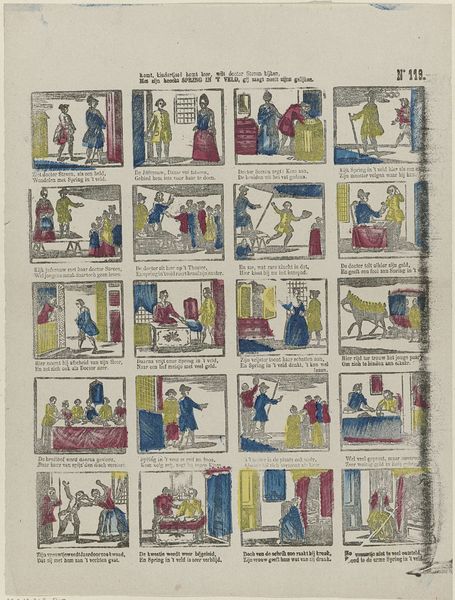

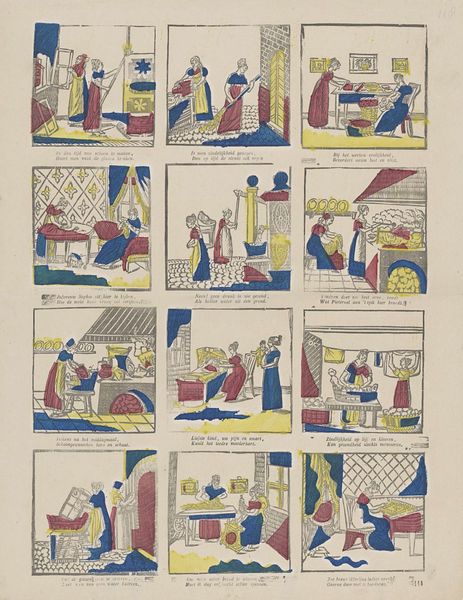

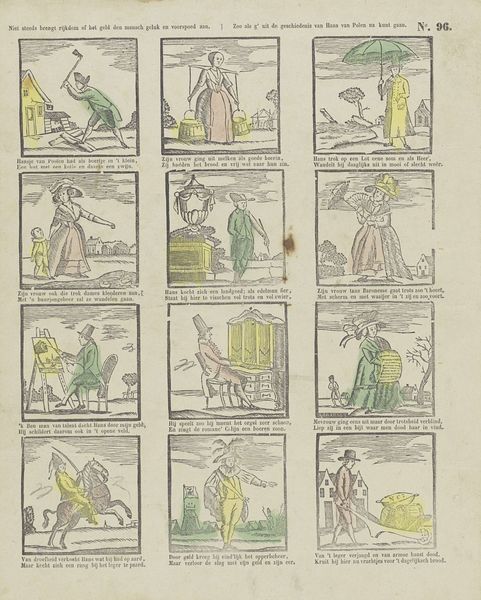

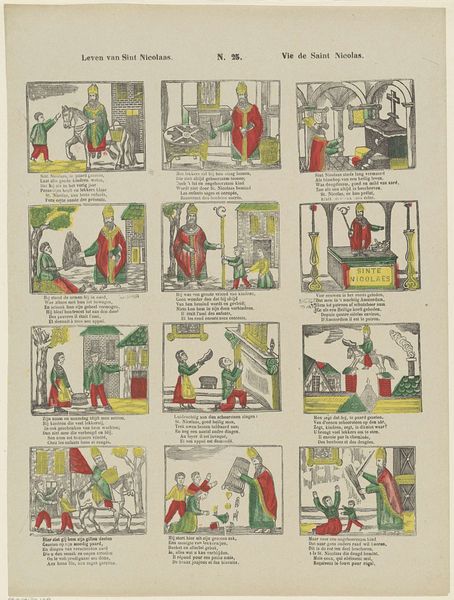

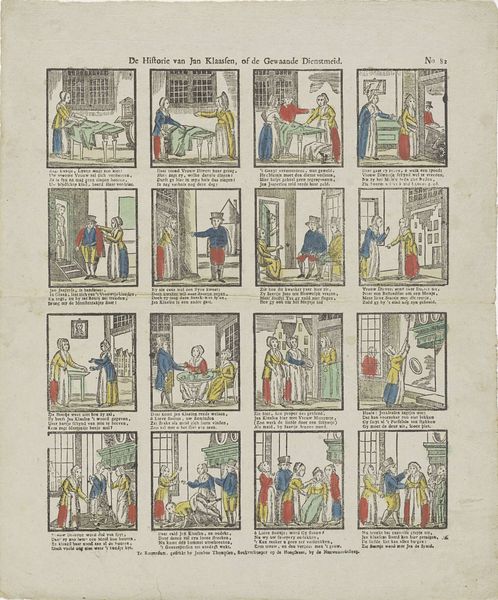

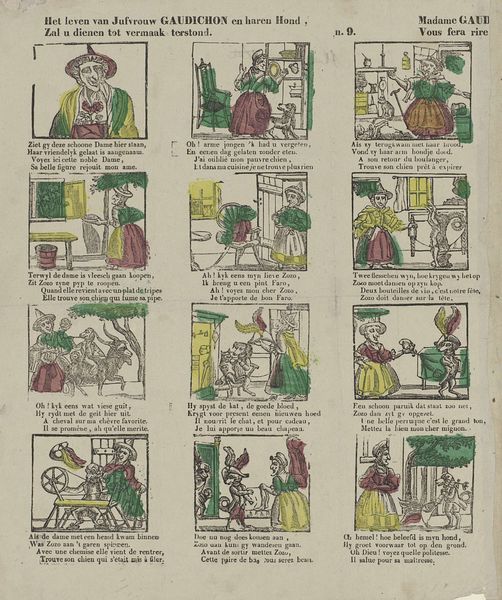

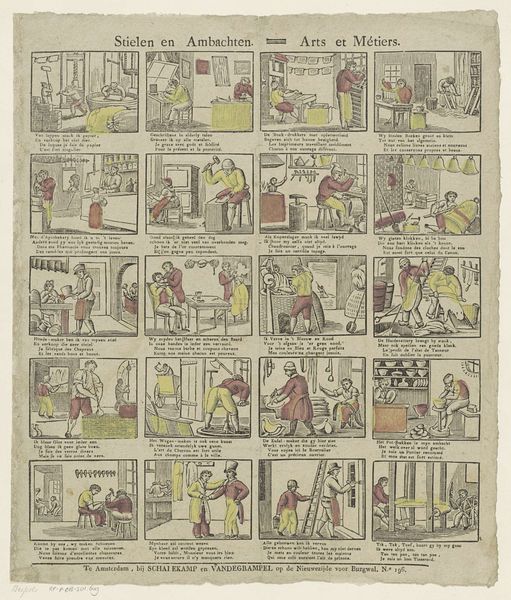

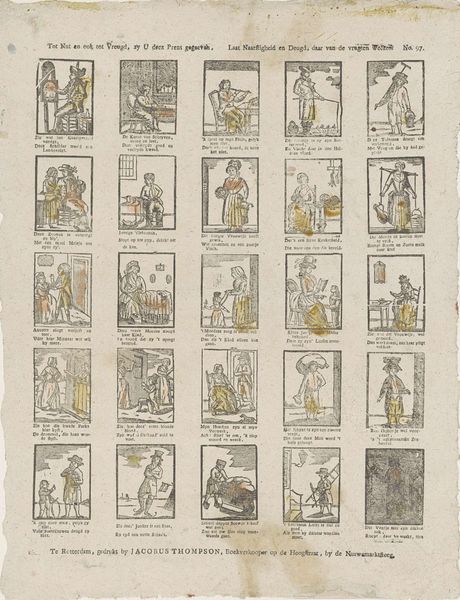

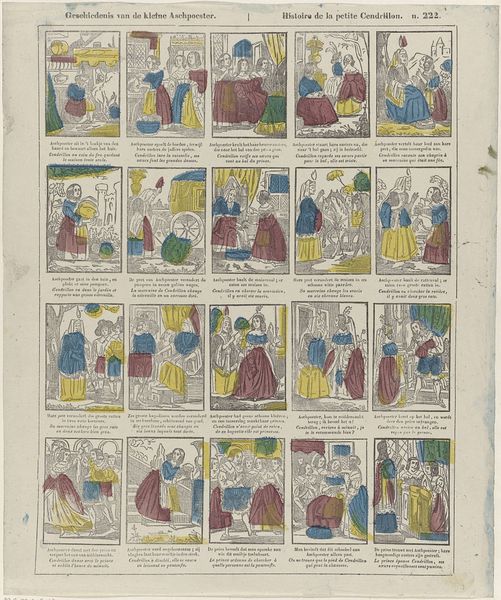

Leert kinderen, uit deez' prent u altyd wel gedragen, / En volgt geen boozen na, maer blyft op 't pad der deugd. / Dan zult gy 't allen tyd aen ieder mensch behagen, / Dan snelt de tyd voorby in innerlyke vreugd 1833 - 1900

0:00

0:00

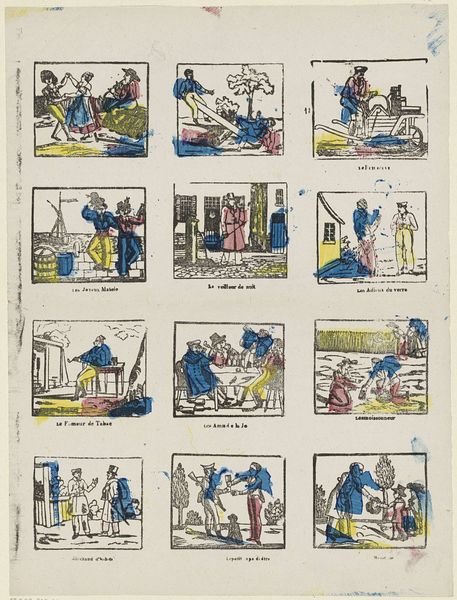

graphic-art, print, woodcut

#

graphic-art

#

comic strip sketch

#

narrative-art

#

comic strip

# print

#

folk-art

#

woodcut

#

comic

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 396 mm, width 344 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This narrative woodcut, titled "Leert kinderen, uit deez' prent u altyd wel gedragen, / En volgt geen boozen na, maer blyft op 't pad der deugd. / Dan zult gy 't allen tyd aen ieder mensch behagen, / Dan snelt de tyd voorby in