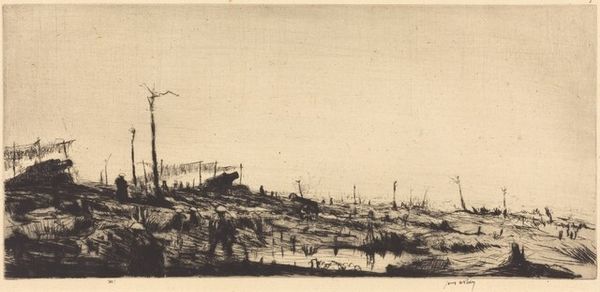

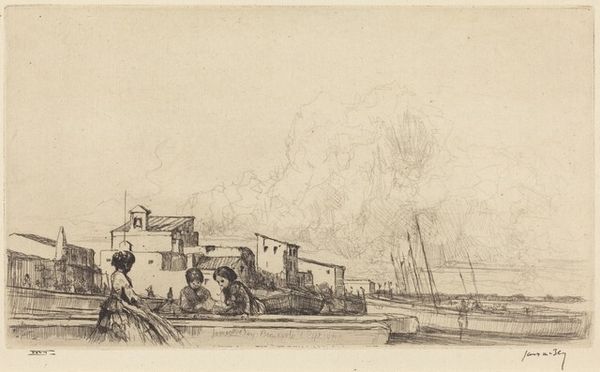

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

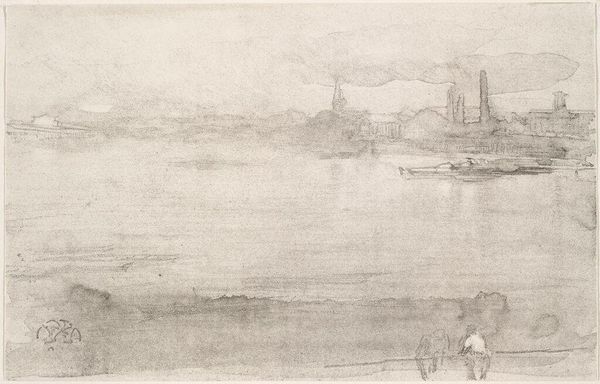

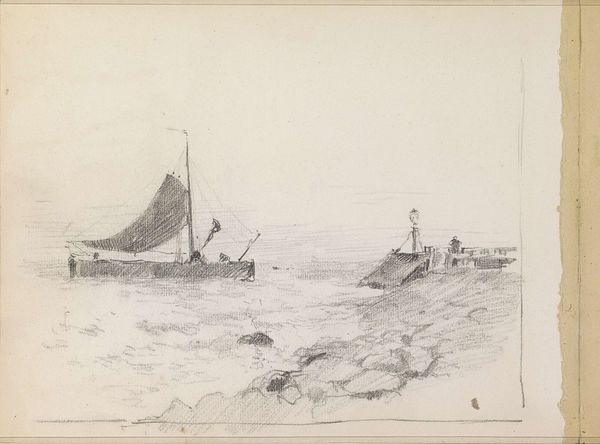

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

ink

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

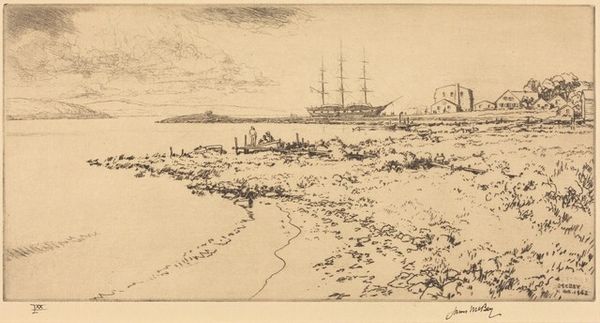

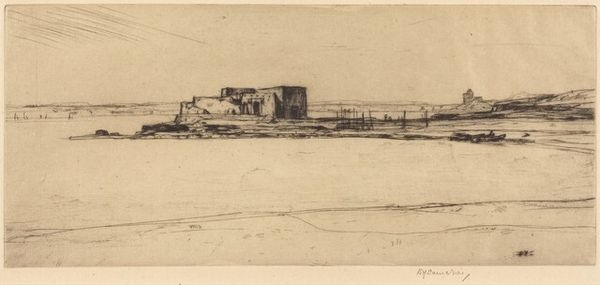

Editor: So, here we have James McBey’s "Morning, Catterline," an etching made in 1909. It’s a detailed coastal scene… There are figures on what appears to be a pier, with boats scattered around the water. The scene is quite subdued; I get a sense of the everyday life of a fishing community. How do you interpret this work? Art Historian: Thanks for sharing your initial impression. Immediately, the work conjures thoughts about labour, specifically how landscape becomes inextricably linked to labour and livelihoods. Looking at Catterline, we should be asking: who are these figures occupying the pier? And whose stories are excluded from the romanticised landscapes? Editor: That's a perspective I hadn't considered! It's easy to get caught up in the aesthetic and miss those stories. So the artist, as a man, had a specific point of view. How does this shape what we see, or don't see, in the landscape? Art Historian: Precisely. Consider McBey's position within the context of early 20th-century Scottish art. He romanticizes, yes, but what realities are obfuscated? We should also explore the political economy of fishing in Scotland at the time and the experiences of women, children and migrant workers. Editor: I never thought of landscapes this way, they always just seemed, well, pretty. But this opens up a whole new avenue for analysing art and society together. Thank you! Art Historian: And thank you! Because understanding landscapes as political projects and never as simply, “pretty”, provides the pathway for future interrogation, as well as the inspiration for further, necessary disruption.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.