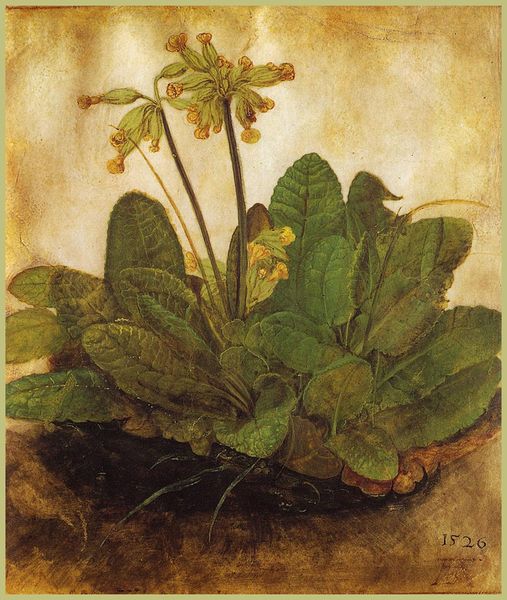

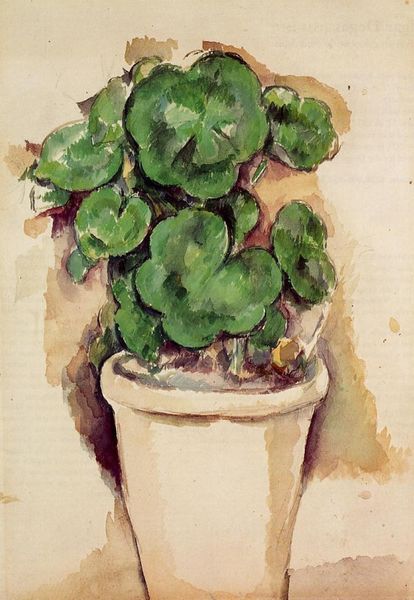

drawing, paper, watercolor

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

oil painting

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

botany

#

northern-renaissance

#

watercolor

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Look at this, an absolute symphony of green! The work before us is Albrecht Dürer's "The Tuft of Grass," rendered in watercolor and gouache on paper, dating back to 1514. Editor: It's astonishingly realistic, isn't it? Almost photographic in its detail. The varying textures of the leaves and stems practically invite you to touch them. It evokes a deep sense of quiet observation, like peering into a miniature world. Curator: Absolutely, and that is no accident. Dürer’s approach marked a pivotal moment in art history, particularly in its engagement with the natural world. While botany held importance in Renaissance understanding of medicine and herbalism, it served also as reflection for that same era’s relationship to capitalism. These were times of intense landscape transformation driven by agriculture; images like this show what the ruling class left to destroy and, by doing so, control nature and people alike. Editor: I agree, especially thinking of Dürer's social position and artistic circle, seeing nature meticulously cataloged like this also makes me a bit uncomfortable because that intense scrutiny isn't apolitical. The level of control embedded in the act of observation… Curator: Exactly. And yet, to his contemporaries, I would imagine Durer was showcasing the beauty of the natural world for a viewing public conditioned only by religion to reject the materiality around them, this to promote an increased social, even spiritual relationship with the world itself. But the "nature" he's so painstakingly rendering would become only an imaginary idyll, or for some perhaps, but the nature he sees here will, shortly after he painted, come under siege through early capitalist modes. It becomes increasingly difficult to find untouched spaces once those modes set the stage. Editor: It truly makes you consider what escapes observation, too. Who determined which plants are worthy of rendering? What voices aren't centered within these archives of detail? Are these perhaps allegorical reflections, mirroring the plight of peasant’s social control who saw his source for food turned from wild plants like these, into mass farmings instead. Curator: Those considerations speak to contemporary critical engagements with history of Northern Renaissance artistic legacy. What were your own take aways then about your encounter with “Tuft of Grass”? Editor: To sum it up, Dürer has once again reminded me of the complicated intersection of power and nature’s role as subject of analysis in art and botanical practice, but always bringing with her an intimate message as reminder to observe without conquering those beings different than we, but that still can be like ourselves . Curator: A powerful note on which to end. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.