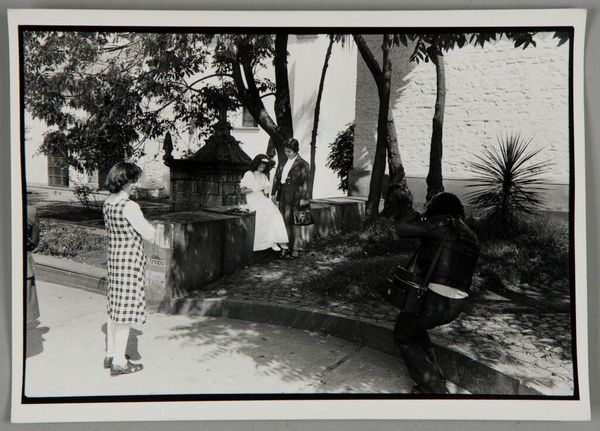

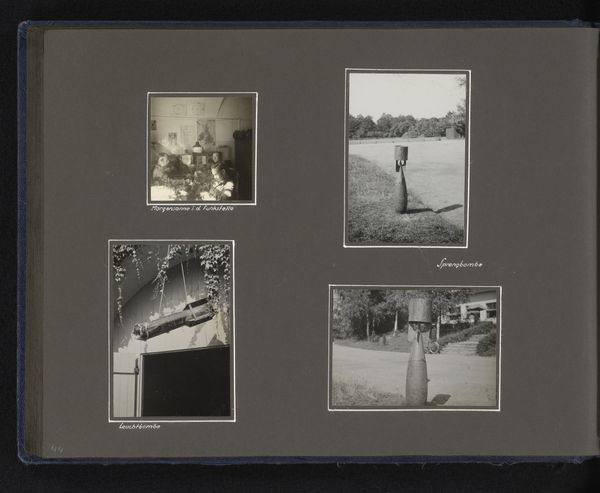

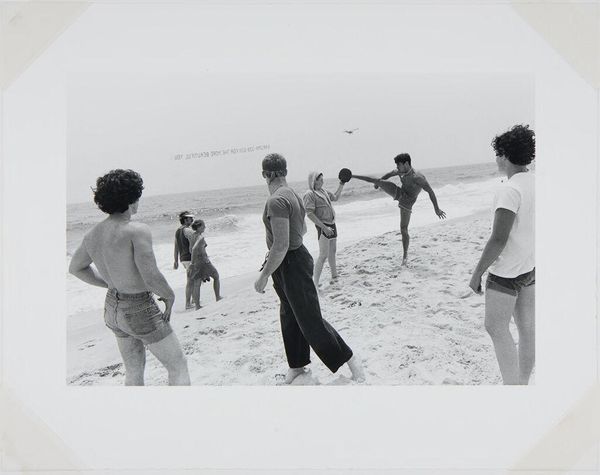

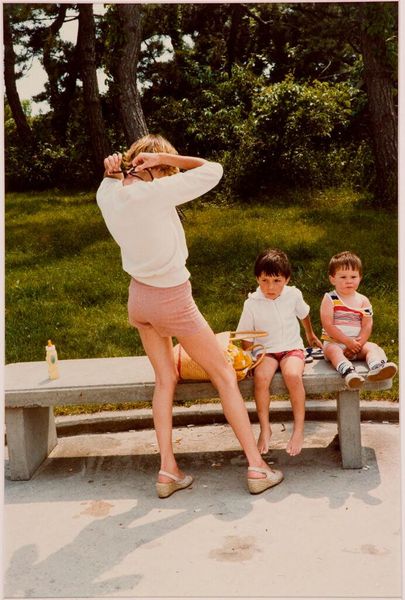

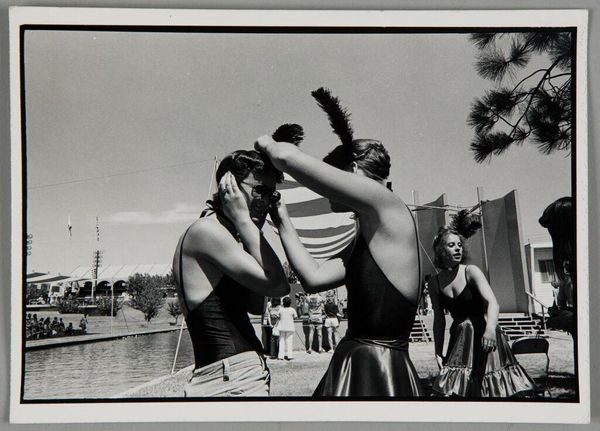

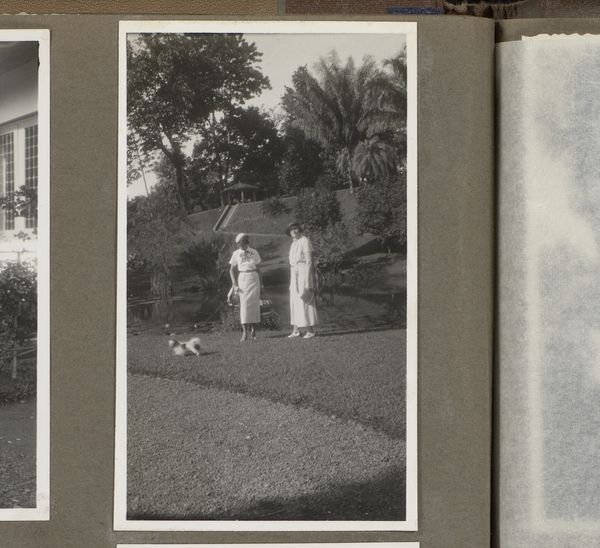

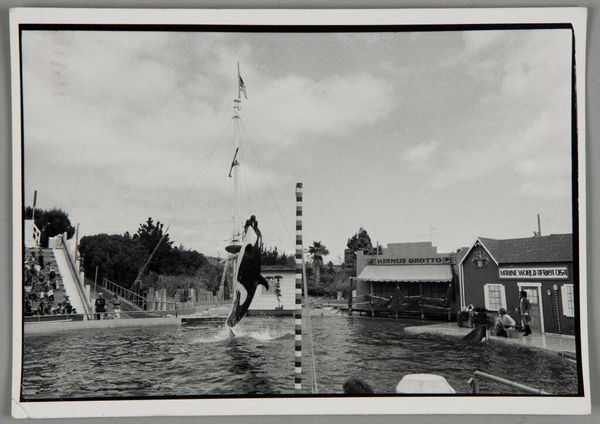

