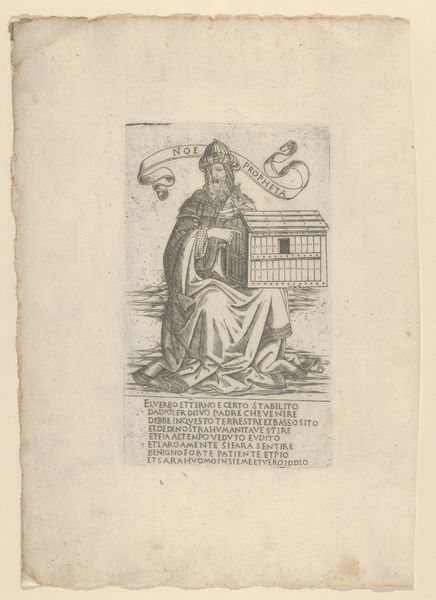

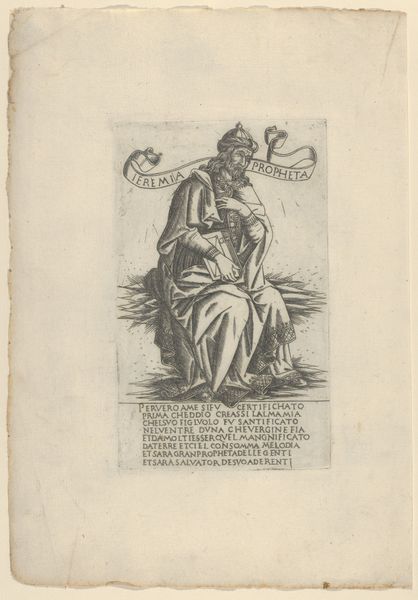

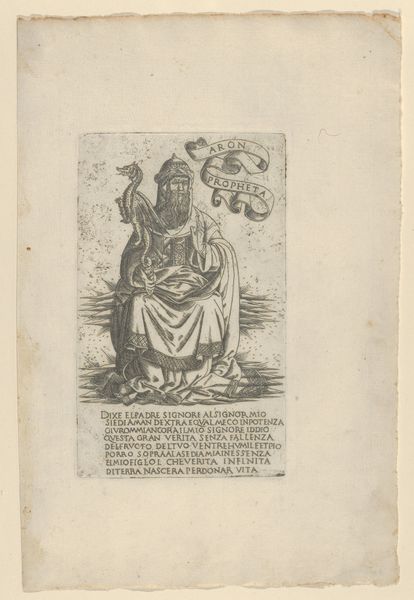

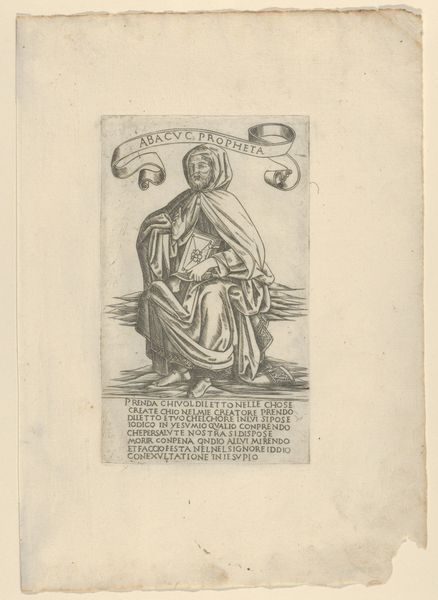

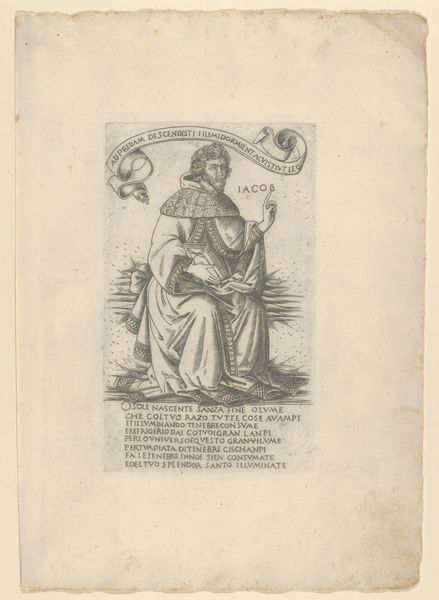

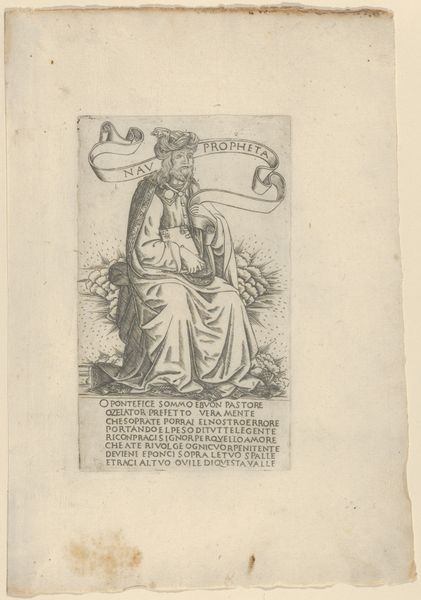

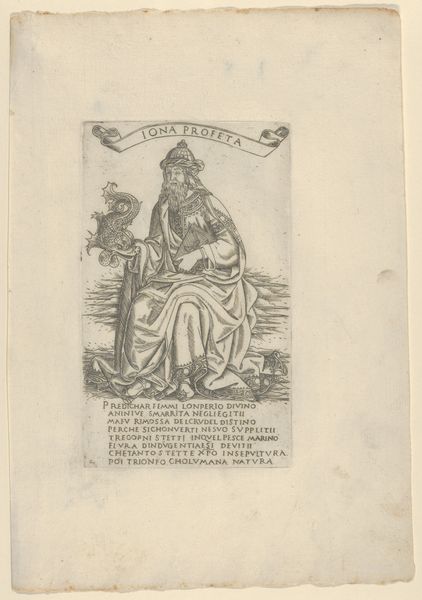

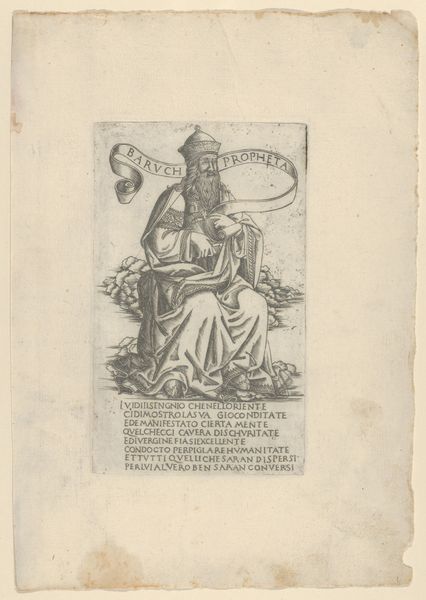

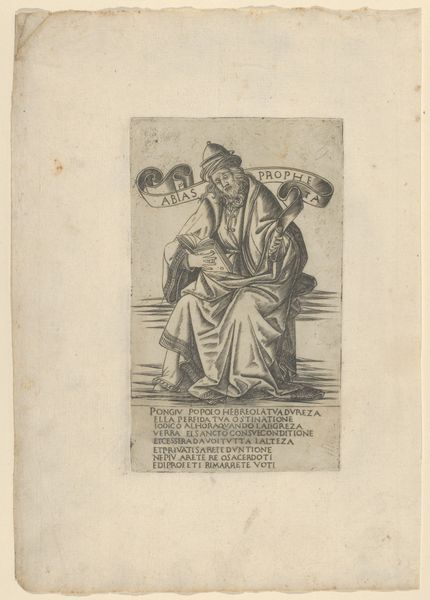

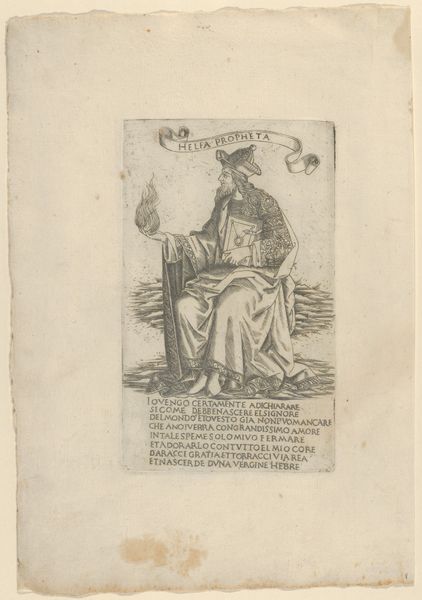

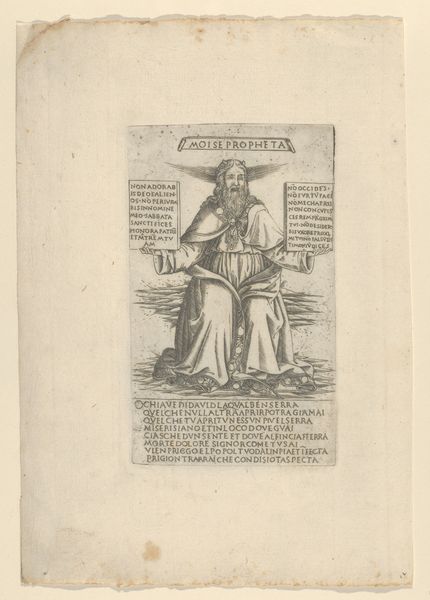

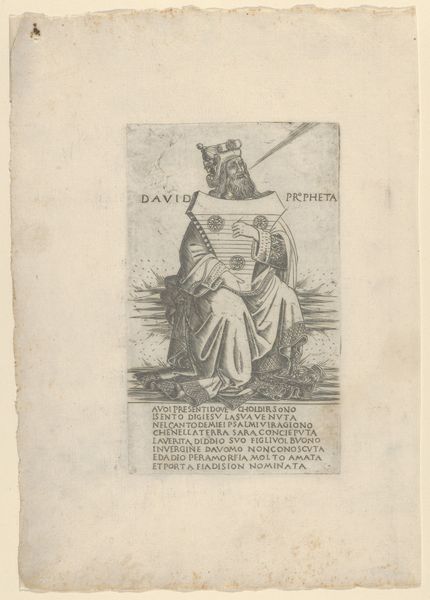

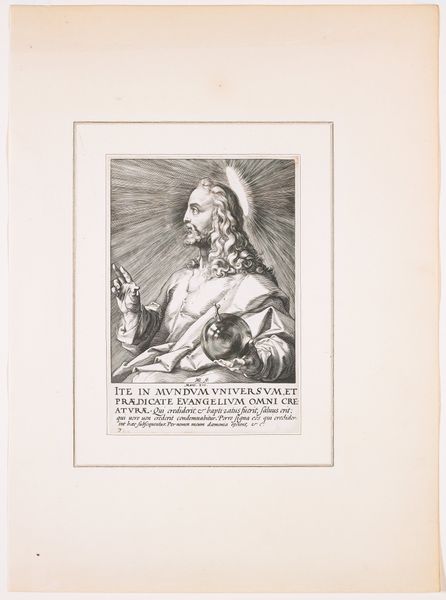

The Prophet Amos, from Prophets and Sibyls 1480 - 1490

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

medieval

# print

#

prophet

#

men

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 11 7/16 × 8 in. (29 × 20.3 cm) Plate: 7 × 4 1/8 in. (17.8 × 10.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: I see a certain stoicism radiating from this figure, almost world-weariness etched onto his face. The intricate linework, all in monochrome, adds a feeling of gravity. Editor: That’s quite apt. What you are responding to is Francesco Rosselli’s “The Prophet Amos, from Prophets and Sibyls,” dating back to the late 15th century. You can find this engraving now