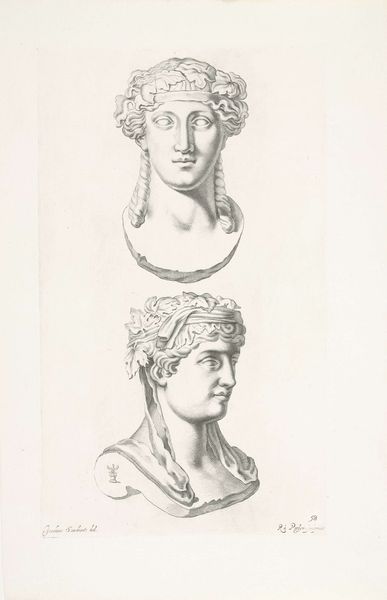

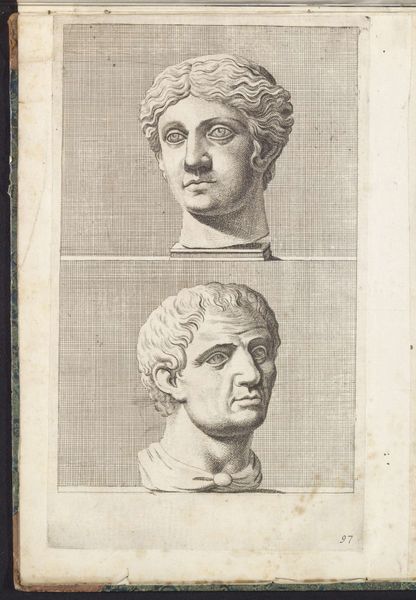

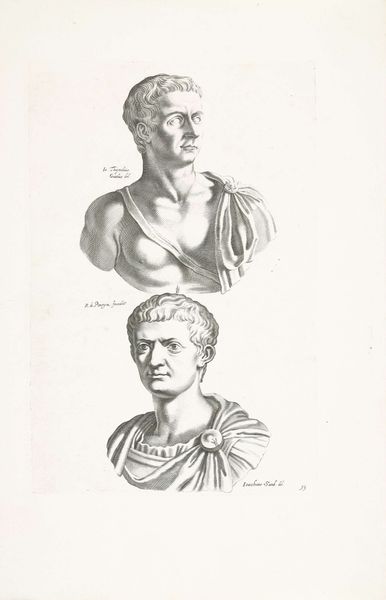

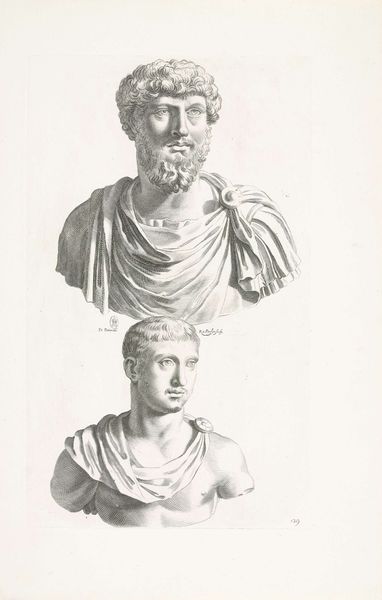

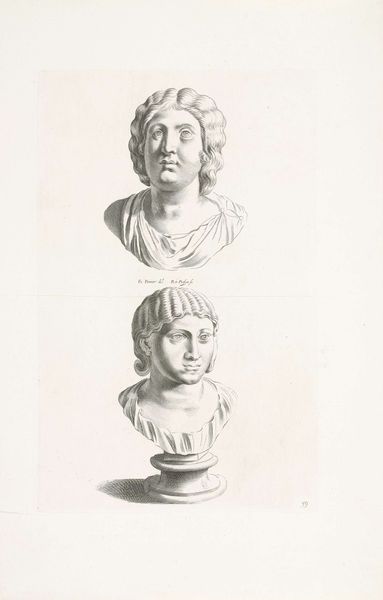

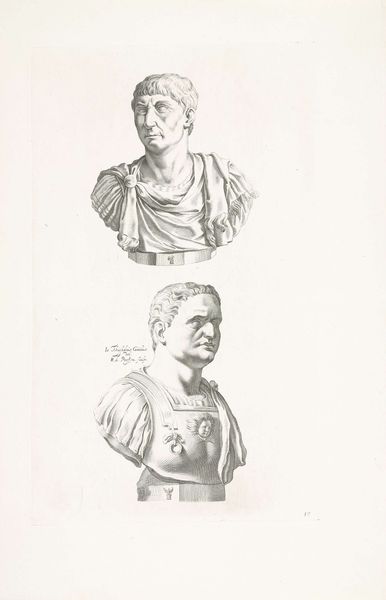

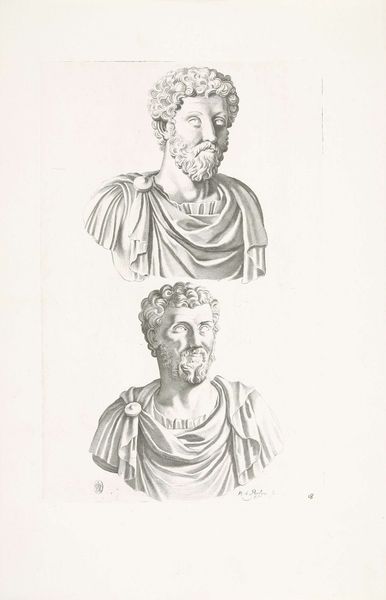

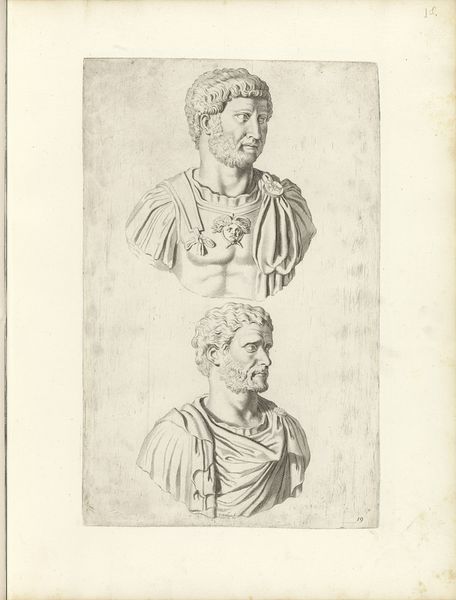

Twee portretbustes van keizer Domitianus en keizer Tiberius 1640

0:00

0:00

reiniervanpersijn

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 368 mm, width 238 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This striking engraving from 1640, titled "Twee portretbustes van keizer Domitianus en keizer Tiberius," brings the visages of Roman emperors to life. It was crafted by Reinier van Persijn and resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The immediate impact is… austere. The sharp lines, the classical realism – it evokes a sense of power, but also of immense distance. They feel less like individuals and more like archetypes. Curator: I agree; the very nature of rendering busts invites archetypal readings. Each carefully etched line around the face carries centuries of symbolic baggage. Note the distinct hairstyles. The upper bust, Domitian, features a cascade of curls which, at the time, was used to denote vigour and strength, something central to his imperatorial role. Editor: Right, and consider how a 17th-century audience would have interpreted this. The Netherlands was establishing itself as a new republic, consciously mirroring aspects of the Roman Republic in its civic identity. Reproductions like this one reinforced that cultural link and conveyed desired virtues. It becomes more than a portrait, really; it is a mirror reflecting and shaping a nascent nation. Curator: Absolutely, especially within the context of Neoclassicism, where these portraits tap into and recirculate a cultural memory. Tiberius’s cropped hair communicates restraint, while Domitian’s connotes an excess— perhaps meant to be seen in parallel to moral debates happening then, using Roman symbolism as guidance for a growing cultural identity in the Dutch Republic. Editor: I’m struck, too, by the subtle choice to present these images stacked vertically. It quietly reinforces a hierarchy and chronology, but more compellingly, suggests these powerful figures were meant to represent how history impacted later generations. Did people consider the historical legacy, as well as the immediate aesthetics, I wonder? Curator: I believe so. Printmaking played an essential role in the dissemination of knowledge, and images like these were accessible. So, although these figures existed long before Van Persijn and his contemporaries, their visual power lived on and allowed these engraved likenesses to educate, inspire, and shape new dialogues on social mores. Editor: Yes, and from a cultural standpoint, observing these ancient portraits allows one to meditate on the very nature of leadership, authority, and remembrance across disparate eras and evolving norms. Curator: Precisely; a print meant to recall the past provides pathways toward picturing and interpreting the future.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.