Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

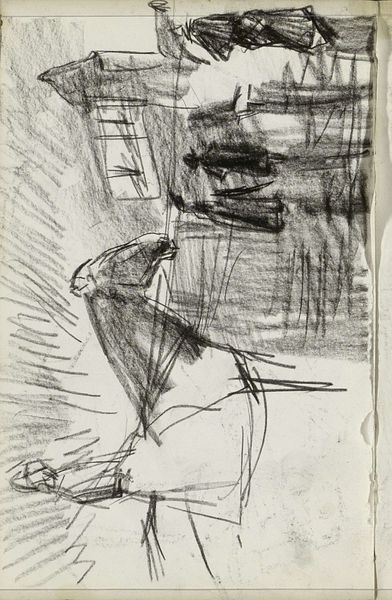

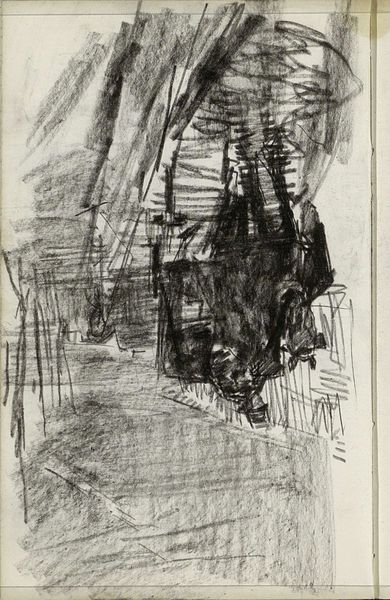

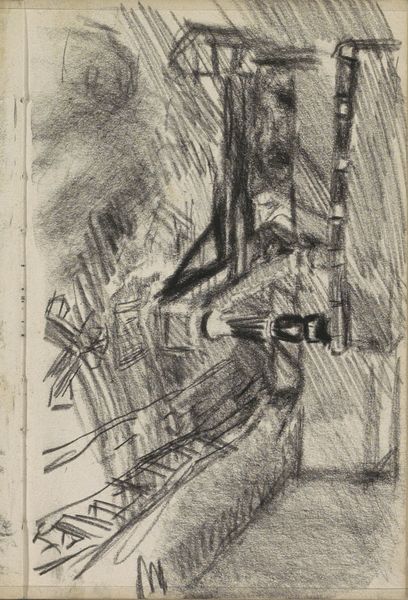

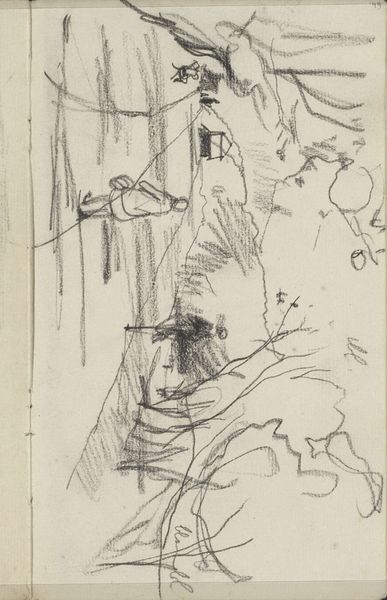

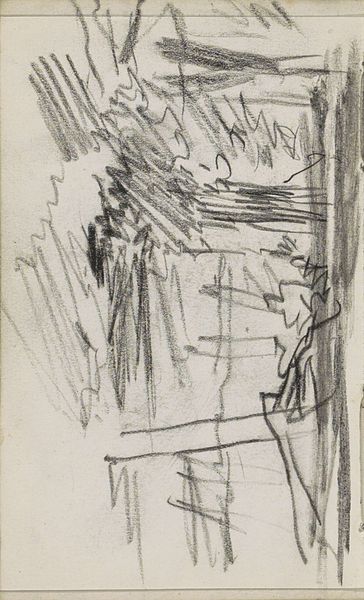

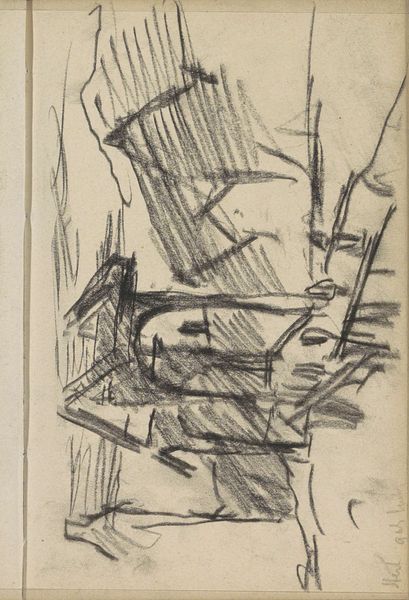

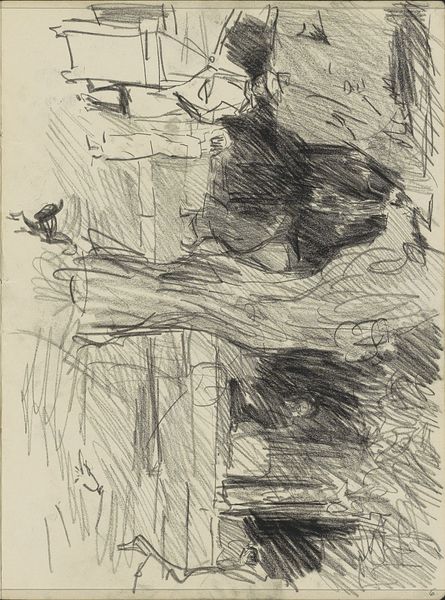

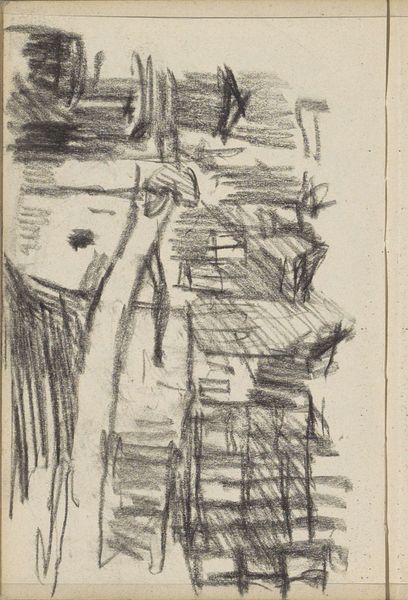

Curator: Before us hangs Isaac Israels' "Ruiter," created sometime between 1875 and 1934. It's a graphite and pen drawing currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you initially? Editor: It feels spontaneous, almost frenetic. There's a real sense of movement, even though it’s just a quick sketch. I wonder who this rider is and where they're going. There is also an uneasiness because, for example, I can’t decide what the box behind the horse rider may contain. Is it another cart with merchandise? Or even someone else riding along? Curator: Israels was known for his impressionistic style. His approach emphasized capturing fleeting moments, which explains the sketch-like quality you perceive. The interesting thing is how it speaks to a wider phenomenon within Impressionism. With industrialisation came mass consumption of commodities that were affordable even for the rising middle class. It has been theorised that many Impressionists took that up into their artwork – thus focusing less on any deeper meaning. Editor: So, it’s more about the aesthetic appeal and less about representing a narrative or social critique? But, of course, nothing exists in a vacuum. Wouldn't portraying the rise of mass consumption still constitute social commentary, albeit subtle? And if this work speaks of accessibility, why isn’t everyone depicted the same, equal way? Curator: Well, Israels frequently depicted scenes from everyday life in Amsterdam, from the wealthy merchants on their steeds to women working at the docks, or just in a normal intimate setting. The fact he decided to give those scenes such high status elevates people that are hardly given a platform to shine. And for many impressionist and realist artists, this elevation to equality has been one of the main missions to their creations. Editor: I appreciate that viewpoint; considering his focus on ordinary individuals humanizes subjects and offers a slice of social history from the margins to the cultural central stages. It challenges a very conservative vision. Perhaps my unease stemmed from how easily such works can be misinterpreted within a capitalist framing, as celebrating the status quo rather than critiquing it. Curator: Absolutely. The ambiguity is part of what makes Israels’s works perpetually engaging. His subjects force us to consider our perceptions. Editor: Well, looking again with this background, I realize I came at the work with some unfair prejudices and preconceptions about art from that period. Israels opens a doorway.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.