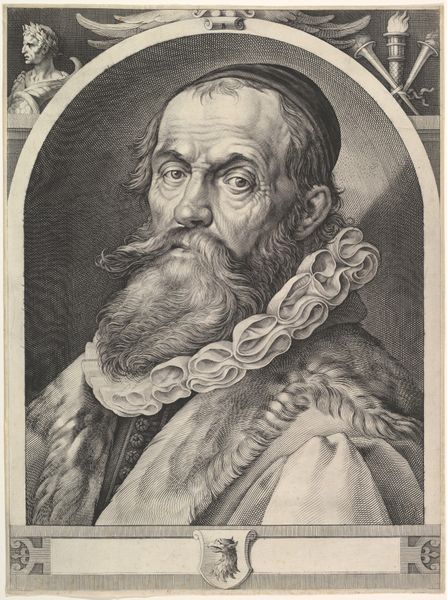

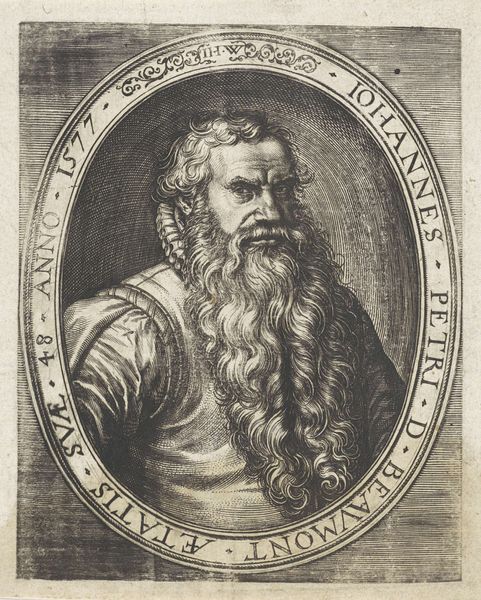

print, intaglio, engraving

#

portrait

#

medieval

# print

#

intaglio

#

portrait reference

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 160 mm, width 126 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving by Wierix, predating 1600 and now housed in the Rijksmuseum, presents us with a portrait of Wilhelmus Boonaarts, also known as Fabius. My immediate response is that of confrontation; his gaze is quite direct, almost accusatory. And the skull…it's quite a striking, unsettling element. Editor: I agree. There's a starkness, an unyielding directness in his posture and the intensity of his gaze, amplified by the monochromatic nature of the print. But I see the skull less as unsettling and more as a statement. This was a period of great intellectual and religious upheaval; perhaps the skull represents mortality in the face of humanist philosophy? Curator: Exactly! Contextualizing this piece, the symbols aren't randomly placed; there's purpose in everything. Look above; the image includes Latin script along with allegorical devices like a globe, figures with wings, and what appears to be an image of a crest. Everything contributes to portraying this man. How do you think the social and political currents of the late 16th century affected the portrayal of scholars? Editor: Well, the rise of printmaking allowed for a wider distribution of images and ideas. So, portraits of learned men like Boonaarts, distributed as prints, helped construct a public image, celebrating intellectual achievement. Think of it as a carefully constructed form of branding – connecting individual fame with virtue and knowledge, which then, I assume, links to the influence held by these scholars and by association their fields of expertise and patrons. I suspect also that this is an attempt to show their dominance during a period of uncertainty, the presence of the skull possibly being to show Fabius’ awareness. But why make a printed edition versus a painting? Curator: Access. It’s critical to remember that paintings of such prestigious individuals would be exclusively viewed by wealthy art collectors, nobles, royals, or wealthy institutions that were interested in projecting power. In that light, who do you suppose the message inscribed at the bottom would have been intended for? Editor: Given Wierix's technical skill in engraving, evident in the fine lines and textures, and the relatively broad dissemination of prints during the period, it becomes evident how effectively these portraits reinforced and upheld the period's rigid social structure and cultural values. He wasn’t merely copying images, but in reinforcing those images and what they represented as truth. Curator: Yes. By understanding the printmaking industry of the time, as well as reading between the lines (literally) to discern underlying societal standards, our comprehension is increased beyond surface level, which is a lesson everyone should take to heart when viewing historical artifacts. Editor: A compelling reminder that art, even portraiture, serves as a lens through which we examine and question power and the status quo, hopefully for generations to come.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.