drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

medieval

# print

#

etching

#

etching

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 129 mm, width 217 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

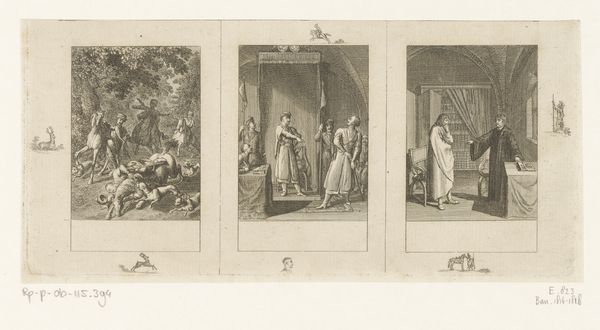

Curator: This delicate etching by Charles Onghena, titled "Bladelin-altaar van Middelburg," was created in 1836. It presents a fascinating glimpse into a medieval scene. Editor: My first impression is the level of detail given the medium. It feels so precise and delicate; look at how the lines define form without ever becoming harsh. Curator: Absolutely. Onghena's choice of etching revives medieval artistic traditions during the nineteenth century. This particular image references and reimagines the famous Bladelin Altarpiece, highlighting the value that contemporary audiences saw in Early Netherlandish painting. We might consider how its reproduction in print democratized access to important artistic narratives. Editor: Considering Onghena's methods here, what materials would he have needed, what would this etching plate have been made of? It has an ethereal feel—so unlike other reproductive prints using steel and mass manufacturing methods—but so much work in the execution. Curator: The choice to depict a religious scene certainly played a role in the painting's appeal. These images weren't simply aesthetic objects but were intricately tied to systems of power and moral authority—historical dramas serving social messaging, displayed for various viewers. Editor: Seeing it reproduced here gives me pause. An etching softens the image, losing the sharp lines of the original and maybe something of its power. I’m intrigued by that act of translation and its implications for understanding labor and consumption, for how art becomes both an object of contemplation and an item of commerce. Curator: That’s well put. By circulating this etching, Onghena contributes to a conversation about cultural heritage and artistic legacies. We see art functioning in multiple ways – as a symbol of prestige, a moral lesson, and a source of artistic inspiration, available even as a modest printed artwork. Editor: Exactly, and these various functions of image making are dependent on distribution. The networks which supported them show us something interesting about its consumption. Curator: A superb perspective to consider—thank you. Editor: It’s been a pleasure to explore its texture and wider cultural meanings together.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.