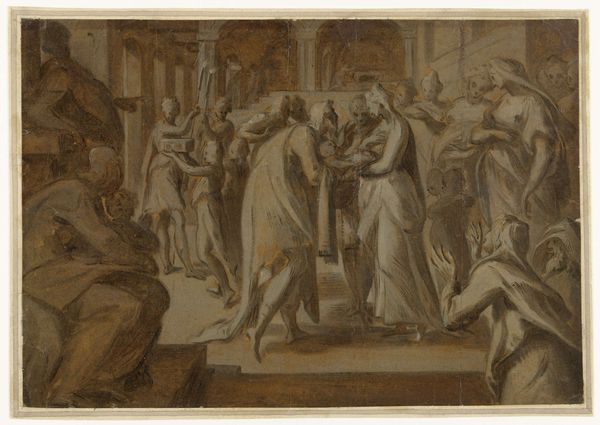

Diana bittet ihren Bruder Apollo, sie für den durch Niobe erlittenen Hohn zu rächen, aus dem verlorenen Niobidenfries an der Fassade des Palazzo Milesi in Rom 1656

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink, pencil, charcoal

#

drawing

#

high-renaissance

#

baroque

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

14_17th-century

#

watercolour illustration

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This compelling drawing is by Polidoro da Caravaggio, crafted around 1656. It's rendered in pencil, ink and charcoal on paper and illustrates Diana pleading with Apollo to avenge the insult suffered by Niobe. Editor: My first impression is how haunting the figures appear, almost like faded memories emerging from the paper. The monochrome palette gives it an ancient, otherworldly feel. Curator: Absolutely. Caravaggio created this drawing as a study for a fresco on the Palazzo Milesi facade. It offers a fascinating glimpse into how public art operated during the Baroque era. Consider the very public display of this mythological scene and what its message might have been. Editor: Revenge narratives often speak to deeper issues of power, hubris, and social standing. In a patriarchal society like the one Caravaggio lived in, female honor was paramount, making Diana’s quest all the more pertinent. Is it not true that Baroque art frequently served as visual propaganda, reinforcing social norms through dramatic storytelling? Curator: Certainly. The Palazzo Milesi was, after all, a prominent location. Visual narratives acted as affirmations of family standing and were, at times, deliberate lessons about acceptable behaviors. Revenge was a recurring motif and the consequences of disrespect, made vividly plain here by the artist. Editor: The composition, though a study, still reflects an interesting intersection of violence and vulnerability. Diana's gesture of request has a certain tenderness, while Apollo, bow in hand, embodies fierce retribution. The original fresco must have created a profound emotional impact on passersby. Curator: Precisely, and the interplay of these elements tells us about the sensibilities of the period. It's a stark reminder of the public role art played in shaping social discourse and bolstering the status quo. Editor: Considering the modern audience, contemplating issues of representation, and gender-related imbalances reflected in historical narratives becomes vital. Looking at how ancient tales were reworked to buttress cultural concepts—it invites crucial questions concerning our own relationship with historical constructs. Curator: Indeed, studying works like Caravaggio's helps us unravel the intricate web of art, power, and social dynamics throughout history. It allows a unique perspective on cultural values which framed its genesis and eventual reception. Editor: This glimpse behind the scenes of a grand fresco makes me aware of how narratives get told, modified and wielded in diverse times. It's as though the echoes of that long-ago vengeance request resonate even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.