Dimensions: object: 1264 x 3075 x 90 mm, 588 kg

Copyright: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

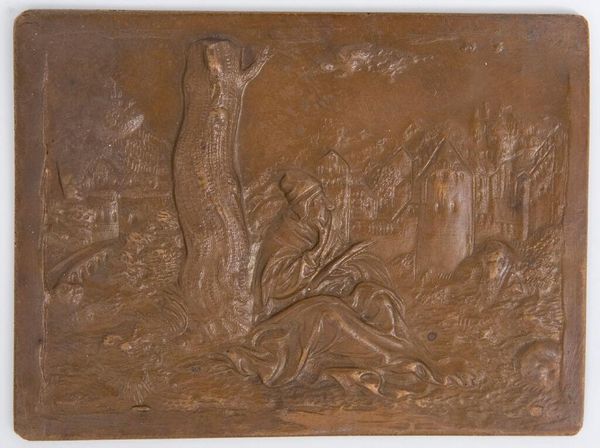

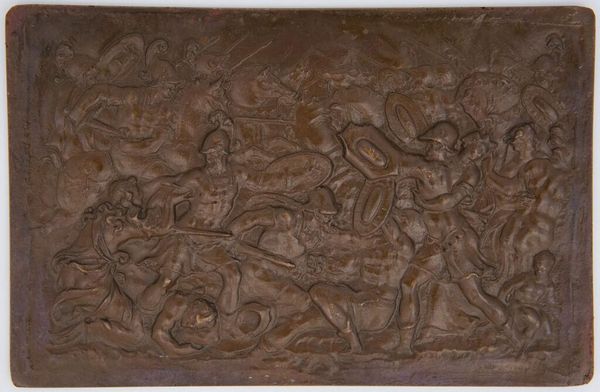

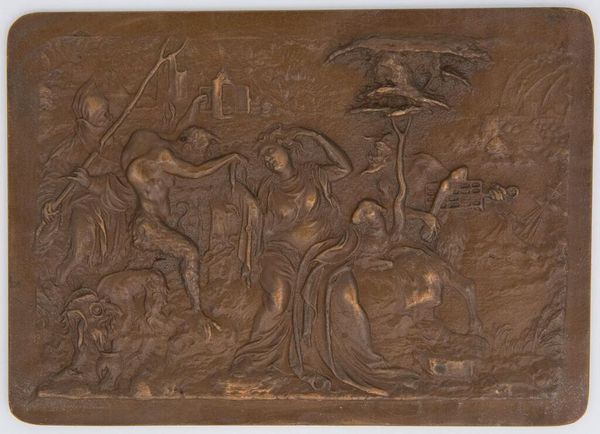

Editor: This is Charles Sargeant Jagger's *No Man's Land*, a bronze relief panel. The scene is clearly one of conflict and devastation. How do you interpret this depiction of war? Curator: It speaks to the brutal reality of war, moving beyond mere displays of heroism to confront its devastating impact on the human body and psyche. What narratives about masculinity are being challenged here, do you think? Editor: It’s as though the traditional glorification of war is being directly contested, focusing instead on vulnerability and loss. Thanks for giving me a new lens. Curator: Precisely. Art can be a powerful form of cultural critique, interrogating dominant narratives and giving voice to marginalized experiences. I'm glad we could explore this piece together.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

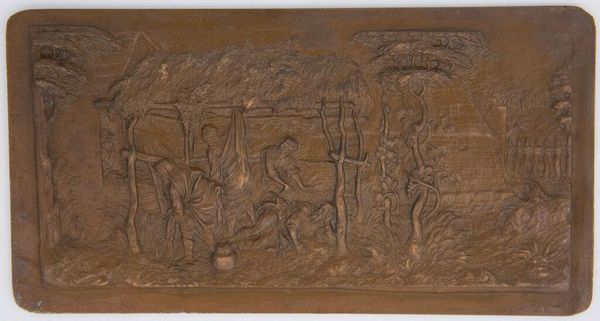

There was an enormous output of memorial sculpture in the early 1920s as every community sought to raise a memorial to the men and women they had lost in the First World War. These ranged from representations of traditionally heroic soldiers to simpler, more abstract forms that acknowledged, perhaps, the unspeakable qualities of the war. The most famous was the Cenotaph, designed by Edwin Lutyens, in London’s Whitehall. Jagger became one of the leading memorial sculptors. Here he shows a listening post in No Man’s Land, where a soldier hides among the bodies of his dead comrades in order to listen to the enemy close by. Gallery label, September 2016