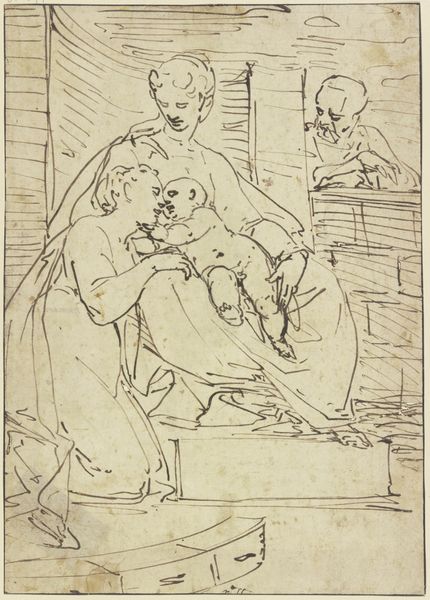

One of the Three Kings Adoring the Virgin and Child c. 1635 - 1640

0:00

0:00

rembrandtvanrijn

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

line

#

pen

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 177 mm, width 159 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Rembrandt van Rijn’s drawing, "One of the Three Kings Adoring the Virgin and Child," dating from about 1635 to 1640. It’s rendered in pen and brown ink on paper. The lines are so fluid and quick. What's most interesting to you about this work, particularly in relation to the era it was created? Curator: What strikes me is how Rembrandt uses a traditional religious scene, the Adoration, but infuses it with a distinct social commentary through his artistic choices. How do you see this operating within the context of the Baroque period? Editor: Well, Baroque art often emphasizes grandeur and drama. However, Rembrandt’s drawing, even in its sketch-like quality, seems more intimate, more… human. The Virgin doesn't appear idealized, and the King seems… humble. Curator: Exactly! It's a move away from idealized depictions prevalent in earlier religious art and, even within the Baroque’s theatricality, pushes toward a relatable humanity. Consider the patrons and the viewers of art at the time. What socio-political function might this representation serve? Editor: Perhaps it speaks to a growing merchant class and a desire for art that reflected their own, less overtly aristocratic values and faith. A King showing humility aligns with those values, I guess. Was Rembrandt challenging existing artistic and societal norms? Curator: To some extent, yes. He was certainly catering to a specific segment of the art market in the Dutch Republic, where religious and social values were evolving. And this piece provides insight into how artists negotiated public expectations with their own artistic vision. Does understanding that context change how you view the work? Editor: Absolutely! I now see it less as a simple religious depiction and more as a carefully considered statement about changing social and religious values in 17th-century Netherlands. Thank you. Curator: And understanding this also reveals that what seems “simple” is always steeped in the social, cultural, and institutional dynamics of its time. A valuable reminder!

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

Rembrandt used a print after Rubens as his model for the figure of the kneeling king. The Christ Child, on the other hand, sprang entirely from his unsurpassed powers of observation. In contrast to the stylized, muscular Child, with which he would have been familiar in the visual tradition, here he drew an unmistakeable infant who is still unable to hold up his head.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.