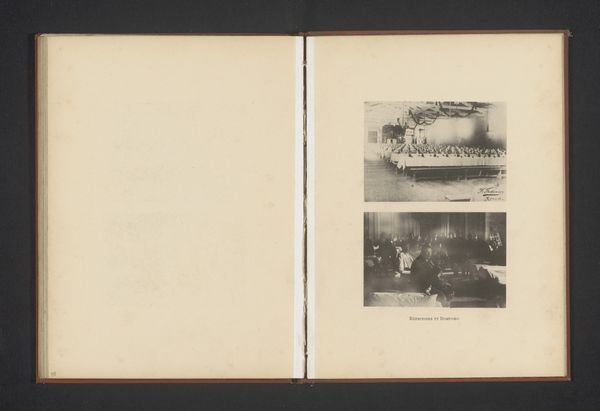

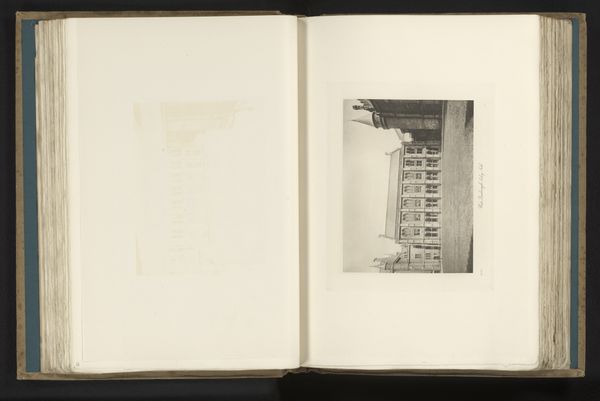

Gezicht op de eetzaal van het kasteel van Loppem in Zedelgem-Loppem, België before 1896

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 110 mm, width 159 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The albumen print before us, attributed to Joseph Casier and taken before 1896, offers us a "View of the dining room of Loppem Castle" in Belgium. Doesn't it feel incredibly still? Editor: Yes, a captivating stillness. The muted tones and the sharp geometry of the room project a feeling of austerity, perhaps even isolation, that contrasts sharply with what one usually associates with the sharing of a meal. Is it simply a recording, or is it more evocative of, say, bourgeois power, with all its implicit codes and constraints? Curator: I believe it functions on both levels. Consider the symbolic weight carried by objects in a dining room. These meticulously arranged bottles and plates act almost like hieroglyphs signifying social standing, tradition, the legacy of aristocracy. The emptiness of the space underscores the performative aspect of dining in such surroundings. Editor: Absolutely. Think of the politics inherent in such carefully designed spaces. The act of consuming, often veiled, is blatantly material here. And if one focuses on the era in which it was shot, it also provides insight into how bourgeois family life at the time operated along complex gendered and social hierarchies. Curator: Furthermore, it invites us to ponder on absence: the absent diners. A traditional space represented by this photograph often served as the theater for the drama of everyday social exchange. Without bodies populating it, our eyes are trained on architectural choices as markers of distinction, even oppression. Editor: Perhaps. It’s hard not to ponder the historical moment of the photographer—Casier—as witness but also an agent complicit in this representation of bourgeois taste. Photography, particularly then, was rarely neutral. Its documentary impulse carried very specific biases. How did that affect marginalized social groups, for example? Curator: It is true that period genre-paintings rarely included working class subjects. These photographs from Loppem, steeped as they are in romanticism, may offer insight into family dynamics within aristocratic circles, their rituals and symbols… Yet it also closes certain doors of perception onto ordinary lives from that same era. Editor: Ultimately, this image functions as both an aesthetic object and a socio-political artifact, speaking volumes about both power and representation. Curator: It's a delicate dance between what is explicitly shown, and what the composition subtly infers about Belgium during the fin de siècle.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.