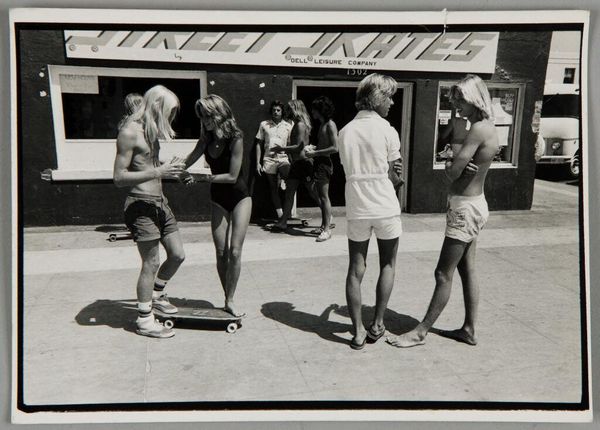

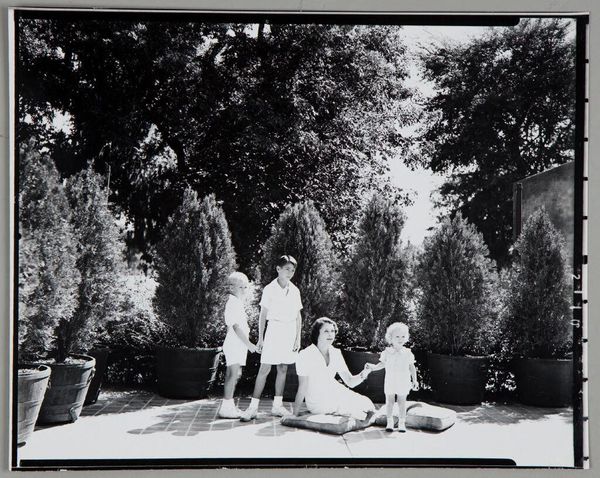

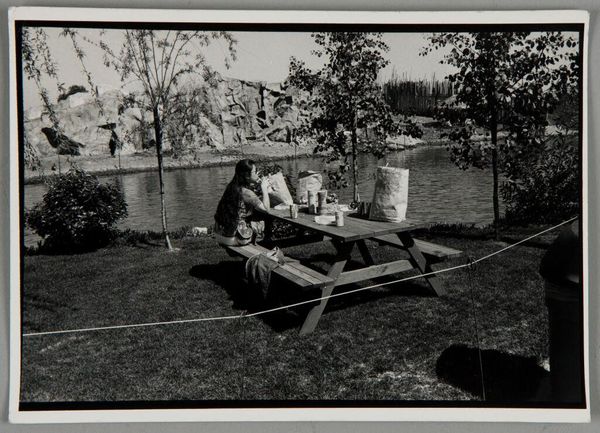

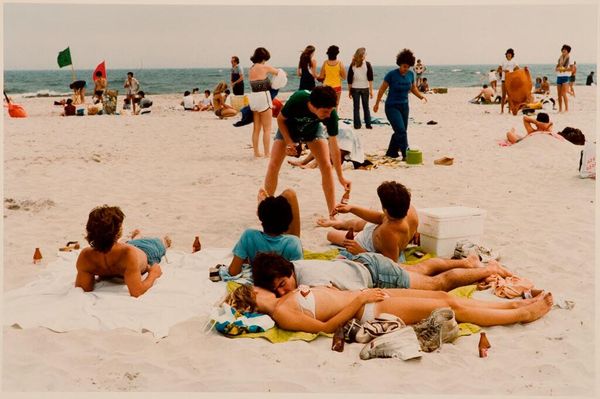

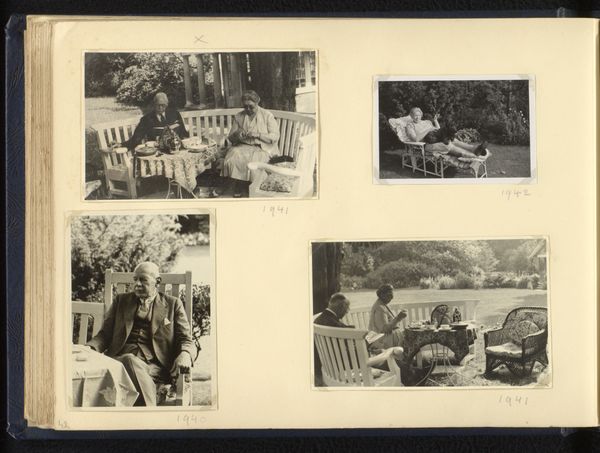

c-print, photography

#

portrait

#

conceptual-art

#

postmodernism

#

c-print

#

photography

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: image/sheet (each): 41 × 53.6 cm (16 1/8 × 21 1/8 in.) framed (each): 42.1 × 54.61 × 3 cm (16 9/16 × 21 1/2 × 1 3/16 in.) overall: 126.3 × 163.83 × 3 cm (49 3/4 × 64 1/2 × 1 3/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

