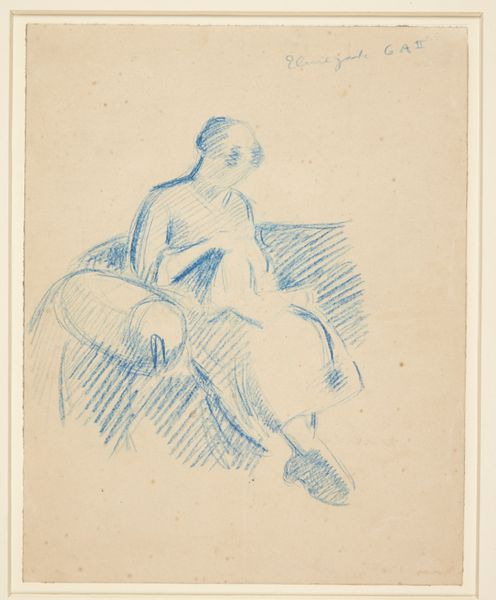

Curator: Look at this drawing by Otto Scholderer, made in 1880. It's titled "Little boy with standing dog," and is currently held here at the Städel Museum. It looks like it's executed primarily in pencil and charcoal. Editor: It’s charming! Makes me think of sketches found in old storybooks. It has such a soft, almost fleeting quality. Like a memory barely held onto. Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the paper itself. Consider its production and the materiality of drawing in the late 19th century. Chalk and charcoal would have been relatively inexpensive and readily available, making this kind of work accessible to a wider range of artists. What's the purpose for its making, I wonder? Editor: True, but look at the way Scholderer uses those readily available materials. The rapid, almost scribbled lines give the impression of movement, as if the dog might trot off at any moment. And there's something poignant about the contrast between the child’s presumed innocence and the rather watchful gaze the dog seems to be giving. Curator: Absolutely. I mean, we could think about what the rise of industrialization might have done to relationships between human beings and the animal world; such bonds could be viewed, cynically perhaps, as forms of reassurance against an alienating modernity. How labor affected families too, with fathers and children more and more absent as new economic patterns shifted during that time. Editor: That is one way of seeing things! But, if you allow for some imagination, the roughness of the medium amplifies this work’s intimate mood for me, actually heightening that sense of genuine affection. It feels quite romantic, actually. Is this simply a moment observed or something deeply felt that's committed to paper? It’s difficult to ignore such an appeal, I think. Curator: Perhaps so. Still, the act of rendering such scenes contributes, perhaps unconsciously, to the romanticization of certain classes of individuals during that epoch, given the dynamics of supply and demand in the cultural sphere, wouldn’t you say? What is included in an image is as important as what is excluded. Editor: True, there’s always that. But for now, let me relish the feeling of a private world glimpsed, a whisper across time. It’s a compelling drawing; simple, perhaps, but effective and genuinely heartfelt in its expression. Curator: Agreed. On a second viewing, its stark presentation and the boy's relative blank stare actually render an understated vulnerability I hadn't noticed at first. Fascinating.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.