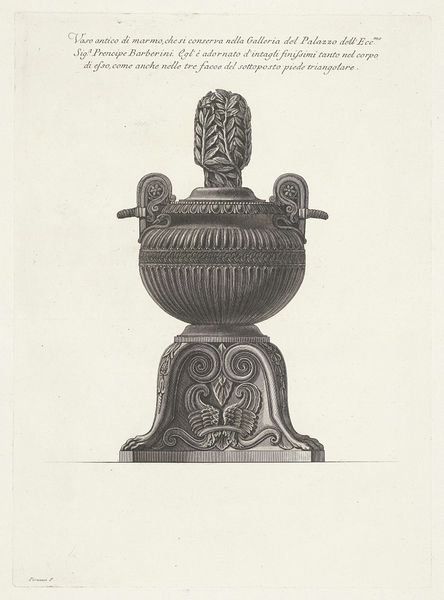

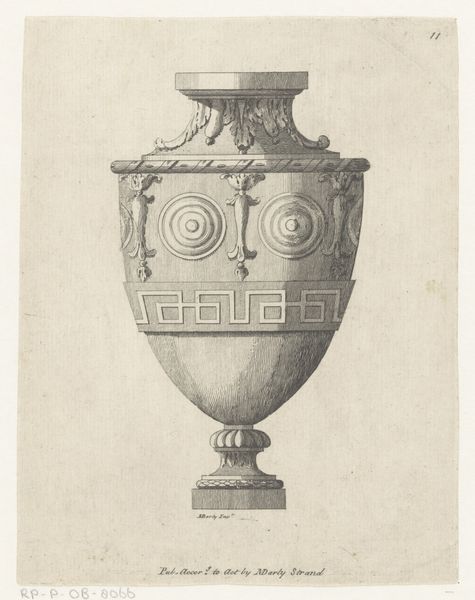

Dimensions: height 527 mm, width 386 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have Piranesi’s “Vaas,” from 1778. It’s an engraving, and what really strikes me is the incredible detail he achieves with such a rigid medium. How do you even begin to interpret something like this? Curator: The first thing that grabs my attention is the sheer labour embedded within its production. Engraving isn’t just about artistic skill, it's about time and dedication to a repetitive physical process. Think about the engraver's hand, guiding the burin, the deliberate removal of material. Does that not make you question what Piranesi intended to communicate about value? Editor: I guess I hadn't thought about it that way, seeing the work more as artistic expression, rather than manual labour. Curator: But where does artistic expression begin and manual labor end? This engraving meticulously documents an object. Marble wasn’t cheap. Consider the social context. Who commissioned these vases? Who had access to them? And who benefited from the labour that extracted the marble, shaped it, and ultimately, this engraving itself? Editor: It makes me reconsider the print as less of a standalone artwork, and more like a record of production. How it exists in a network of making. Curator: Precisely! It blurs the lines between document and art. Its aesthetic value can be re-evaluated based on our awareness of materiality, and its relation to systems of patronage, commodity and craft. It goes beyond a pretty picture and speaks volumes about eighteenth-century society. Editor: It really challenges the traditional definitions we ascribe to art. Thanks; I’m definitely seeing it with new eyes. Curator: Exactly! And that awareness can extend into our appreciation of more art in the gallery.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.