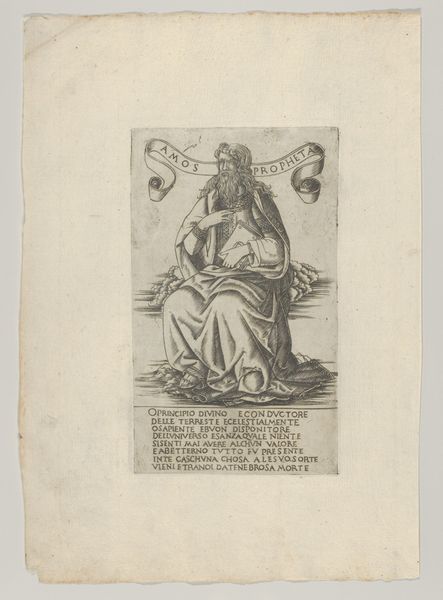

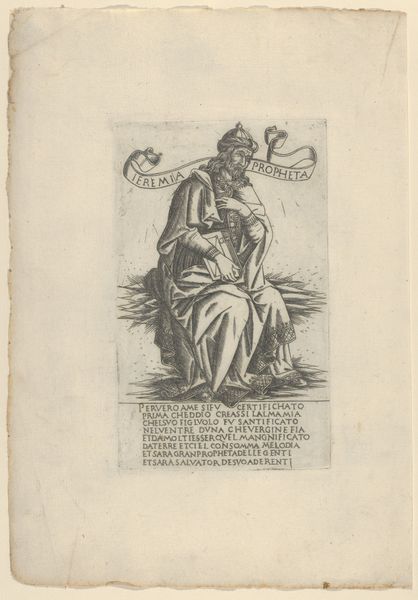

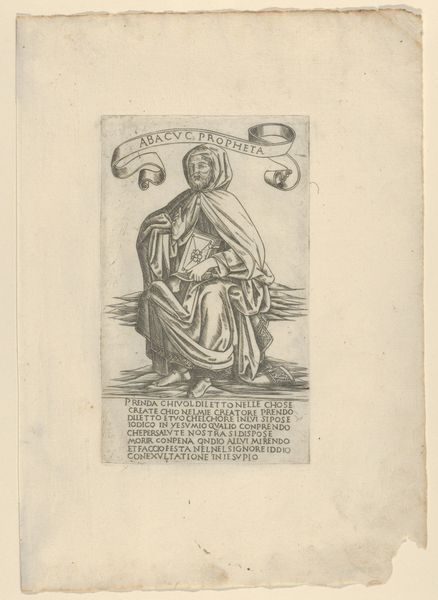

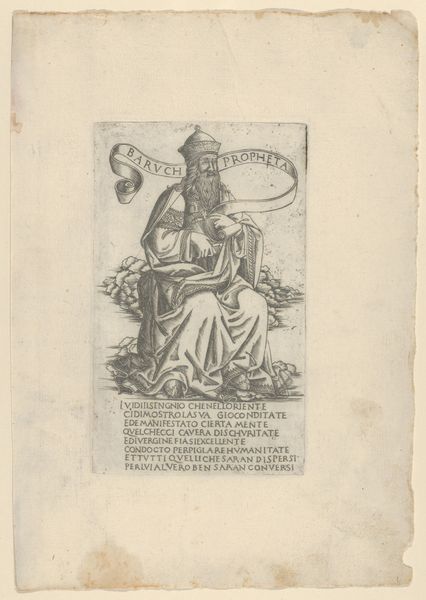

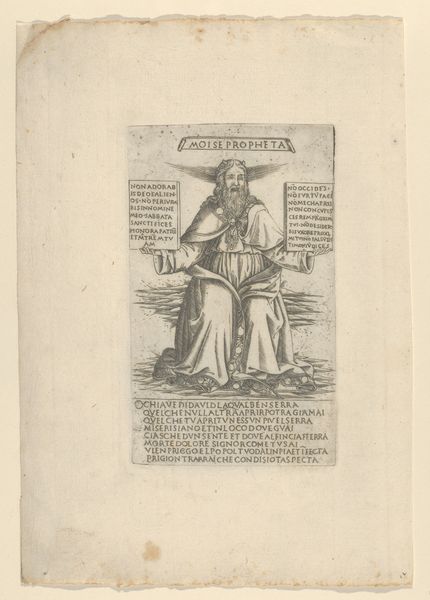

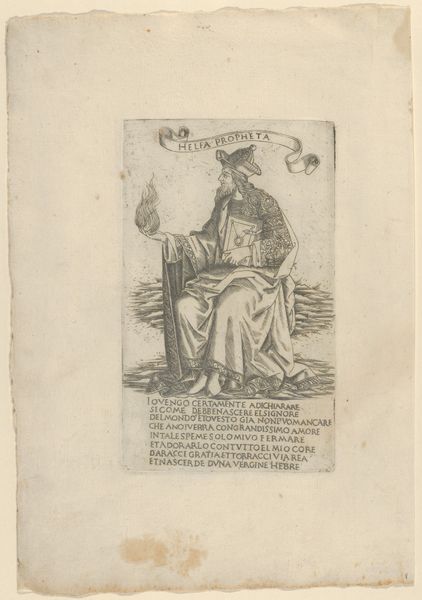

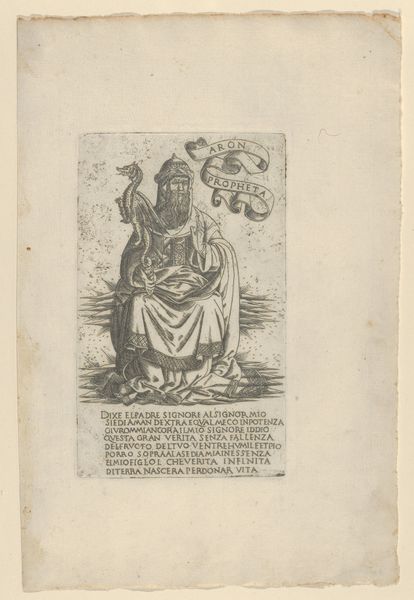

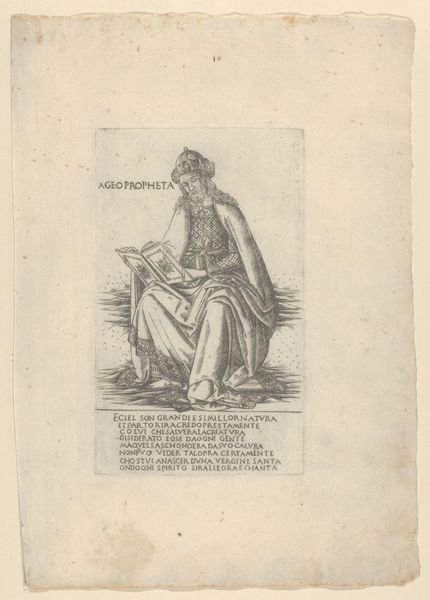

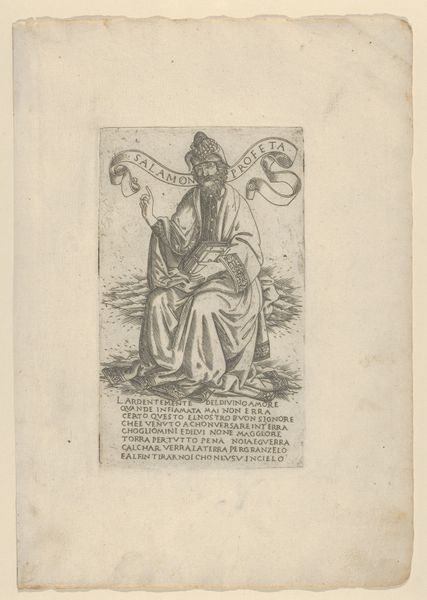

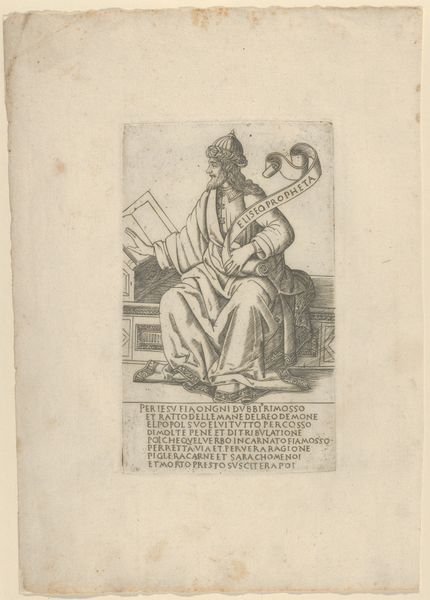

The Prophet Jonah, from "Prophets and Sibyls" 1480 - 1490

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

prophet

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: Sheet: 11 1/2 × 8 1/16 in. (29.2 × 20.4 cm) Plate: 6 7/8 × 4 1/8 in. (17.5 × 10.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

