# print

#

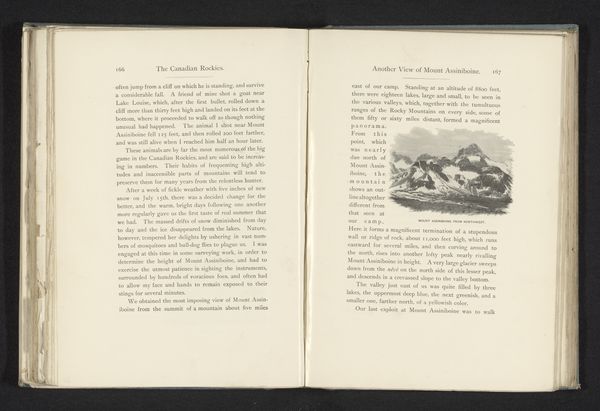

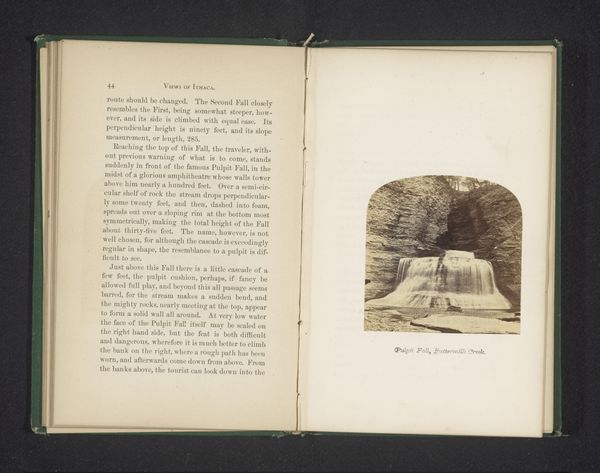

landscape

#

waterfall

Dimensions: height 121 mm, width 86 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This image presents “Waterval te Leanchoil,” a print created before 1897 by Walter Dwight Wilcox. Looking at the falls nestled amongst evergreens, what strikes you most initially? Editor: A quietude, paradoxically. There's a stark stillness within this depiction of rushing water; almost like a captured moment of colonial tranquility amid displacement and disruption. The high contrast and detail feel very precise and intentional, yet it also brings forth a tension given the wider context. Curator: You pick up on the nuance between stillness and rush. That’s interesting in relation to the broader socio-political circumstances of art production during the late 19th century and how landscapes were often used to reinforce national identity, gender, and race. Wilcox, here, provides an unpeopled vista – save, arguably, the faint, implied trace of industry or settlement with that station so prominently alluded to. Does it suggest ownership or exploitation of the natural world? Editor: Exactly. Consider also how landscape paintings often functioned as claims of territory, mirroring colonial projects of mapping and possessing lands. Is Wilcox participating in that rhetoric or critiquing it by depicting a seemingly untouched, romantic scene alongside clear reference to modern colonial incursion? Where does he stand ideologically in light of western expansion? Curator: It's important to understand the role prints like these played in circulating idealized, constructed images of wilderness to broader audiences. Was it an attempt to preserve a fading reality or perhaps to mask the ongoing violence against indigenous peoples and ecological transformation? Editor: The absence of indigenous peoples or explicit markers of social strife reinforces this feeling that colonial narratives often seek to sanitize and erase the darker, less picturesque aspects of settlement. The strategic emphasis on sublime nature acts to cover this ideological manoeuvre. I am left contemplating the ethics involved in viewing this image then and now, particularly acknowledging that my interpretation will not always coincide with Indigenous readings and memories. Curator: Those are very valid points to keep at the forefront of our considerations, I find my mind lingering specifically on the name itself - and the colonial legacy there. It invites some pointed questions around whose voices have been and continue to be centered in that region. Thank you for this vital critique. Editor: Indeed, by juxtaposing aesthetics, materiality and the latent socio-political undertones of art historical contexts we invite more honest discussion, thus enriching, and critically expanding, the field.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.