innerlyke vreugd" created sometime between 1833 and 1900 by Glenisson & Zonen, offers a series of domestic vignettes. My immediate impression is how orderly, if slightly quaint, this world appears. Editor: Quaint, yes, but orderly tells another story. Look at the repetition of gestures, the careful positioning of figures within each frame. Doesn't it feel less like domestic bliss and more like a scripted performance of social expectations? Curator: Certainly! Consider the inscription, a direct address urging children to "always behave well" and avoid evil. The woodcut, reproduced as a print, functions didactically, disseminating bourgeois values regarding labor, family, and childhood across 19th-century Dutch society. These weren't just innocent scenes, but potent tools of cultural formation. Editor: Absolutely. We see symbols reinforcing moral instruction everywhere: children assisting elders, women at work indoors—the implied blessings for virtuous behaviour. And even the colour palette carries this weight; the consistent use of certain colors signifies particular actions. Curator: It raises a provocative question: How effective was this form of visual moralizing? And what alternative narratives were available to challenge its authority? We might see the work and assume all dutifully heeded it's message but perhaps we should see the images themselves as symbolic acts of desire and aspiration for different viewers, many unable to attain such standards and lifestyles? Editor: Yes. We can imagine it being consumed differently by different segments of society, with very specific power relationships inscribed through repetition of gestures and symbols that make particular behaviour easier and harder to imitate based on lived circumstances. This piece embodies what Stuart Hall termed, encoding and decoding. Curator: I’ll leave contemplating these social frameworks with a new appreciation for how these humble prints became arenas where cultural identities and values were not only pictured but were created, resisted and reinforced. Editor: Agreed. Considering visual storytelling not as neutral documentation, but instead as instruments wielded in the making and solidifying of a society—that transforms how we consider pieces such as this.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.