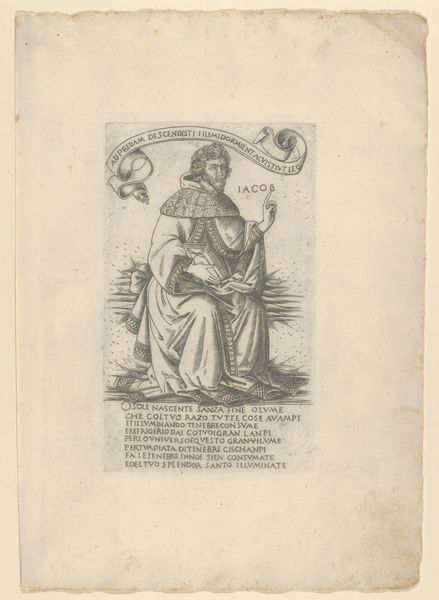

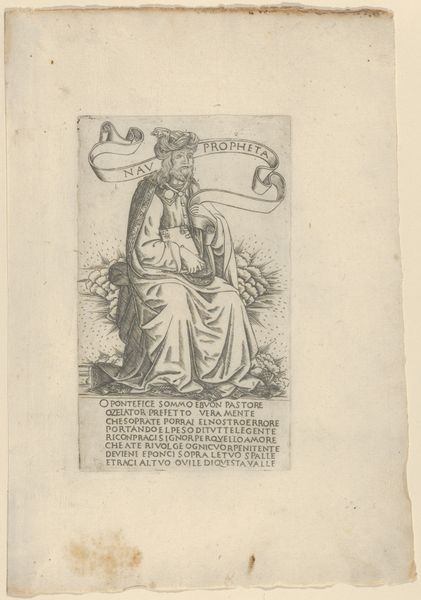

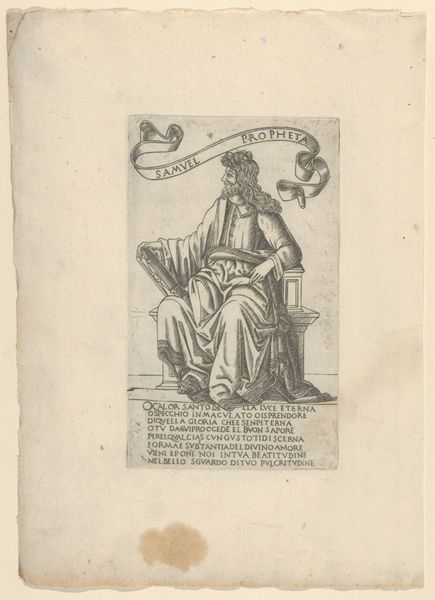

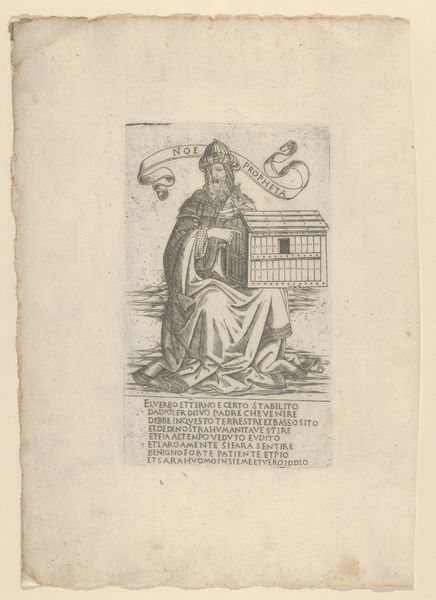

Curator: Look at the detail in this print, "The Prophet Jonah, from Prophets and Sibyls," made between 1480 and 1490 by Francesco Rosselli. It is currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The etching showcases Jonah seated, with the beast that swallowed him presented alongside. Editor: My first impression is one of intricate miniaturization, even fragility. You can feel the labor embedded in that level of detailed rendering of each fold in the robe and scale on the fish. What statements about power were possible with these works? Curator: I am interested in the act of labor, and specifically its accessibility in printmaking during this time. Producing a detailed etching like this would involve skill but also time—a very material consideration. How the finished object then circulated also dictated audience and reach, not just for the art itself but also the narrative that Jonah represents. Editor: Exactly, and thinking about this circulation we must recall the political backdrop of 15th-century Italy, which would’ve colored interpretations of the Jonah story. Remember the corruption within the church at the time. This etching of Jonah gains potency when viewed as a commentary on power, obedience, and divine justice. What sort of social message does it contain for the Italian public of the time? Curator: The materials themselves were increasingly available due to burgeoning trade networks. Copper, inks, paper—the inputs necessary were expanding access, perhaps incrementally democratizing art-making outside traditional workshops controlled by elites. This also facilitated a visual language which promoted dialogue with the stories and morals offered in religion. Editor: I think it’s a fascinating conversation to consider that the means and medium itself had inherent influence in shaping what these narratives represented and ultimately achieved, both then and in our present encounter. Curator: Indeed, seeing the work, understanding the history that impacted its material form, reveals more than an aesthetic impression of beauty, but of artistic agency.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.