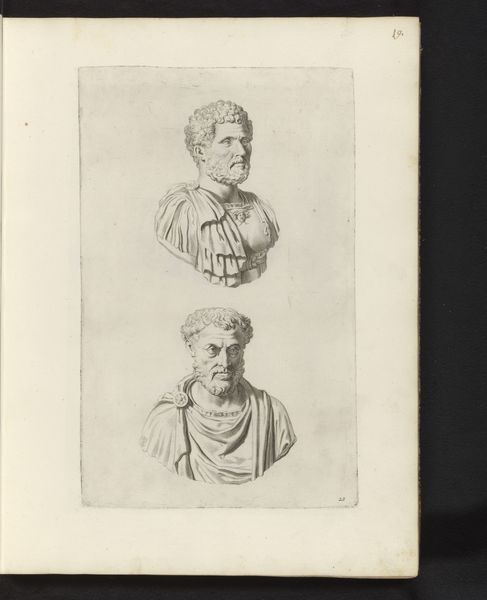

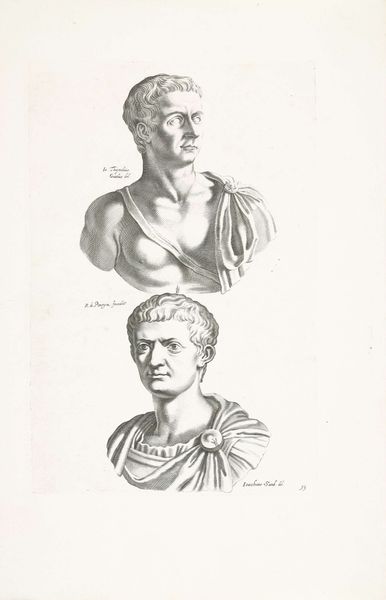

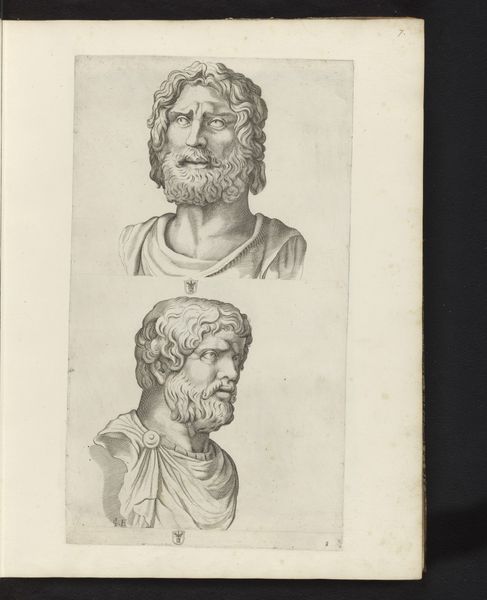

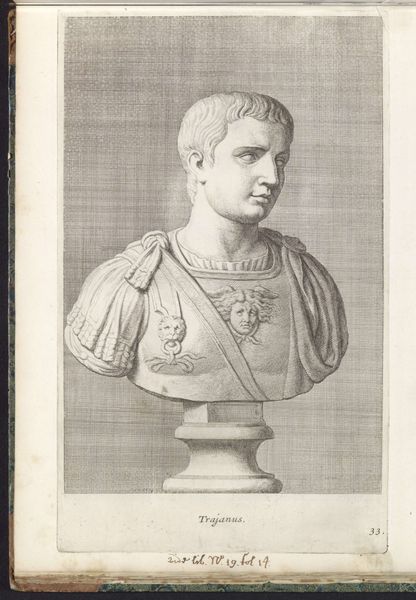

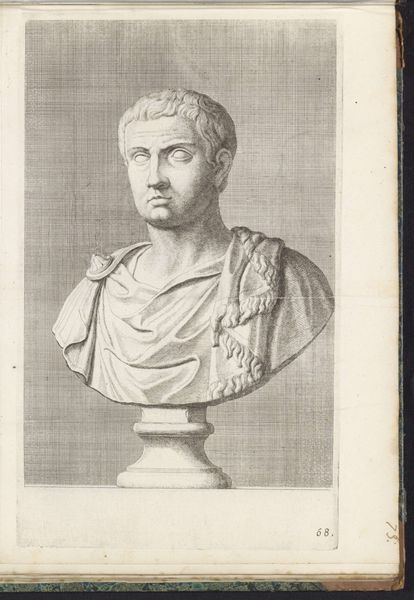

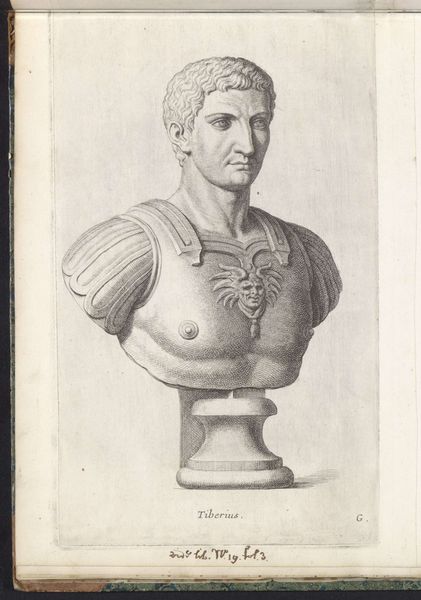

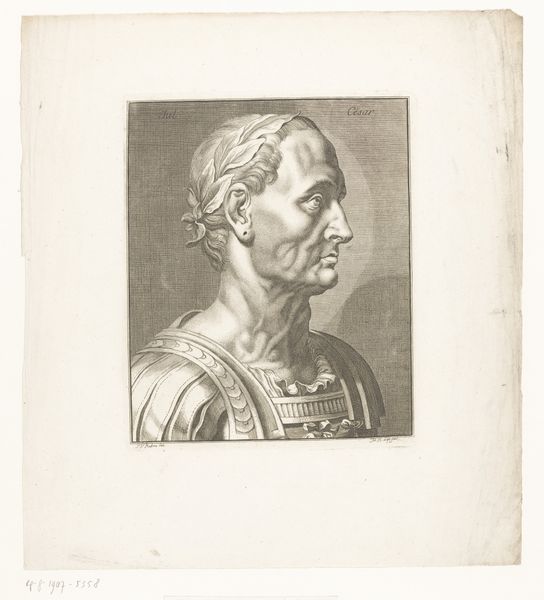

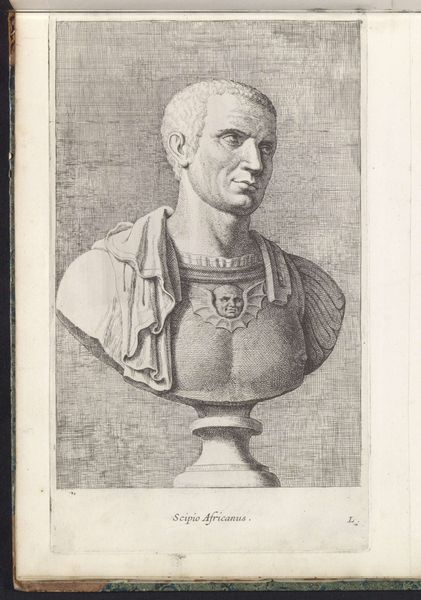

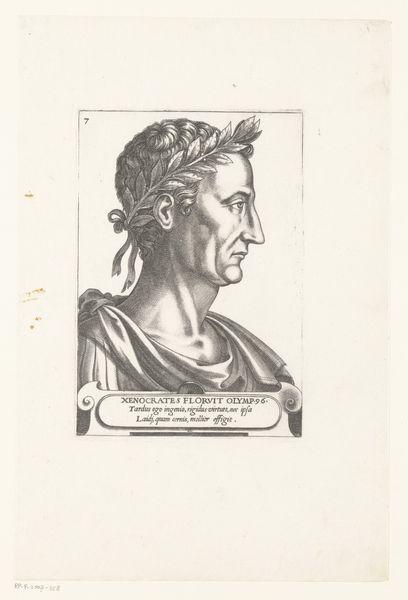

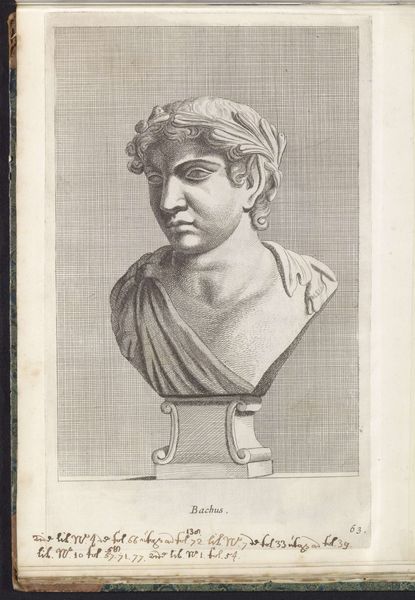

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

geometric

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 370 mm, width 235 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: So, tell me what catches your eye about this engraving, "Bustes van Hadrianus en Antoninus Pius" made between 1636 and 1647 by Theodor Matham. Editor: Well, the contrasting textures achieved just with line, it’s remarkable! Two Roman emperors rendered so precisely… but it's interesting it was made so long after their reigns. What can you tell me about why Matham might have created this piece, centuries later? Curator: Good question! This is more than just a reproduction. Consider the materiality of printmaking itself in 17th century Europe. These images served a growing market for knowledge. Prints facilitated the circulation of Antiquity. It became more widely accessible through mass production. Engravings, specifically, held prestige – their intricacy demonstrated skill, transforming even "historical paintings" into commodities. Editor: So, it’s less about honoring the emperors directly, and more about the culture of replicating and consuming knowledge? Like an early form of accessible documentation through reproducible media. Curator: Exactly. Who controlled those means of production then? Who benefited from making these classical figures accessible? Who could afford to acquire the final prints? It wasn't just about historical appreciation, it's tied to systems of patronage, class, and the economics of art production. It democratizes imagery, yet the access to art production and distribution wasn’t democratic at all. Editor: That's a really interesting way to think about it. Seeing this less as art about Emperors and more as a statement about access and the distribution of power through material reproduction. Curator: Precisely. And by thinking of art objects in such way, we may look into the true underlying nature of art itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.