Studienblatt_ Ein Liebespaar, die Frau zupft das letzte Blüttenblatt aus (_Er liebt mich, er liebt mich nicht_)

0:00

0:00

drawing, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

narrative-art

#

figuration

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

line

Copyright: Public Domain

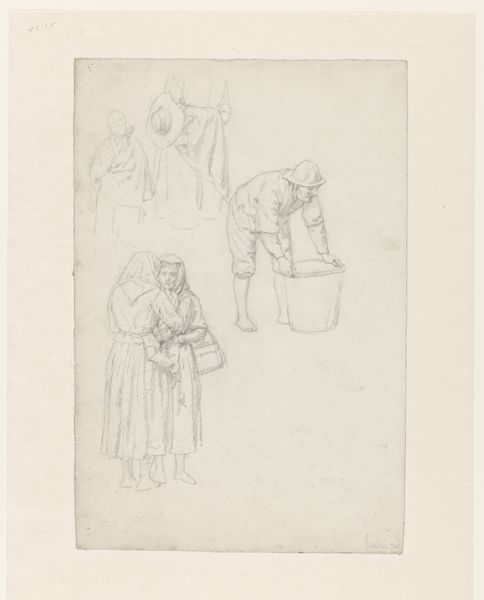

Curator: Here we have a drawing titled "Studienblatt Ein Liebespaar, die Frau zupft das letzte Blüttenblatt aus (Er liebt mich, er liebt mich nicht)", attributed to Gustav Heinrich Naeke, from the 19th century. It's an ink drawing, currently residing here at the Städel Museum. Editor: Immediately, I’m drawn to the fragility of it, almost as if the very act of sketching these figures might cause them to evaporate. Curator: That's an astute observation. The linework, quite characteristic of Romanticism, really lends itself to that ephemeral feeling. The poses evoke classical sculptures but the delicacy, the tentative touch, speaks to the era's heightened sensitivity. What else strikes you? Editor: The way he repeats the couple in different states, like frames in early animation. There's a sort of longing present, definitely a feeling that these people, and possibly the artist too, are in search of something... perhaps a reciprocated love? It makes the little flower game quite sad really. Curator: Yes, the 'he loves me, he loves me not' narrative adds an interesting layer, hinting at the precarity of courtship and the social pressures on relationships in 19th-century society. Notice the man’s attire. The detail indicates some higher standing, yet he too, seems caught in this game of chance. The repetition highlights how such anxieties permeated across social lines. Editor: And doesn’t it still? The desperation in assigning certainty to love via a daisy? It's almost absurd, or endearingly human at least. It also prompts me to consider my own expectations for what romantic fulfillment should look and feel like. It hasn’t changed much, I'm afraid. Curator: These representations reinforced social constructs around love, marriage, and gender roles. Art like this acted as both a reflection and a perpetuation of cultural norms. It becomes a source document illustrating the societal constraints individuals were navigating. Editor: I now view it a little differently; I see more tension there. It's not just gentle longing; it's the anxiety that comes from existing inside those societal restraints. So many flowers were probably harmed in pursuit of answering a scary question! Curator: It certainly reveals more than initially meets the eye. Art provides these access points into past anxieties as it is the present too, but we look through a lense today, which gives us more freedom, or perhaps other anxieties. Editor: Indeed, thank you for pulling the thorns from my flower-powered musings!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.