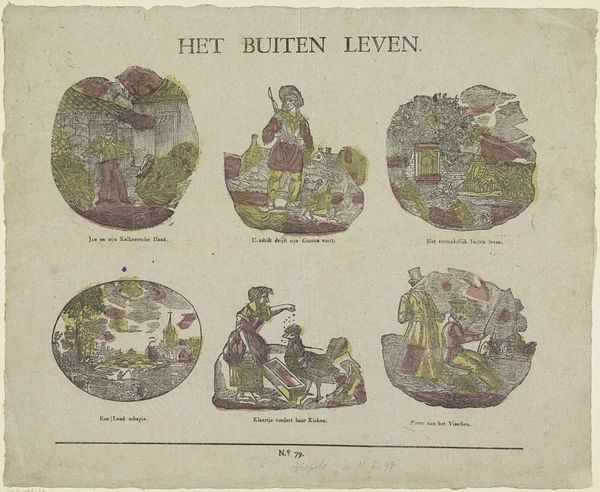

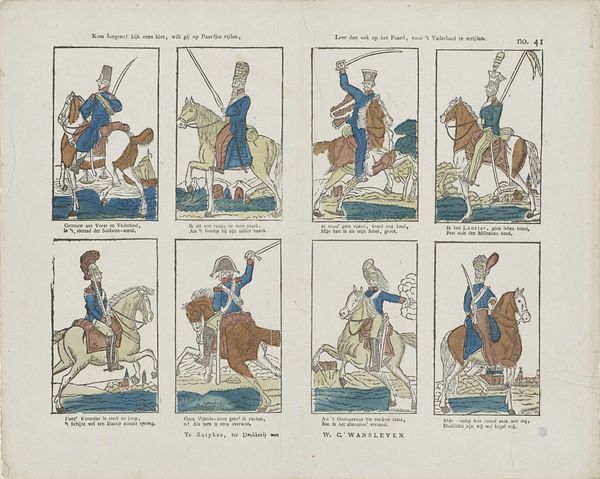

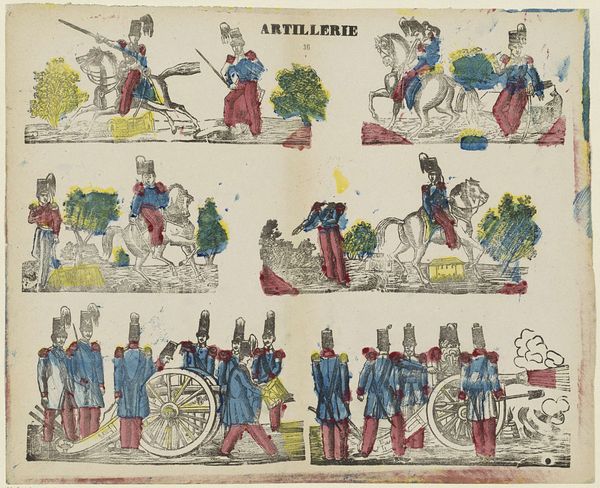

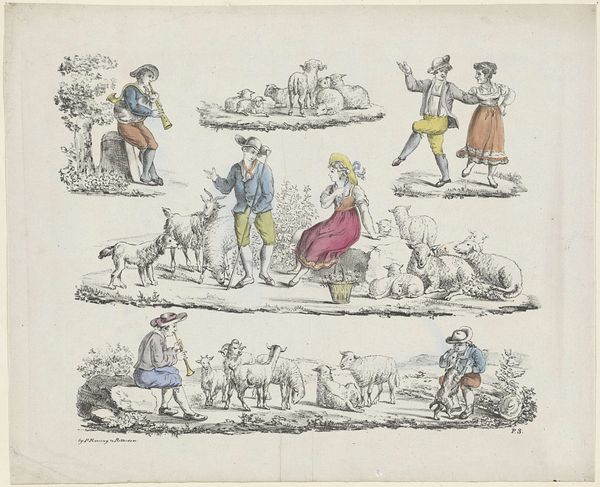

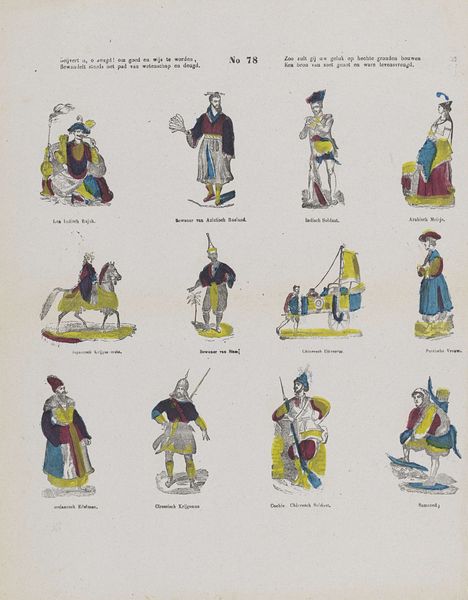

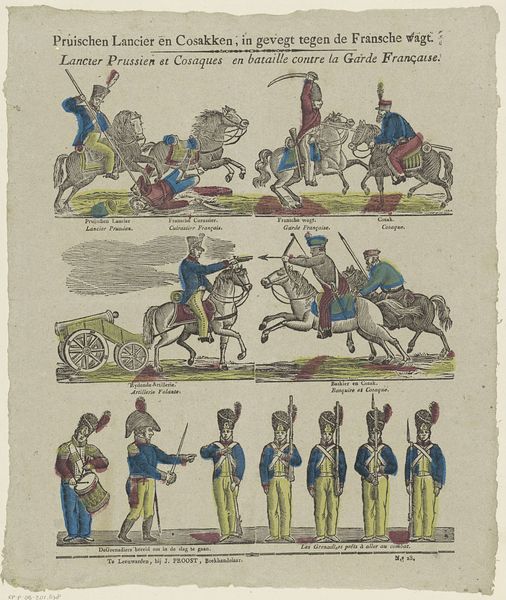

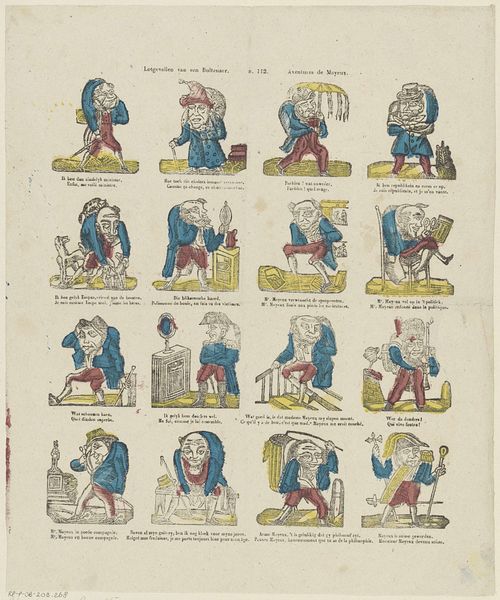

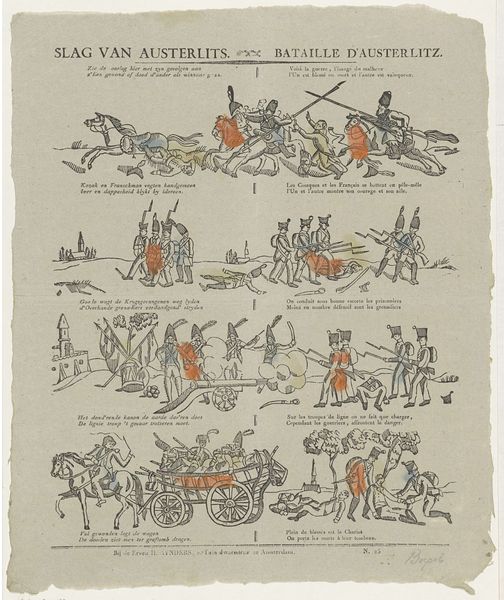

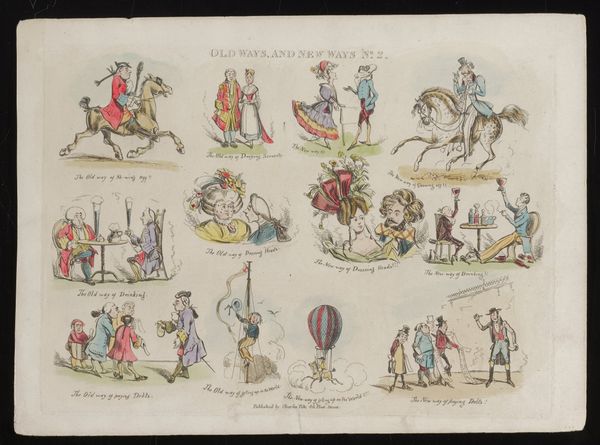

drawing, print

#

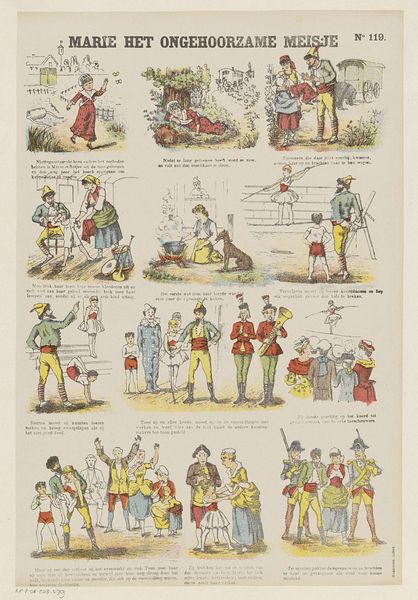

drawing

#

quirky illustration

#

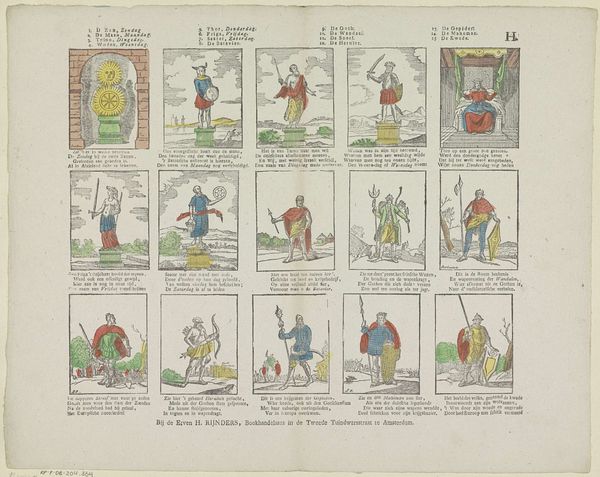

blue ink drawing

#

childish illustration

#

cartoon like

# print

#

caricature

#

personal sketchbook

#

folk-art

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

cartoon style

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

cartoon carciture

#

sketchbook art

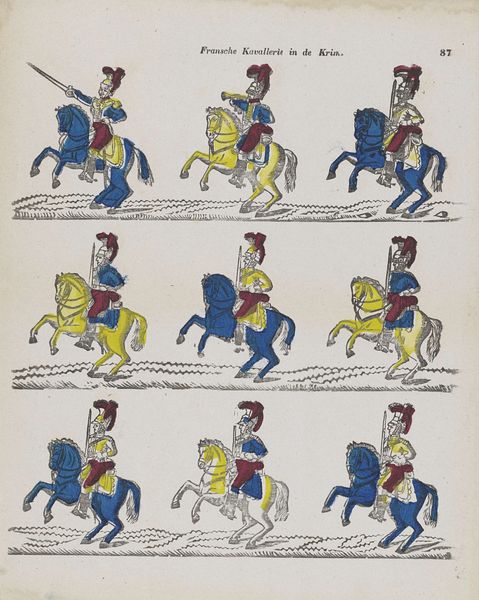

Dimensions: height 328 mm, width 407 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

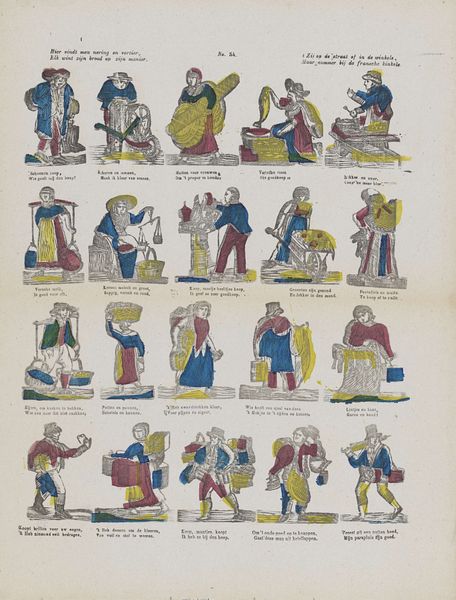