at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. He looks like he has seen and felt more than a man should. Curator: Indeed, the artist manages to convey such depth of emotion with what appears to be such a simple medium, just engravings, right? The textures of his beard and robe are strikingly tactile. I also notice he has some Italian script inscribed. What does it read? Editor: Yes, Rosselli captured so much emotion with the printmaking technique, popular during the northern-renaissance era. Now, if we analyze this print more deeply, we can start by recognizing the ways religious identity became heavily policed during this time in order to protect Papal Power. The Italian inscription that accompanies his prophetic declaration is translated, roughly, into "The Divine Origin with Terrestrial and Celestial Leadership…” the following passages address divine omnipresence over life and death, good versus bad. The politics of the image is heavily inscribed onto its symbolic and linguistic power! Curator: It does deepen the piece, realizing what was circulating in culture while it was produced, but even without it I can connect to it! Amos looks tired, like someone weighed down by delivering difficult truths. He isn't romanticized; he is real, fallible, the every-man who gets handed a divine task that no one wants. Do you agree, Editor, that it’s hard not to see some part of yourself reflected in the prophet’s countenance, perhaps questioning one's beliefs while holding onto truth? Editor: From a modern secularized viewpoint, it is difficult to conceptualize a man speaking God’s message…however, it is easy to read it, like a political campaign being waged at all levels! The propaganda power, and the symbolism within each representation and dissemination across early print, holds an important position. This political interpretation can extend, even, to include considerations about how institutions display such works today, who owns these images and why! Curator: Very valid questions to consider, particularly now! For me, though, it brings me back to those deeply personal connections we feel with images. The universal resonance with such stories continues through centuries, regardless of their purpose. Editor: Yes, and to continue exploring those interconnections provides an expansive insight to historical, artistic, and cultural heritage for both you and me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.