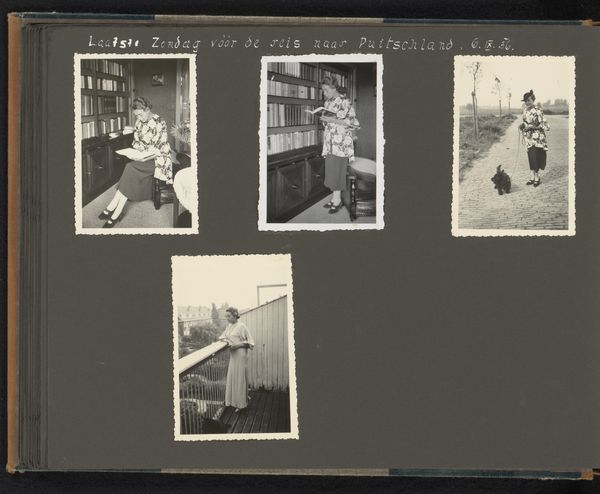

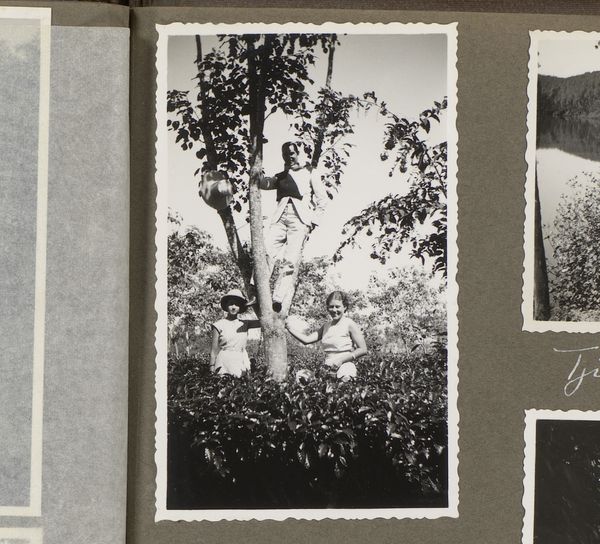

Editor: This is "Nine Stills from My Family's Home Movies" by Larry Sultan, created between 1985 and 1992. They’re C-prints, so photographs essentially, arranged in a grid. It’s… surprisingly melancholic for something depicting such seemingly idyllic suburban scenes. What strikes you about it? Curator: Melancholy is a perfect word. There's a sense of distance, a slight remove, isn’t there? As if we're not just viewing a family's memories, but *examining* them. The mundane elevated, the quotidian…questioned. Those shaky, washed-out colours lend such a haunting air to this work, what I describe to myself as “Ghostly Kodachrome." How do they strike you? Editor: Yeah, exactly! Like…staged nostalgia? They feel intimate but also… performative somehow. It is true: the faded, dreamlike qualities of these snapshots of familiar places or experiences—family vacations, a man cutting the grass in his backyard, playing with the kids—all leave you somewhat unnerved and detached from reality. The colours add to this impression and suggest a feeling of the "good old days.” Is this something you also notice in conceptual art of the 80s and 90s? Curator: Absolutely. It was a time of intense self-awareness, questioning the very nature of representation. Think Cindy Sherman and her constructed identities, for example. The "snapshot aesthetic" was embraced, partly as a reaction against the glossy perfection of commercial photography. It was as if these artists were saying: "Life isn't perfect, memories are flawed, and that's okay. We can make art out of these very imperfect images." I do find a fascinating commentary on the American Dream in this set of photos, with both the reality of day-to-day existence and the construction of a narrative that might not align with actual life, captured for generations through images or home movies. The truth remains elusive. Is that fair? Editor: Definitely fair! Seeing those “behind the scenes” glimpses of what looked perfect, it makes you wonder what's real and what's carefully created. I am going to leave thinking a bit about that duality and the artist’s critical approach of suburban life. Curator: Precisely! That space between what's shown and what's hidden... that’s where the real art happens. The rest, as the say, is commentary.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.