Editor: This is "Het roverleven" by Philippus Jacobus Brepols, made sometime between 1800 and 1833. It’s currently at the Rijksmuseum, and it looks like a print with some drawing involved. The figures have a sort of folk-art style, but I'm curious what stands out to you? Curator: Well, I'm immediately drawn to the materiality of this print. Consider the context: early 19th century. Printing wasn’t as streamlined as today. This piece involves some degree of manual labor at every stage, from the preparation of the printing blocks to the eventual hand-coloring we see. The relatively simple color scheme speaks to that as well. Editor: So you're focusing on how it was physically made? Curator: Exactly. And what that suggests about its consumption. Was this aimed at a wealthier patron, who could afford more elaborate, colorful prints? Or a wider audience? The deliberate naivete, almost cartoonish, feels like a vernacular aesthetic meant for broader consumption, not some elite collector. What do you think about the images presented here? How do they connect to that same concept? Editor: I notice the short scenes are labeled; "In the Dungeon," "In his camp", and so on, suggesting some narrative being sold along with the imagery. The simple construction would mean they can make and sell more! Curator: Precisely. It's about accessing a market, distributing a story. That this folk-art aesthetic comes into being at the very moment industrial printing processes begin emerging tells us something critical about cultural production at the turn of the century, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Definitely! I hadn’t thought about how industrial production could have spurred a counter-movement in handmade prints. It changes how I see the whole piece. Curator: Material realities always leave their traces. Being attentive to process unlocks so much.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.