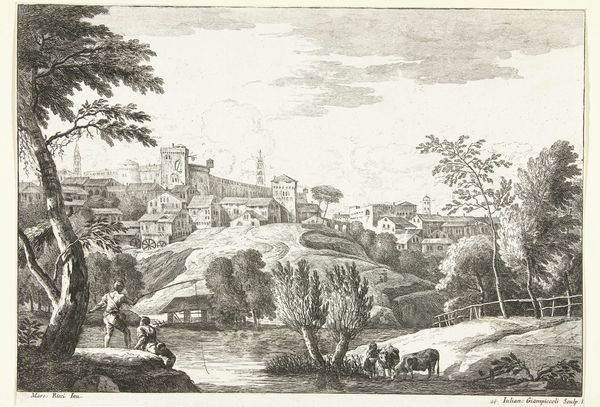

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 137 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The work before us is a print called "Vergezicht met herder te paard", created by Frédéric Théodore Faber in 1831. The artist utilized the engraving technique, giving the artwork a remarkable level of detail. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It’s instantly peaceful, wouldn’t you say? The composition, though realistic, almost feels like a stage setting. A bit dreamlike. I find my eye keeps returning to that distant structure on the hill; it draws me in, like a forgotten watchtower. Curator: The landscape itself is crucial here. Landscape art became a way to assert national identity and pride, especially in the wake of the Napoleonic era. Faber’s scene may well reflect the period's desire to establish a connection with the Dutch countryside and to locate within it a national sentiment. Editor: The shepherd, then, could be interpreted not just as a figure in the landscape, but as a symbol of the people, connected to the land, maybe a romantic figure representing the 'common' identity of the nation. The sheep suggest traditional livelihoods and a connection to the land's bounty. The building on the hill, a beacon? A protective element, of sorts. Curator: Absolutely. The placement of the watchtower-like structure on the hill does suggest defense and surveillance. These visual markers often communicated power and control, very much intertwined with the narrative of nation-building through images that circulated in prints at that time. Prints like this offered wider circulation to such imagery. Editor: There's a simplicity, though, in the way Faber presents it all. Not grand, not imposing – a simple country scene, yes. Yet the careful lines, and shading – Faber highlights something significant. It is as if the shepherd represents not authority, but an inherent unity. It also gives us a strong sense of time in passing – how culture forms our identities gradually as generations slowly shift from age to age. Curator: An excellent point. The enduring appeal and purpose of such works lies not just in aesthetic quality or nationalistic intent, but its connection to memory – it carries visual reminders of an older order and gives value to that historical memory for an emerging nation-state. Editor: Thinking about Faber’s image, its symbolism suggests how a shared visual vocabulary could build the narrative of a people over time. Curator: It becomes evident how this unassuming pastoral print offers insights into the socio-political constructions of 19th-century Netherlands, shaped by identity formation and heritage concerns.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.