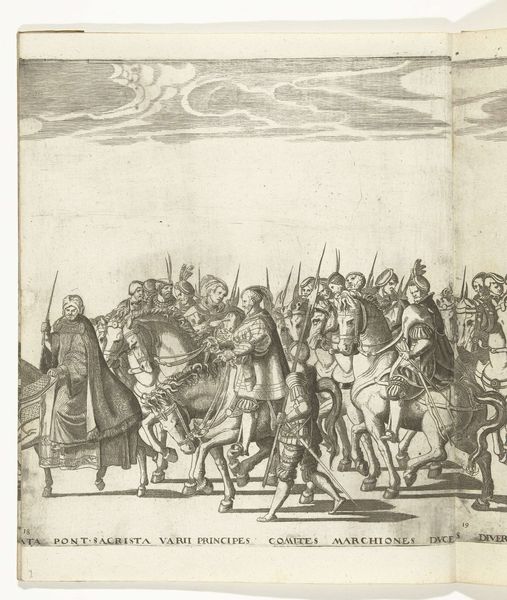

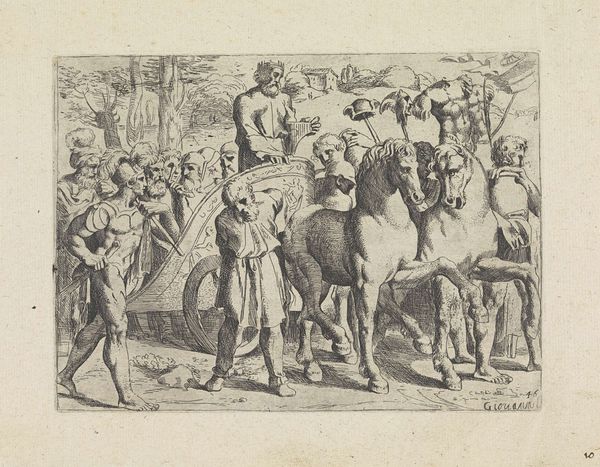

Plate 4: The peace with the king of France in order to fight the Turks, from the Triumphs of Charles V 1614

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

soldier

#

horse

#

men

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: sheet: 11 13/16 x 16 15/16 in. (30 x 43 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is Jacques de Gheyn III's "Plate 4: The peace with the king of France in order to fight the Turks, from the Triumphs of Charles V," an etching created in 1614. Editor: My first impression? An assertion of power through military strength and staged unity. The sheer number of figures—mounted soldiers filling the frame—speaks to the might being projected. Curator: Indeed, Gheyn employs symbolic language throughout. Notice how the horses are rendered. Their raised hooves and proud carriage have historically connoted leadership, triumph, and unstoppable advance. Editor: Precisely. But it's worth questioning who gets to define "triumph" and at whose expense. Here, it’s predicated on a fragile peace treaty, conveniently masking underlying tensions with France, and directed toward what goal? A manufactured ‘us vs. them’ narrative with the Turks. The ‘peace’ enables further aggression and domination abroad. Curator: It's a fascinating point. These processions were designed to project an image of stability and divine right, employing figures rooted in classical antiquity to reinforce their ruler’s lineage and authority. Editor: Yes, this appropriation of Roman imagery seeks to legitimize political power. Even the laurel wreaths suggest an inherited, rightful claim to power, despite the unstable foundations upon which it rests. It feels so performative! Curator: But perhaps that performance is the key. The symbols resonate with a shared cultural memory, crafting a narrative palatable to the populace, even if the reality is more complicated. Consider, for example, the significance of the double-headed eagle; what might that invoke within an audience steeped in symbolist ideology? Editor: Definitely a deliberate choice. While on the surface, it could imply a connection to Imperial Rome, I find it ultimately points to an empty promise of strength via militarized performativity. De Gheyn exposes it! Curator: This piece offers so much in terms of exploring how rulers manipulate and disseminate images to bolster power. Editor: Exactly, seeing through those projected illusions encourages us to examine how such tactics persist in our own world. The image might depict a truce, but the real battles for freedom are for sure ongoing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.