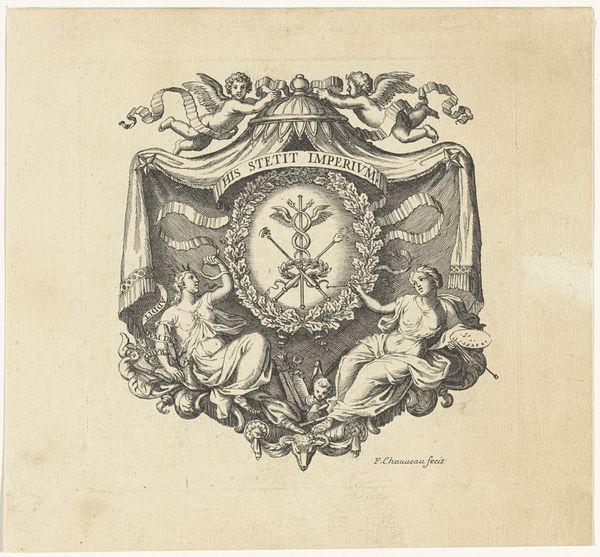

Ornament: Monogram voor Christus 'IHS' , opgebouwd uit de passiewerktuigen 1608 - 1630

Dimensions: height 224 mm, width 254 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this piece, it evokes a certain somber quality, doesn't it? There's a density to the composition, a heaviness almost, with all the symbolic elements packed tightly together. It feels more like a coded message than a celebratory image. What do you make of it? Editor: Well, what we have here is a print, most likely an engraving, dating from somewhere between 1608 and 1630. It's titled "Ornament: Monogram voor Christus 'IHS', opgebouwd uit de passiewerktuigen" by Michael Snijders, and it is a visual encapsulation of Christian suffering and redemption. That feeling you’re picking up isn’t accidental. Curator: Absolutely, but I’m immediately drawn to its somewhat morbid symbolism. Those "passiewerktuigen"—the instruments of Christ’s Passion—are assembled to form the IHS monogram. You see the cross, the crown of thorns... It's quite the collection of painful symbols. Is it supposed to inspire reverence or something else? Editor: It is complex. This was produced in a period of intense religious conflict, when symbols were used to both inspire and enforce social norms. It wasn’t simply about reverence; it was about reinforcing power structures and moral codes within a deeply religious society. The depiction is overtly Catholic and emphasizes penitence. The instruments of torture themselves form the sacred name—it is quite literally weaponizing belief. Curator: That is really thought provoking. Thinking about the placement, who would have interacted with it? How accessible would something like this have been? Editor: These prints, precisely because they could be reproduced and disseminated, often served didactic functions. Placed in a private chapel, maybe a personal study. Also consider that literacy wasn't universal then, and images like these played a crucial role in communicating complex religious ideas to a broader audience. They were pedagogical tools but they also played a key part in broader propagandistic campaigns. Curator: It’s interesting how something that seems purely devotional can also function as a potent political statement. There's so much intention in this one piece. I initially only sensed an artistic experience. Now it almost feels like a chilling meditation on power and devotion! Editor: Precisely! The power of art lies in these layers of meaning. Snijders isn’t just showing us a monogram; he's giving us a carefully constructed argument about faith, suffering, and the societal frameworks in which these are given meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.